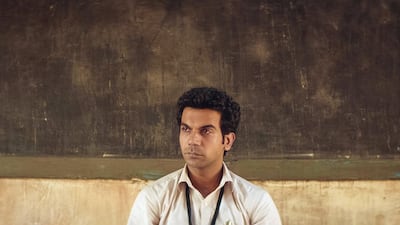

The film Newton – India's entry to the Best Foreign Film category at the Oscars – is a triumph on many levels.

It is political satire, a black comedy and a penetrating but gentle look at the complexities of Indian elections and the social realities in which voting can sometimes look absurd.

But it is also noteworthy for its hero. Newton Kumar is a Dalit, from the Indian caste formerly known as the untouchables, but the director, Amit Masurkar, refers to his caste so fleetingly that viewers could miss the only two references to it.

One is a picture of Dr B R Ambedkar, the most famous Dalit in Indian history who is revered by the community, hanging on a wall at Newton’s home.

The other is an irritable conversation that Newton has on a bus with his father, who admonishes him for thinking he can get an upper-caste bride.

Newton is an honest election officer sent by the government to conduct polling in a remote region and determined to do his duty. And it is this, rather than his caste, that dominates the film.

Bollywood has largely portrayed Dalits as oppressed, tormented by their caste, struggling for dignity, or exploited by the upper castes while living brutalised and wretched lives.

Two old films, Achhut Kanya (1936) and Sujata (1959), had Dalit protagonists but they were about caste discrimination and the gulf between them and the upper castes.

Dalits have never been shown as ordinary human beings simply getting on with life – until Newton.

“It appears that Bollywood is now ready to present a nuanced Dalit identity in its films, overcoming its earlier stereotypes,” Harish Wankhede, of New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, wrote on The Wire website.

Some Dalits have made strides over the past few decades, entering academia, the civil service, politics and to some extent business, and only partly because of affirmative action.

Yet they remain largely absent from Hindi films. The industry likes to think of itself as a place where caste and creed do not matter but there are no Dalit actors or actresses, let alone film stars.

Hindi films continue to feature leading characters from upper-caste backgrounds with upper-caste values.

Many Dalits see similarities between their own experiences and those of African Americans, first with slavery and then with segregation, and Dalit theorists liken caste discrimination to racism.

But while America has a whole galaxy of famous black stars, Dalits have yet to breach that barrier. For good reason.

Getting into films is extremely difficult without connections or a relative in the industry. Think of the Kapoors, the Chopras, the Bachchans, the Akhtars. A Dalit newcomer does not stand a chance.

With vast sums of money riding on a film, producers don't want to risk casting an unknown. In 2011, Chirag Paswan, the son of Dalit politician Ram Vilas Paswan, made his acting debut in the film Miley Naa Miley Hum, which flopped. With no more offers, Paswan went into politics.

“No one in the industry even thinks of anyone’s caste or religion,” says Nitin Tej Ahuja, a producer. “If Paswan’s film had done well, people would have been queuing to sign him up. Bollywood will chase wherever the money seems to be.”

Six years ago, director Prakash Jha ran into controversy when he cast Saif Ali Khan to play an educated, confident Dalit prepared to take on the system in Aarakshan.

Although some Dalit activists protested against the casting of Khan, who belongs to a royal family, playing a Dalit, the film at least showed that Bollywood was beginning to portray Dalits as more than just victims.

Regional film industries in Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh have begun to feature Dalit stories and lead characters.

The 2014 award-winning Marathi film Court, by Chaitanya Tamhane, was distinctive in not focusing directly on Dalit lives yet cleverly portraying the horrors of sewer cleaners (mostly Dalits) whose job is so terrible they can only stand it if they get drunk beforehand.

Sairat, by Marathi director Nagaraj Manjule, was a sensitive depiction of a couple trying to overcome the hurdle of caste.

But after 104 years, the Hindi film industry still has no Dalit star. One study in 2015 showed there were only six lead characters from a low caste in nearly 300 Bollywood movies in 2013 and 2014.

However, Dalit author and academic Kancha Iliaih, who lives in Hyderabad, says Bollywood simply does not care enough about Dalits. Hollywood could make a difference because, “the Indian elite is scared of the western media and of western opinion”.

But even there, hopes are slim. In 2005, Iliaih and other Dalits went to Los Angeles to try and persuade producers and directors to portray untouchability in India. Among those he met was African-American star Forrest Whitaker. But they had no luck.

“The people we met simply couldn’t understand how untouchability works on a daily basis – how, by touching a glass of water, a Dalit pollutes it for the upper castes,” Iliaih says.

“They couldn’t understand how untouchability operates in offices, markets, hotels, restaurants. ‘We can’t make a film about something we can’t understand,’ they told me.”

At the launch of a book by a Dalit author at the Jaipur Literary Festival, a sociologist declared: “The day Bollywood can give us a Dalit hero or superstar will be the day caste bigotry can really be said to have ended.”

That is unlikely to happen any time soon, says director Sudhir Mishra. But he agrees that when it does, it will be momentous.

“Once a Dalit is a film star, it means you have let him into your hearts and minds, that you admire him or her, that you fantasise about them, that you talk to them in your head. That would be thrilling and herald a real change.”