Dave Chappelle's new YouTube comedy special 8:46 is a masterpiece.

The 27-minute monologue's title refers to the length of time former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin pushed his knee against George Floyd’s neck, leading to his death on May 25 and provides a searing explainer of how the event triggered the racial protests engulfing the US and other parts of the world.

Weaving history, politics, personal experiences and thoughts on rapper Ja Rule, Chappelle paints a picture of a US at a reckoning with its history of discrimination against its African-American citizens.

The comedian, who traces his own slave ancestry in the set, doesn’t provide solutions for the current social malaise.

That’s not his job, he says, as “the streets are talking for themselves.”

Instead, what he offers is his role as a stand-up comedian, which, in these torrid times, is to be a facilitator and conduit for difficult conversations.

While 8:46 is rightfully hailed for its intense and sweeping analysis, it should also be celebrated as a seminal defence of a subversive art form that has historically allowed a range of black voices to be heard.

Chappelle joins an esteemed lineage of over centuries worth of comics who often used humour to both inspire and, in many cases, sugar coat the bitter realities experienced by a historically disenfranchised community.

Early beginnings in the 16th century

While there is no clear genesis to the roots of African-American comedy, author and comic Darryl Littleton traces some of its past back to the slavery era of the US, stretching from its founding in 1776 until its formal abolishment in 1865.

In an interview with broadcaster NPR, promoting his 2007 book Black Comedians on Black Comedy: How African-Americans Taught Us to Laugh, Littleton goes on to state that some of the first examples of showmanship goes back to performances of slaves in their after hours – a format he described as the prelude for the minstrel era shows of the 19th century.

It was the performers who had the last laugh, however. Littleton said the bosses in the audience didn’t catch on to how the exaggerated caricatures of themselves was essentially a form of trolling.

"What the slaves were doing was making fun of the masters," Littleton described, before concurring with the NPR host Tony Cox’s follow up comments that in turn “the master was watching the slaves make fun of him, and so he started making fun of the slaves making fun of him.”

The first lady of African-American comedy: Moms Mabley

With the emergence of stand-up comedy in a segregated US in 1930s and 1940s, African-American talents began emerging out of the Chitlin' Circuit, a string of performance venues stretching the east, south and Midwest that caters for black audiences.

It was there that the first lady of African-American comedy was born. A veteran of the circuit, Moms Mabley built a trail-blazing career in film and stage, which included being the first female to headline Harlem's Apollo Theatre in the mid-1930s.

A lot of that success is down to her shtick of being an innocent looking aunty who lets fly with raunchy and often musical observations about African-American bigotry.

This is exemplified in a bit from 1961 where she sings an anecdote, in the style of Ray Charles's Georgia, of how election officials from the state kept sending her to the back of line when attempting to cast her vote. "Their arms reach out for me, they must walk me desperately," she sings. "But if I can just break free, they would see the last of me in Georgia."

Mabley's influence is found today in the lovable and cantankerous elderly women characters seen in Tyler Perry's Aunt Media, Eddie Murphy's Nutty Professor and a series of films starring Martin Lawrence.

The wise and dirty uncle: Redd Foxx

Playing the gender counterpart of Mabley was Redd Foxx, who won a multi-racial audience through a bawdy humour laced with off the cuff truths of the black experience in America.

In his 1978 comedy special On Location, Foxx took on the "go back to Africa" insult that was standard in the US at the time.

"Back to Africa? Who? I ain’t never been to Africa. If you send me home, send me to St Louis, Missouri,” he quipped. “What would I do in Africa, standing in the jungle, with a $750 suit and alligator shoes?"

The funny professor: Dick Gregory

However, some comics also wanted to try another approach to tackling racism. It was Dick Gregory who harnessed comedy as a means to educate. He used humour to point the sheer absurdities of US race relations.

That approach resulted in his career breakthrough in 1961, when entertainment mogul Hugh Hefner reportedly spotted a particularly set to an all-white audience at Chicago's Roberts Shaw Bar.

