Steve Goodman describes the music he makes under the moniker Kode9 as a virus. It's a pretty persuasive idea: invoking the near-future science fiction of biological warfare that is the aesthetic analogue of his sound (discombobulating, moody electronic dance music), as well as the modish fixation with memetics - the notion that, via the internet, ideas pop up in different locations and find it easy to replicate, self-perpetuate and mutate - like viruses.

Goodman is also an academic and author specialising in theories about sound, music, technology and its military uses. His recent book, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect and the Ecology of Fear, is an intrinsically political critique, reflecting an environment in which military and consumer-capitalist innovation in the use of sound to exert power (especially subconscious power) borrow from one another extensively. He discusses the military-industrial origins of Muzak, the use of "sonic branding" via jingles and earworms, and the use of sound as a weapon, in both historical and speculative near-futuristic contexts, from the abeng drum used by the Jamaican Maroons against British colonial forces to the modern development of Long Range Acoustic Devices, and the use of music and sound as torture, in Guantanamo and Iraq in particular. One powerful example describes the effects of the Israeli army's use of nighttime "sound bombs" in the Gaza Strip in 2005:

"A sonic boom is the high-volume, deep-frequency effect of low-flying jets traveling faster than the speed of sound. [The bombs'] victims likened its effect to the wall of air pressure generated by a massive explosion. They reported broken windows, ear pain, nosebleeds, anxiety attacks, sleeplessness, hypertension, and being left 'shaking inside'… dread of an unwanted, possible future is activated, perhaps all the more powerful for its spectral presence."

In interviews Goodman is often keen to separate the two, but there are connections between his academic research and his music: if nothing else, both explore the potential for the physical and psychological manipulation of human beings through sound. Goodman moved to London 15 years ago in pursuit of the urban dance music he loved - jungle, garage and, later, dubstep and grime. Yet the metropolitan context of these fast-evolving musical forms is essential to them, and the "creeping military urbanism" that Goodman describes in Sonic Warfare is an important ingredient of that.

Global urbanisation continues to change human, social behaviour and, indeed, military behaviour towards humans. Since the development of air warfare, the boundaries of historical, horizontal land-based conflict have been blurred: no longer are the front lines of conflict trenches in the countryside, clearly demarcating two warring armies. Urbanism demands new military methods and devices. The voguish non-lethal sonic weaponry researched by Goodman sounds unreal, but is innovating all the time to match the technology available.

The internet and international population migrations have also changed the hitherto relatively localised evolution of pop music; again, no longer are there rigid horizontal trenches between towns, communities or countries. And the urban environment is itself a sonic battlefield - in megacities such as London, ever-increasing noise levels from cars, planes and other people are the cause of heightened psychological stress, antisocial tensions and sometimes violence.

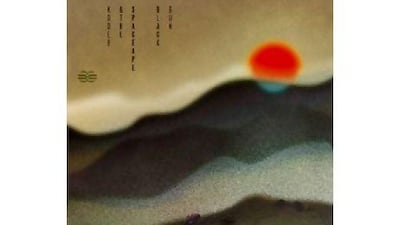

Goodman's record label, Hyperdub, began a decade ago, initially as a web magazine documenting urban, Jamaican-influenced London club music. Since releasing its first record, Kode9's own Sine of the Dub in 2004, the label has acquired a fearsome reputation for groundbreaking electronic music, tracking the paths through spacious sub-bass heavy dubstep, the deeply evocative urban melancholia of Burial's critically revered albums and EPs (his 2007 album Untrue topped some best-of-the-decade lists), through synthesiser-led electronics ranging from sleazy to futuristic, from psychedelic to emotional, and now, with Kode9's second full-length album with Spaceape, into terra incognita.

The pair's earlier work for Hyperdub drew deeply from the sense of nameless dread, of unplaceable but unmistakable fear evoked by Jamaican dub productions. Here you learnt to "dance to the gaps" as Goodman once put it, to psychically fill in the missing beats on the dance floor, or at the very least to embrace them, and the narcotic, paranoid military step of classics such as 9 Samurai made 2006's Memories of the Future an intense, unsettling debut.

Since then, the virus has mutated, as Goodman explained recently, heralding the new strain: "By 2007 I was getting left a little cold by the greyness of dubstep: stuff that is literally just drum and bass, with no tone colour. That minimalism felt fresh at the time, but that freshness doesn't last - it leads to stagnation, and gets predictable." The latest mutation of the Hyperdub virus has responded to the influence of house music on London's multicultural club scenes, in particular a percussive, often instrumental type of house called UK Funky; a strain confusingly lacking in funk, but certainly with a direct, up-front dance-floor focus. The stylistic achievement of Black Sun is how unmistakably it remains a Kode9 record, even while the genre framework, the tempo - ultimately, the rules - have changed.

Goodman's regular vocalist, Spaceape, appears again here, and is as ever the verbal articulation of the spirit of Goodman's music - providing phrase-sketches of dystopias, abstracted poetry, narratives dismembered, as he puts it, with "a surgical knife", about private citizens and faceless authority. The opening track, Black Smoke describes a physical vulnerability in the face of post-millennium tension that is a nice example of the pair's aesthetic. Except that "nice" isn't the right word here: "under a spell of a random feeling … weak … agitated; momentary breathing … heavily … the body is tiring".

The backdrop is as ever, perfectly apt to the lyrics: a combination of murmuring backing vocals from a woman called Cha Cha, humming dreamily somewhere in the distance, and percussion that scuttles along, darting from one speaker to the other. Most awkward and noticeable are the zaps of synthesiser best described as electronic squeaks: they bring to mind Goodman's academic fascination with sonic irritants, and the audio itch - not that this music is designed to get on your nerves, exactly, but definitely to provoke a response from them. At several points on the album, Goodman seems to be toying with the fact that sound has the potential to do things more complicated to our brains than simply bring immediate, unequivocal pleasure. An earworm melody can make us merrily whistle along, it seems to say, but look what this noise can do.

While the sound-work on the likes of Black Smoke is fascinating, the album's peaks come when the queasy, poisoned synths Goodman uses on Love Is the Drug, Green Sun and the brilliant title track are married with a clinical, mobilising dance-floor-orientated beat. At these moments, tensions between nausea and ebullient physicality are evoked and then transcended. The synths seem to suggest that we humans are a race infected, perhaps by technology, perhaps by something else: together with Spaceape's lyrics, we know we're not in a good place. Yet the house beats send a different message. The gut response to this trio of tracks is "something definitely isn't right here - so why do I find myself really wanting to dance?"

The pair have created a loose album-long narrative about a bleak, radioactive future: the synths represent the radioactive rays emanating from the titular black sun. By sheer coincidence - it was written before the earthquake, tsunami and subsequent Fukushima nuclear crisis - the story underpinning Black Sun has some grounding in Japan: a country that has always fondly regarded their work, and one suspects, vice versa.

"When you tap into it, you shouldn't be surprised when these things happen," Goodman said in an interview with the British magazine The Quietus a week after the earthquake. "When you get down into that unconscious level, things don't have a past or a present or a future. So you're obviously going to get these coincidences where, when you fictionalise something that seems dystopian, reality coincides at some point."

This collision of time, the blurring together of science-fiction dystopias with a scorched-earth present, and the exploration of uncomfortable connections between the pleasant bass vibrations of a bass speaker and the horrifying military use of sound to instil dread in civilians, is what makes Goodman's interdisciplinary work so interesting - and this album such a compelling listen. All told, a virus well worth catching.

Dan Hancox is a regular contributor to The Review.