The racial reckoning spawned by the Black Lives Matter movement will soon be reflected in British school books.

The UK's Department of Education will expand its music curriculum for children aged 5 to 14 to include underrepresented voices in rock 'n' roll, jazz and classical music, according to The Sunday Times.

When it comes to the first two genres, even today’s digital natives will be familiar with the analogue sounds of Little Richard, dubbed the "architect of rock 'n' roll", and the jazz songbird Nina Simone.

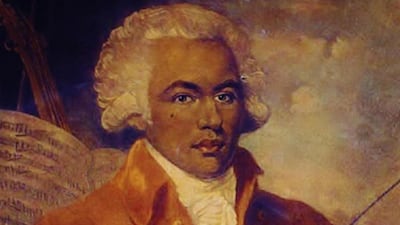

However, some may scratch their heads when it comes to the name Joseph Bologne.

The 18th-century French-African composer, also known as Chevalier de Saint-Georges, may not be a marquee name in concert halls today, but his pioneering life on and off the stage helped redefine the violin concerto, as well as expose some of the racial fault lines coursing through even France’s most liberal circles.

Hailed as "the black Mozart", Bologne's life is also set for the big-screen treatment next year, with Killing Eve writer Emerald Fennell reportedly behind a biopic that will celebrate his cultural contributions, from his invigorating compositions to his influence on Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

While excited at the prospect of a new generation discovering his work, Ronald Perlwitz, music programme head for the Department of Culture and Tourism – Abu Dhabi, is cautious of the inferences made from Bologne’s moniker.

“To call him the black Mozart ultimately diminishes his work. If he is the black Mozart, then Mozart should be the white Joseph Bologne,” he says.

“What Joseph achieved was so much that music is only part of it.”

The Lionel Messi of 18th-century France

Indeed, students should have fun digging into the life of Bologne. It is, in part, a swashbuckling tale as he was not only a leading composer, but a champion fencer and a socialite with friends in high places, including French queen Marie Antoinette.

In many ways, Perlwitz explains, Bologne was a man of his times.

“His life embodied the qualities and values of 18th-century France,” he says. "This was the time of Enlightenment, when the idea of human existence was universality. It was not just about finding one skill, being good at it and that's it. It was about experience and trying everything. It was about living a full life."

Born on Christmas Day in 1745 on the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, Bologne was the child of an enslaved Senegalese woman and a French aristocratic plantation owner.

Despite the scandalous nature of his arrival, Bologne had a close relationship with his father and went on to receive a stellar education in France.

“This is what makes him such a fascinating character already, because his life was this social mix of high and low,” Perlwitz says.

“On one hand, he was born to a parent that was essentially a slave, but his father, who was a rich and powerful man, never thought about it in that way and loved him very much. He went on to live the life of an aristocrat despite not being the same as some people in that circle.”

Perlwitz believes that was behind the decision for Bologne to learn fencing as well as the violin from a young age.

“This was the time of the duel,” he says. “It was through fencing that scores and disrespect were settled. Because of his background, I felt that maybe his father wanted Bologne to learn how to defend himself early.”

His skill also made him a nationwide celebrity.

With fencing the popular sport of the day, Bologne went on to become a champion with records notched up for his number of victories (it is said that he only lost one match) and speed of play.

Coupled with his growing acclaim as a violinist and composer, Perlwitz explains his appeal at the time was all-encompassing.

“Think of it this way,” he says. “It is like Lionel Messi also being a massive composer. Imagine he would play a match one day and then lead the Berlin Philharmonic the next evening. It’s kind of crazy if you think about it.”

A master and mentor

More than his sporting prowess, it was Bologne’s music that was destined to become his lasting legacy.

As an accomplished violinist, he made his performance debut as a soloist in 1772 at the age of 27 with the Le Concert des Amateurs orchestra.

The following year he became its conductor before going on to helm Le Concert Olympique in 1781, a formidable ensemble that was a favourite of Queen Marie Antoinette.

The reason for the full houses and royal audiences were Bologne’s concertos and symphonies concertantes (orchestral work with several movements), which Perlwitz describes as “rich, passionate and challenging".

“He stood in the great tradition of French violin, learnt from the greatest masters of his time, and pushed the technical limits of his instrument like no one else,” he says.

“Because Bologne was such a gifted violinist in his own right, he managed to create these beautiful and complex concertos that really elevated the instrument within the music world at the time.”

Perlwitz points to his favourite Bologne composition, 1774’s second of 14 violin concertos, as a fine example of his approach.

"It is dynamic but filled with these beautifully tender moments," he says. "Again, it is really about the violin. If you listen closely, it sounds almost velvet. It is an emotional and sensual piece of music.”

Picking up these tips along the years was a young Mozart.

Eleven years his junior, the virtuoso was an admirer of Bologne and, for a few months in 1778, they shared the same Paris residence.

A lot has been written on the relationship between the pair, with some historians arguing that Mozart went as far as plagiarising parts of Bologne’s work.

Perlwitz is not fully convinced of this theory, claiming Mozart went on to fashion his own sound with Bologne being one of his influences.

“When Mozart was young, he would listen to everything and soak up these various sounds," he says. "If you ask me, 'did Bologne have an influence in Mozart's compositions?', then definitely I will say yes, but I argue that he is one of dozens of influences in Mozart's work."

The racial barrier remains

Despite the fame and acclaim, there were some barriers that remained unsurmountable, even for Bologne, who died in Paris from a long illness in 1799 at the age of 53.

A sour note in his career, Perlwitz says, came towards the later stages of his life, when he was offered the role of heading the prestigious Academie Royale de Musique, now called the Paris Opera.

"The offer was eventually taken away because, despite the appointment coming from Marie Antoinette, who was also his backer, there were too many singers and musicians within the academy who said they would not accept orders from a person of colour," he says.

"This was one of his biggest setbacks in a career that had many achievements."

With so much ground to cover, Perlwitz is interested to see how the upcoming biopic will tackle the life of Bologne and his journey from the fields of Guadeloupe to the heart of French society.

As one of the curators of Abu Dhabi Classics, he also hopes to do his part by organising a festival performance celebrating Bologne’s work.

“It is definitely something that we are looking at,” he says. “His work is revered by the most important violinists today. Bologne’s life and music remains important.”