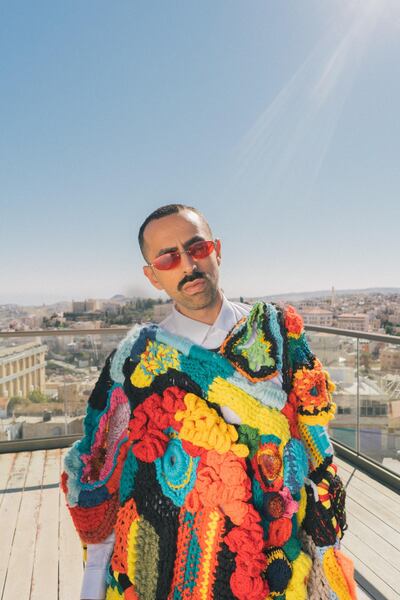

Bashar Murad describes his music as reaction to reality.

On that score, the Palestinian singer, 28, had a lot of material to play with over the last four years.

Out today, his debut EP Maskhara is a collection of four songs composed over as many tumultuous years.

It was a period that saw him record the fiery pro-Palestinian anthem Klefi /Samed.

A collaboration with Icelandic metal band, Hatari, the acclaimed track – which is not on the EP – served as a global showcase for Murad’s talent.

That profile further heightened when Coldplay enlisted Murad that year to contribute to Orphans, a track from their regionally inspired album Everyday Life.

Last month, Murad joined fellow Palestinians to protest against Israeli troops in his home neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah.

"It is really no surprise to me the songs on Maskhara all have this theme of escape," Murad tells The National.

“These songs were written during crazy times and the pandemic. While some of the moments have been positive, there are definitely messages in the songs about wanting to get away or at least feel disconnected from reality.”

New form of resistance

That said, Maskhara is no dour lament on the Palestinian struggle.

The songs bristle with energy as Bashar expands the notions of what resistance is.

It can't be all protests and picket lines, Murad sings in the pulsating Intifada on the Dance Floor, sometimes art can pack a punch just as powerful.

“And this is what I am talking about when it comes to escape,” he says.

“It’s not just the Israeli occupation, but the mental one we impose on ourselves because of the certain ideas we have.”

Born in East Jerusalem before moving into the city’s district of Sheikh Jarrah as a child, Murad grew up amid the belief that art serves more to preserve Palestinian culture than advancing the cause.

His father Said Murad is the founder of Sabreen, a revered band credited with developing the Palestinian folk song.

Last month’s flash point in Sheikh Jarrah, Murad says, put that idea to rest.

On the front lines of many of the protests, Murad says the experience confirmed the ideas explored on Intifada on the Dance Floor, written months prior, are relevant.

“Art is also a legitimate form of resistance and that was beautiful to see in the protests,” he says.

“When you are forbidden from resisting in any way, you become more creative.

“So we raised flags and balloons and the Israeli soldiers took them down. We then drew these murals on the walls and the municipality sprayed over it. And then we sang these songs despite the troops coming for us.

“While not many of us have the energy to be oppressed and attacked every day, art was a galvanising force and is the way to still keep the conversation going on what's happening.”

Resignation and resilience

Maskhara is unashamedly a pop record.

All songs are packed with memorable hooks and carried by throbbing grooves.

Then there are Murad's expressive and elastic vocals skirting between playful and mournful.

Over the bobbing synths and dance beats of Maskhara's title-track, Murad illustrates how the hedonistic Palestinian youth culture in the occupied territories are laced with resignation.

“My fate is out of my hands, no one understands my way of life,” he croons in the verse.

“But in my hand is a glass of whiskey and it still doesn’t quench me.”

While the desperation is real, Murad says the song is ultimately about resilience.

“It does sound rather cynical at first,” he says.

"But it is also about going through those dark times and finding your way to get to the other side."

That message is fully realised in the epic closer Ana Wnafsi.

Translated to “myself and I,” this is a paean reconciling the previous track’s themes of dislocation and escape.

Over club-ready beats and oud riffs provided by his father, the message here is to find your freedom through expression and self-care.

The latter is something Murad feels particularly strong about, as the mental scars of occupation can be as invisible as they are pervasive.

"It can be as equally important in some ways,” he says.

“Yes, we need to fight on and resist but we need to take care of ourselves and each other too.

“And this is also what I mean when I am talking about escape, it's not to say give up. It's about taking a break before going on to fight another day.”

Bringing it back home

That ultimate note of optimism, in addition to Maskhara's various styles, epitomises the spirit of Sheikh Jarrah.

While the world may have heard about the district only a month ago, Murad hopes his music helps sheds some light on its place as an important Palestinian hub.

"It is both a physical and cultural intersection," he says.

"It can lead you to different parts of the city but here is also where Palestinian organisations, cafes and creative places are.

“My father's band has their studio here and I grew up there with all that music and inspiration. Sheikh Jarrah will always be a part of me and what I do.