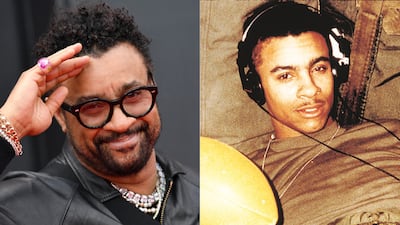

Shaggy's gruff baritone may have been refined in the studio, but the guttural appeal was first appreciated during the Gulf War.

During a five-month stint from December 1990, the Grammy Award winning dance-hall singer and former marine was deployed in Kuwait. According to the US Department of Defence news report, Shaggy, whose real name is Orville Burrell, was discharged in 1992 after attaining the highest rank of lance corporal.

Speaking to The National ahead of his Dubai Coca-Cola Arena show on Saturday, he remembers the period relatively fondly for the professional skills he gained. That includes developing his bombastic vocals while calling cadence during military training.

“That deep tone that people know me for comes directly from that – it's the voice of some of my biggest hits like Mr Boombastic and Oh Carolina, so when I eventually got out of the military and went back to music it was a matter of just transferring that to the studio,” he says. “Singing cadence was really helpful because you learn about voice projection, rhythm and really knowing how to sing from the gut.”

It also taught him how to move with intent as Shaggy’s career successfully navigated some of the seismic changes disrupting the music industry at the time. The biggest was the arrival of streaming technology, first heralded by the arrival of the controversial file sharing application Napster in 1999.

Shaggy is not surprised that he never had a bigger-selling physical album than his 2000 blockbuster Hot Shot, home to chart topping singles Angel and It Wasn’t Me. The album shifted more than nine million copies.

“Everything changed because after that album downloading really came in and streaming after that,” he says. “This is why I believe that Hot Shot was one of the last big albums of its era. I mean, in only a couple of years the label that released it shut down.”

Born in the Jamaican capital Kingston, Shaggy’s found immediate success in 1993 with his debut single Oh Carolina. A dance-hall remake of the 1960 ska hit by the Folkes Brothers, the landmark track was one of the earliest instances of Jamaican popular sounds crossing over to the US and European charts, thus laying the groundwork for the dance-hall wave to come.

Shaggy's deft ear for reinterpretation scored him more hits with In the Summertime, a 1995 remake of the 1970 song by British rock band Mungo Jerry, and Why You Treat Me So Bad, which had elements of Bob Marley's 1970 song Mr Brown.

That said, his biggest song, It Wasn’t Me, was an original co-written track inspired by a segment in Eddie Murphy’s stand-up comedy special Raw.

Despite its playful nature, Shaggy denies the song is an infidelity anthem. He points to the final verse in which the main character heeds the advice of his friend and decides to make amends for his actions:

“We should tell her that I'm sorry for the pain that I've caused,” goes one of the lines. “You may think that you're a player but you're completely lost.”

While the twist in the tale may be lost, Shaggy says It Wasn’t Me endures because it does what every good love song should.

“It has to be relatable in that it's either you who experienced what is going on, you know someone that is doing it or you wish it was you,” he says. “Everybody has experienced relationships in some way and as long as the music is relatable then it works. History proves that if it ain't broke, you don't fix it.”

As for the popularity of dance hall, Shaggy says the scene requires some fine tuning. Once a mainstay in the charts, the genre’s appeal has been gradually overtaken by new sounds from Africa such as modern Afrobeat and Amapiano. Shaggy’s diagnosis of dance-hall’s malaise is delivered with the directness of a drill sergeant.

“We could have been like any of these genres but we lack work ethic, the knowledge and the will to organise,” he says. “I am not mad because I feel that I have done my part and will go down as one of the movers and shakers of the scene.”

If the words seem like Shaggy’s parting letter to dance-hall, that is partly true. His last straight genre release was Wah Gwaan in 2019. It was sandwiched between 2018 collaborative pop album with Sting 44/876 and his 2022 Frank Sinatra covers album Com Fly Wid Me.

Produced by Sting, the latter collection is one of the rare occasions when you can hear Shaggy's natural range. It is, perhaps, the kind of voice his Gulf War comrades could have heard between drills.

“Sting is the brother I never knew I needed because he heard me and knew that I could sing like that,” he says. “I didn't think I could do it but he knew my ability and guided me. I learnt so many things and my ears are way sharper now as a result.”

While we can expect more interesting sounds from Shaggy in future, it will be behind the scenes as a producer. “I enjoy this because that's where I am getting the most satisfaction and until I get inspiration I'm not going to push the Shaggy issue when it comes to recording,” he says. “But I love performing live because I know I have a distinct sound that people love.”

Shaggy performs on Saturday at Coca-Cola Arena, Dubai. Doors open 8pm; tickets from Dh199; coca-cola-arena.com