It's dark. Pitch black, in fact. A cockerel crows, a donkey brays, and evocative sounds of morning life in Bamako, Mali, flood the senses. A moped buzzes past. The call to prayer begins. Flinging open the curtains on another day in Africa isn't on the agenda, though, because we are actually 4,500km away, in the function room of an insurance company's head office.

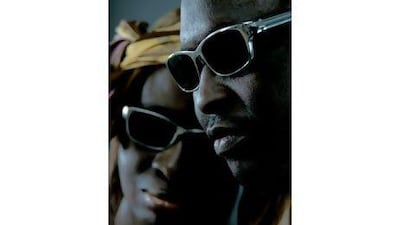

The sounds come from Amadou & Mariam, the world-famous "Blind Couple From Mali", who have just begun their latest project for Manchester International Festival: a series of gigs played entirely in the dark.

"If you cannot see, your sense of sound becomes richer," says Amadou Bagayoko, after the concert, entitled Eclipse, has finished. "I want the audience to hear the music just as Mariam and I hear it."

Is there a palpable difference to the experience of art when one's vision is taken away? That's the intriguing question which not only Amadou & Mariam play with here, but other musicians, playwrights and artists across the world have also begun to consider. Interestingly, the consensus is that, as soon as the lights go out, the focus is shifted from the artist to the audience.

When the indie band Friendly Fires played a similar gig in London a few years ago, it was partly a jokey attempt to overcome the drummer Jack Savidge's fear of the dark, but the group also wanted to encourage their fans to "feel" the music, rather than just hear it.

In fact, Marc-Antoine Moreau, Amadou & Mariam's manager and the co-creator of Eclipse, is sure that it's about more than just the music. "When you have your sight taken away at a concert, there is something psychologically different about your participation," he suggests.

"We're finding that anyone coming to the shows feeling at all unhappy on that particular day finds it quite a difficult, confusing experience. But if you're in a good frame of mind and open to what a concert in the dark might entail, then it really works. That's really interesting."

That openness is key to a similar concert series in London entitled Blackout. Here, audiences really are kept in the dark: not only are the lights off, but the bands' identities are never revealed, either. "The sensory distortion of total darkness forces a complete focus on the subtleties of sound," said the organisers Eat Your Own Ears, just before the first gig in May. "For the artists, absolute anonymity creates an opportunity to perform and experiment free from expectations and preconceptions."

Imagine the look on hundreds of hipsters' faces if the lights went up and they suddenly realised they'd been listening to someone really uncool.

I jest, but the interesting by-product of such events is that they are much more confrontational than one might expect. It soon becomes clear at Amadou & Mariam that the usual concert conventions will not apply - because you can't see the band (or indeed the person sitting next to you), there's no sense of a communal, joyful experience that one might usually expect from any successful touring group. It becomes, instead, a very personal, introspective 90 minutes - which is not always that easy to cope with.

"It wasn't like a normal concert," admits Bagayoko. "The audience were very calm and seemed to concentrate a lot more. They weren't even sure whether to applaud after we'd finished a song. So yes, it is a much more personal experience."

"And that has been interesting because usually I love giving off my energy to people in a normal concert," adds Mariam Doumbia. "It's like an exchange of feelings; even though I can't see them, they can see me. But in this case I can't do that so, to me, it feels more like a film or a piece of theatre. Eclipse is more cinematic in that way."

A film, of course, without any images. But Eclipse teems with soundscapes of Africa in between each song, storytelling from the poet Hamadoun Tandina and even evocative smells pumped into the space - although Moreau admits that the latter sensory experiment still needs a bit of work.

In a way, they were free to create their own narrative, which was also the concept behind The Question, a piece from the Extant theatre company, performed to great acclaim in London last year - once again, entirely in the dark. The piece asked its participants to navigate around Battersea Arts Centre, robotic lotus flower in hand. When the audience members approached something of interest, its petals unfurled as if bidding them to remain longer, and fragments of narrative were triggered.

The idea - to "transcend the normal divide between blind and sighted" - is something Amadou & Mariam can certainly empathise with.

"You know, we've thought about doing this for years," says Bagayoko. "People often ask us how we feel as blind people, and it feels like this is our answer, in a way. Being blind doesn't necessarily make you good at music, it just makes you concentrate more when you listen to it. Eclipse is all about making people feel and understand that, too."

It's probably overstating matters somewhat to suggest that turning the house lights down is becoming a trend - after all, the theatre company Sound&Fury was hitting the headlines way back in 2000 with its take on theatre in the dark, War Music. But we're certainly becoming increasing intrigued by it. Amadou & Mariam's concert was sold out. Blackout was also turning people away. And when the celebrated German artist Gregor Schneider brought his Kinderzimmer installation to Manchester recently, there were queues around the gallery to experience, essentially, a dark, empty box with the outline of a doorway in the distance. "The visitor will find nothing except his own inner experiences in that space," he said, rather moodily, at the time.

Which, despite the sheer joyfulness of Amadou & Mariam's music, is the point of Eclipse, too. "It's about using and feeding your imagination," says Bagayoko. "And, perhaps, a way of discovering sensations you never knew you had."

And you don't get that from a Take That concert.