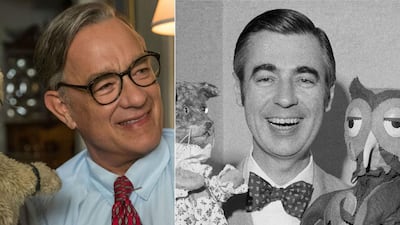

On a recent episode of Jimmy Kimmel Live, Tom Hanks discussed his new movie in which he portrays Fred Rogers, the much-loved host of the American children's show, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.

"You put on that red sweater and those blue shoes, you might as well be putting on Batman's cape and cowl," Hanks said, referring to the show's famous opening: Mister Rogers enters his house, swaps his jacket and shoes for a cardigan and trainers, and sings: "So let's make the most of this beautiful day / Since we're together we might as well say … Please won't you be my neighbour?"

Hanks's comparison seems faintly ludicrous, and not only because Rogers himself disapproved of television superheroes. Can you imagine a cardiganed crusader, whose powers include singing tender songs of self-empowerment, showing children how to wash up and puppeteering?

Nevertheless, the belief that Rogers is genuinely heroic has gained traction over the past two years. Suddenly, a man whose career began on black-and-white television in 1953 is all the rage in 2020. A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, which has earned Hanks his sixth Oscar nomination, succeeds Maxwell King's 2018 biography, The Good Neighbor, and Morgan Neville's documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor (also 2018), which has already become the highest-grossing non-fiction biopic in American history.

Memorable scenes include 10,000 people queuing for Rogers's first public appearance in 1968 (the organisers expected 500), and a nervous Mister Rogers single-handedly persuading grouchy Republican senator John Pastore to fund Public Broadcasting Service a year later.

Reinforcing this cultural renaissance are new collections of Rogers's lyrics and songs, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood: The Poetry of Mister Rogers (voted Goodreads' Best Picture Book of 2019) and, most importantly, the original show available to stream on Amazon Prime, The Best of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.

While this summary outlines the fuss, it doesn’t really address what the fuss is all about. The answer begins with Fred Rogers himself.

Born in 1928, he studied music, before becoming an ordained minister who researched childhood development "to understand the inner needs of children", as he told Pastore. These varied interests inform his somewhat unlikely television career. Mister Rogers was soundtracked by a live jazz trio, whose unassuming sophistication matched Rogers's sincere but cheerful tone. The primary themes of community, communication and caring are reflected by the show's repeated key words: neighbourhood, friend and special.

The experience of first watching Mister Rogers might feel jarring. In this, I include myself. Born in England, I didn't encounter the neighbourhood until adulthood, when my American wife showed this cherished show to our young daughter. My initial bafflement is partly because Mister Rogers is the polar opposite of almost every contemporary children's entertainer, whose primary aims are to whip children into a frenzy and crack knowing jokes aimed more at weary parents than children's fertile imaginations.

It is perhaps easier to say what Mister Rogers is not than what it is. There are no cartoons, jump cuts, flashy effects or high-volume jingles. No over-caffeinated, self-consciously cool presenter ingratiating himself with his young audience – things that Rogers summarised to Pastore as "bombardment".

Instead, Rogers talks to his young viewer in a gentle, unhurried and unaffected fashion about almost anything – from housework to balloon manufacture and stone polishing to shoes. "We don't have to bop somebody over the head to make drama on the screen," he told Pastore. "We deal with things like getting a haircut, or the feelings about brothers and sisters, and the kind of anger that arises in family situations."

While the aim is broadly educational, there are no didactic attempts to instruct or moralise. Rogers leads by example, roller skating clumsily, admitting his shortcomings, but vowing to practise and improve. In 1969, at the height of American racial segregation, he washed his feet in the same bowl as Officer Clemmons, the neighbourhood's African-American police officer. He discussed, with similar candour, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, the Columbine school shooting and 9/11.

The importance of fun and imagination inspired the Neighbourhood of Make-Believe, a magical, if distinctly lo-fi, toy kingdom populated by puppets such as the pompously loveable King Friday the 13th.

Whether Rogers is getting real or making believe, what he advocates is close, careful attention – to other people and an everyday world that adults might take for granted, but which for children can be filled with wonder or anxiety.

It is Rogers's ability to express joy and optimism, while acknowledging children's fears and confusions, that is at the heart of his enduring appeal. The neighbourhood was a secure environment, created by the show's stable, if evolving formula, and the host's essential trustworthiness.

Viewed today, Mister Rogers' tranquil pace and mood provides a contrast, not just to most children's entertainment, but a global culture fuelled by distraction, consumerism, irony and discord disguised as debate. "I think it's much more dramatic that two men could be working out their feelings of anger than showing something of gunfire," Rogers told the Senate in 1969, to prevent his show being cancelled after government funding cuts.

For him, television wasn't a way to reach vast audiences, to achieve personal stardom or sell merchandising to susceptible minds: you still can't buy anything directly from Mister Rogers. Instead, it was a portal that allowed communion with a single viewer. As he told the Senate: "I give an expression of care every day to each child." In short, television meant friendship.

Judging by my daughter’s reaction, this is just as true today as it was for her mother. She sings the songs by heart, jumps off the sofa when the trolley begins the trip to Make-Believe and chats happily with Mister Rogers himself. As does her mother, on occasion.

Children have a sixth sense about who is authentic, decent and, well, nice. The premise of Hanks's movie is to investigate whether Rogers was too good to be true. Without wishing to spoil the ending, the answer just for once is no. Which is why I'll leave the last word to Mister Rogers. "Please, think of the children first. If you ever have anything to do with their entertainment, their food, their toys, their custody, their day care, their health, their education – please listen to the children, learn about them, learn from them."

A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is in UAE cinemas from Thursday, January 30