When Lebanese businessman and music composer Kamal Kassar acquired the Abdel Aziz al Anani Arab Music collection, upon the recommendation of music historian and author Frederic Lagrange, the idea for a foundation committed to preserving traditional Arab music was born. In 2009, Kassar, together with Lagrange and a group of collaborators, founded Arab Music Archiving & Research, or Amar.

The aim was to put an emphasis on the nahda music tradition.

“What we’re doing at Amar is trying to give the aesthetics of the Nahda period a chance of existing alongside other types of music,” says Akram Rayess, one of the founding members of Amar.

“The aesthetics predominant before the 1930s were consistently marginalised, but also in certain instances associated with redundant or non-progressive values,” says Rayess, who is also an ethnomusicologist and steering committee member of the Modern Heritage Observatory, a network of organisations that works towards the preservation of modern cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa.

The pre-1930s aesthetics Rayess points to here are those of the Nahda era, also known as the Arab revival or Arab renaissance age, which stretched from the second half of the 19th to the early 20th century. That was a time when improvisation formed the essence of the maqam musical form. Arab musicians performed and improvised concurrently.

But such improvised musical expression, as Rayess goes on to explain, was brutally replaced, as well as deliberately overshadowed, with a new music aesthetic that became dominant in the 1930s. Increased westernisation, palpable in both education and lifestyle, was one precursor to this change. It was paralleled by the appearance of film musicals that endorsed large orchestras and drifted away from maqam music. Music magazines and media also reinforced this trend.

Over the years, however, and particularly since the 1980s, there have been persistent efforts to challenge the effacement of, as well as celebrate, the nahda music tradition.

Amar, therefore, sprang out of “an incremental interest in the Nahda period that has been growing since the 1980s through the efforts of researchers, most of whom were based outside the Arab World and who encouraged an appreciation for this kind of music.”

Among these researchers is prominent musicologist, composer and performer Ali Jihad Racy in Los Angeles, who did his PhD dissertation in the 1970s on the influence of the recording industry on nahda music, Rayess says.

Operating in Qornet el-Hamra village in Lebanon’s Metn District, Amar functions under the artistic direction of Egyptian performer, composer, researcher and musicologist Mustafa Said. To date, it has acquired around 11,000 78rpm records, and 6,000 hours of recordings on reel. It has one of the largest collections of Egyptian and Syro-Lebanese nahda music, as well as Lebanese studio recordings dating back to the 1950s.

One way the foundation shares these recordings with the public is through its CD packages, in addition to other digital formats.

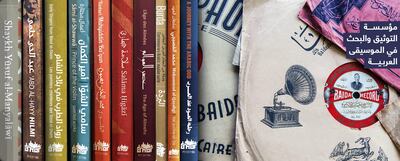

“We have a repertoire of at least 12 CD releases covering main themes or figures of the Nahda [era], from Yusuf al Manyalawi and Abd al-Hayy Hilmi to Sami al Shawwa and Tanburi Muhyiddin Ba’yun,” Rayess says.

The al Manyalawi anthology that Rayess mentions was released in 2011 in 10 CDs and two books. The records “represent all facets of Manyalawi: dawr, qasida, mawwal, muwashshah and layali type improvisations, among others,” as explained on the foundation’s website.

As part of its efforts to safeguard this musical heritage and disseminate knowledge about it, Amar also organises collaborative exhibitions with the aim of saving the “endangered oral musical heritage of the Arab world [threatened] because of technology or wars and conflicts or of changing social values,” Rayess says.

Amar’s first collaborative exhibition, [sound] Listening to the World, was held in 2018 in partnership with the Phonogramm-Archiv of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt University of Berlin.

This was followed by L’Orient Sonore, held in July 2020 at the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations, or Mucem, in Marseille. Both exhibitions were curated in association with Amar board member and vice president Fadi Yeni Turk.

“The mission of these exhibitions is to project well documented, well researched, non-commercial, non-cliché, and non-orientalist portraits of Arab music, pertaining mostly to the Nahda period, through shellac records and other documents, in addition to more recent and original field recordings of endangered oral Arab musical traditions” Rayess says.

Amar also produces its own podcast, Rawdat al-Balabel. To date, 200 episodes were released in collaboration with Sharjah Art Foundation, with the aim of “spread[ing] the rare musical heritage in our possession.”

“The podcast series was [planned] based on the repertoire of nahda recordings we have. So each episode is dedicated to a musical figure or a specific genre or musical theme, and the recordings used on these episodes are primarily extracted from original shellac records,” Rayess says.

“They are accompanied by discussions, explanations or analyses either done directly by Mustafa Said or through guest specialists,” he says.

The podcast, which ran a series of episodes on the late Egyptian musician and composer Zakariyya Ahmed, is user-friendly and widely accessible, with all of the episodes transcribed into Arabic as well as translated into English.

In terms of its future plans, Amar plans to tour with their Listening to the World exhibition, as well as more music acquisitions, currently under way.

“We’re also planning to do more field recordings of endangered oral traditions in further locations across different Arab countries,” Rayess says. Much of these future plans are contingent on funding, he points out, but countries of interest include Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Libya and Morocco among others.