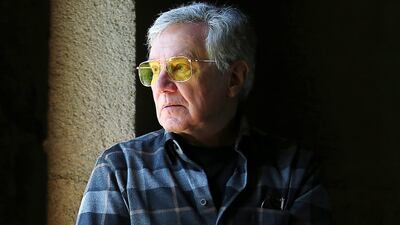

Since his groundbreaking work with leading rock 'n' roll bands of the 1960s, Bernie Krause has remained at the forefront of sound engineering. The soundscape artist, synthesiser pioneer and environmental activist's latest project is an immersive audiovisual experience that serves as a visceral wake-up call about the ongoing destruction of natural habitats.

A multisensory tour de force, The Great Animal Orchestra, playing at San Francisco's Exploratorium until October 15, draws on Krause's decades spent recording 5,000 hours of animal sounds. In that time, almost 70 per cent of the habitats he has recorded have gone silent or extinct.

“The Great Animal Orchestra reveals a profound loss of biodiversity due to climate change and human impact – I hope it will inspire individual agency or even collective action to protect our fragile ecosystems,” says the Exploratorium’s executive director Lindsay Bierman.

He thinks showing the project at a museum that puts equal emphasis on art and science is particularly poignant today. “As a self-described museum of art, science and human perception, I can't think of a better place to present this immersive experience to visitors of such diverse ages, backgrounds, perspectives and identities than here.”

For the show, Krause collaborated with Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, where the audiovisual experience launched in 2016. Various stops in Europe and Asia followed, with a show at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, coming after that. It's now making its west coast debut in San Francisco.

Pulled from Krause’s archive of recordings spanning decades, the experience occupies a 1,500-square-foot space with a shallow pool installed across the gallery floor. From deafening howls to mysterious pockets of silence, the sounds play to the universe’s daily equilibrium, mainly unbothered by human intervention.

The 98-minute-long score of animal sounds also features radiant light-filled spectrograms, created with the help of British artist Matt Clark of the collective United Visual Artists.

Strips of colour envelop the dimly lit gallery in neon shades and monochromatic abstractions that leave ample room for the rich soundscape to breathe. The sonic immersion traverses Krause’s half-century-long audio material – from Alaska to Africa – with sounds from at least 15,000 terrestrial or marine species.

Known for his collaborations with artists such as The Doors, Mick Jagger and Brian Eno throughout the 1960s, as well as spearheading the Moog synthesiser’s popularity in mainstream music, Krause first began immersing himself in his home town Bay Area’s natural orchestra for inspiration in the 1970s – exploring and recording its natural environments.

His initial encounters led to an album titled In a Wild Sanctuary in 1970 with his Moog collaborator Paul Beaver – named after Wild Sanctuary, an organisation he founded with his wife Katherine two years prior, dedicated to archiving natural soundscapes. After receiving his PhD in Creative Sound Arts in 1981, he gradually left music and began completely focusing on soundscapes.

“The expressions of the natural world speak to me personally – when I started recording the healthy habitats decades ago, I physically felt stronger and more present,” he tells The National.

Working on the soundtracks for films such as Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Apocalypse Now (1979) has also had an unexpected influence on Krause’s soundscapes. “In films, sound and music are the last component added to the media, but here we turned the concept on its head: sounds lead the vision.”

The main difference he finds between his work in Hollywood and the natural world is what he calls “the cultural bias". He adds: "Nature’s sounds are telling their own story without any bias.”

As time went on, Krause noticed the story was one of environmental decay. “Most of those habitats can no longer be heard in their original form; they are either unrecognisable or completely gone.”

Krause initially turned his 50-year journey of chronicling this drastic environmental deterioration into a 2012 book titled The Great Animal Orchestra. About his decision to present his research in art form, he says: “If I wrote a scientific paper, maybe six colleagues would read it, but when I use the scientific data and recordings in another medium, like art, the message eloquently speaks for itself.”

Krause, 85, considers the book “a story of how animals have taught us to dance and sing, with a rich narrative". Before the project took on its final phase as an immersive art installation, Krause also collaborated with the BBC on a ballet for Alonzo King Lines Ballet in San Francisco called Biophony – a term he coined to describe the collective symphonic soundscapes of the world's natural habitat.

“We are allowing the animals, who are the real artists, to express themselves, and what they are expressing is loud, clear and unassailable,” Krause says. “We cannot argue with our effect on that.”

The installation is framed by a dark, reflective pool of water, which runs alongside the walls, opening up the space considerably, and helping viewers to grasp the low-frequency components of certain phenomena, such as the sounds and natural vocalisations of oceans or thunder. While the streaming graphics are projected on to the walls and reflected by the mass of water, these inaudible elements are captured on the liquid surface as visible vibrations.

Beyond the beautiful green, red and blue washes of light colouring the placid water, the work is a wake-up call. The alarming rate of loss of the project’s subjects echoes through the high-pitched chirps of birds, the squeaking whirrs of insects and dominating howls of mammals.

The venue is also a fitting place for Krause, who began the Great Animal Orchestra journey charting the devastation of the region's rich natural habitats first-hand. In 2017, he and his wife lost most of their belongings and some archives due to a wildfire – something they have mourned alongside the loss of the natural surroundings.

Krause invites viewers to take their time and listen to what the universe that is free from human intervention is saying. “The sound of the natural world has been diminishing very quickly since the fall of the Berlin Wall,” he says.

“The narrative sound comes from all organisms, birds, mammals, insects, reptiles and amphibians.”

Krause says the ideal time to record soundscapes is at dawn – when birds and insects are most vocally active. However, he notes the death of three billion birds in North America since the 1970s and the disappearance of 70 per cent of the insects in Germany, as cited in a recent study in the journal Science as signs of an impending catastrophe.

“We have seen a tremendous drop [at this time of day] and already had two complete silent springs this year."

It is precisely that growing silence that helps the show's message come through louder than ever.

The Great Animal Orchestra is playing at San Francisco's Exploratorium until October 15. More information is at www.fondationcartier.com