On stage, Gregory recalled an experience of entering a restaurant in the south for a meal. As he was about to dig into his chicken, Gregory recalled being confronted by angry customers.

“These three white boys came up to me and said, 'Boy, we're giving you fair warning. Anything you do to that chicken, we're gonna do to you,'" he said. “So I put down my knife and fork, I picked up that chicken and I kissed it. Then I said, 'Line up, boys'."

Excited by the talent and audacity, Hefner immediately hired Gregory to work at his venues which in turn set up an influential career on stage and as a civil rights activist.

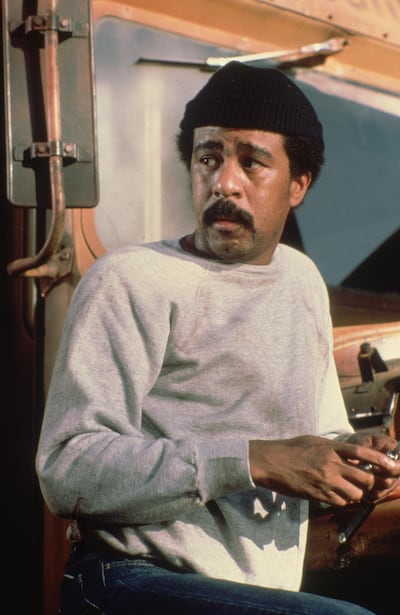

The tragedian: Richard Pryor

While those before examined systematic discrimination through a detached and observational lens, it was Richard Pryor who brought home some of its horrors.

And that’s down to Pryor being one of the first comics to really blend comedy with the tragedies of everyday life as a black American. Instead of brushing away some of the injustices with the curt punchline, Pryor fiercely leaned into his experience with the audience forced to uncomfortably sit through material that was nothing short of harrowing.

In his classic Grammy award-winning album, 1974's That (N word) is Crazy, Pryor lays bare the dehumanisation that comes with constant racial profiling. In a particularly disturbing moment, he recalls being stopped by a police officer and urging him not to shoot as he reaches "out for my pocket for my licence."

It is hard to listen to this bit now without thinking of Philando Castile, killed in front of his partner and child in his car by a Minnesota police officer during a traffic stop.

Stand-up comedy as the last bastion of civil discourse

While Eddie Murphy has long been viewed as the heir to Pryor, his decision to leave comedy (after two classic comedy specials 1983's Delirious and 1987's Raw) for a career in the movies, it meant Pryor's legacy of caustic societal observations skipped a few generations, only to land on the shoulders of modern comics including Chappelle, Chris Rock and Wanda Sykes.

With a truly integrated and social media savvy crowd now in the audience, the material took on a more journalistic bent.

Rock’s material, in particular, is often inspired by the present state of race relations. In 2016, he delivered a withering opening monologue at the Oscar ceremony that decried Hollywood’s tokenistic treatment of black talent, some of which boycotted the ceremony. "If you want more black people at the Oscars just have black categories like Best Black Friend," he said.

While in his latest 2018 Netflix special Tambourine, he delivers, perhaps, the most incisive pun to describe the situation we are in today.

"Whenever the cops gun down an innocent black man, they always say the same thing, ‘Well it’s not most cops, it just a few bad apples.' I had a bad apple, but it didn't choke me out ... I know it’s hard being a cop. I know it’s dangerous, but some jobs can't have bad apples," he said.

In a frighteningly polarised US society, Chappelle concludes 8.46 with the ominous warning that his art form is the last bastion of discourse in a nation on the edge of civil breakdown, "because after this, it is just ra-tat-tat-tat."

The fact that these tales and experiences of discrimination and injustice continues to be heard from stages over a century later not only points to the slow pace of racial relations in the US, but it also cements the important role stand-up comedy has always played in opening people’s eyes to present state of the world.

And that’s no laughing matter.