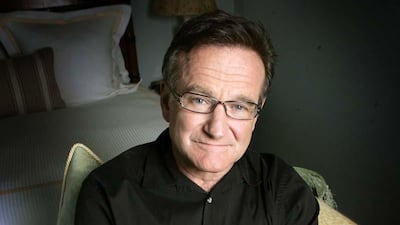

Sometimes a performer leaves a mark so indelible it's impossible to erase them from your mind. Like Robin Williams. Think of his zany extraterrestrial from breakthrough sitcom Mork & Mindy; the wisecrack-a-minute DJ in Good Morning, Vietnam, the role that won him the first of four Oscar nominations; or the cabaret-style Genie in Disney's cartoon Aladdin, surely one of the greatest voice-over performances of all time. All of them utterly unforgettable and utterly unique.

Today marks the sixth anniversary of the Hollywood star's suicide, a tragic loss keenly felt the world over. When word of his death spread, the hashtag #ocaptainmycaptain went viral on social media – a reference to his role in 1989's Dead Poets Society, as the inspirational English teacher John Keating, and the Walt Whitman poem O Captain! My Captain!, which sat at the core of Peter Weir's unforgettable melodrama.

The irony was not lost on fans; in the film, Williams's character was blamed for the suicide of a pupil. In reality, the actor and comedian took his own life due to a debilitating brain disease – Diffuse Lewy Body Dementia (DLB). A progressive illness, the disease causes severe cognitive decline, hallucinations and impairment of motor functions, so it was a brutal end for a man such as Williams, whose verbal dexterity and speed of thought were his stock-in-trade.

Williams had suffered from addiction to alcohol and drugs, and had spent time in rehab over the years, but DLB was a very different affliction. "It was not depression that killed Robin," noted the actor-comedian's widow, Susan Schneider, at the time. "Depression was one of, let's call it, 50 symptoms, and it was a small one." Even now, Williams's death is a sharp reminder of how unfathomably complex mental health issues are, and yet all too often they remain off the table, taboo in public circles.

"He is an electric, brilliant talent, yet his own personality is couched in anxiety, if not guilt," wrote David Thomson in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, an assessment – written a decade or so before his death – that ran unerringly close to the bone. In the latter part of his life, crippling divorce payments from his first two marriages and a run of movie flops had also preyed on his mind. Shortly before Williams's death, his new CBS sitcom The Crazy Ones was cancelled after one season.

There were times when his career was almost pointing, prophetically, to the struggles that would eventually claim his life. One of Williams's most famous roles – his Oscar-winning turn in 1997's Good Will Hunting – was as Dr Sean Maguire, a psychology tutor and therapist devoted to helping others with their mental health problems. His Oscar didn't change perceptions, though. As he told Marc Maron on the WTF podcast in April 2010, "One week later people are going, 'Hey, Mork!'"

Hollywood is, of course, a cruel beast at the best of times. In May 2019, the Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett comic novel Good Omens finally made it to the small screen with a lavish production by Amazon, starring David Tennant and Michael Sheen. For years, Terry Gilliam – who directed Williams in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and then to an Oscar nomination in The Fisher King – had wanted to turn it into a film.

Back in 2002, he had Williams lined up to play the angel Aziraphale, opposite Johnny Depp's devilish Crowley, two ethereal characters determined to save the world from the impending apocalypse. But all the studios balked at fronting up $15 million (Dh55m) to add to the $45m already raised elsewhere. This was pre-Pirates of the Caribbean and Depp was still considered an art house actor. And Depp's co-star? "Nobody was interested in Robin Williams," Gaiman told me last year.

It's a shocking statement. True, Williams's biggest hits – such as Mrs Doubtfire and Jumanji – were behind him. But he was also then in the midst of one of the most fertile parts of his career, when he turned to his darker side – playing a killer in Christopher Nolan's Insomnia and a loner who becomes obsessed with a family in One Hour Photo. It was a remarkable about-turn after years of slightly saccharine roles in films such as Patch Adams and What Dreams May Come.

I interviewed Williams twice over the years. The first time was in 1999 after the release of Jakob the Liar, set during the Second World War. The day before, at the press conference, he'd told a joke about Hitler, impersonated Peter Lorre and mocked the French, all in the space of several hilarious seconds. The comedy gods had shone, he later told me. "The rules were off. It was no longer a press conference. It was stage time." It was classic Williams – the unstoppable entertainer.

Williams's parallel career as a stand-up comedian was where he could get really dark, he told me. But even then he was seeking to bring that darkness into movies. "The only way to spin my career differently is to play a serial killer," he said, citing his role in Christopher Hampton's 1996 film The Secret Agent, an adaptation of the Joseph Conrad novel. "He was an alchemist who made bombs. An effort to make a character non-human. I've looked for them, but most people send me positive characters. I'm not afraid to play them because it helps."

The second time we met was a more low-key encounter – Jack Nicholson and Al Pacino impressions notwithstanding – offering proof that the Chicago-born Williams was as thoughtful in person as he was manic. He was 52, then, happy with his recent turn towards "darker, tougher" roles in mid-budget movies. "There are things at stake," he explained, "but it's not the same pressure [as being a studio lead]."

The film in question was sci-fi The Final Cut, typical of the indie movies he'd moved towards and further proof that the Juilliard School-trained Williams could still cut it dramatically. Playing Alan Hakman, a man responsible for editing human memories into video clips for funerals, it gave Williams pause for thought. "You're very much aware of what will you be remembered for. My family. That's one thing. Your work."

It's a legacy that now speaks for itself. As his daughter, Zelda, said soon after his death, the "world is forever a little darker, less colourful and less full of laughter in his absence". Even 2019's popular live-action Aladdin remake, with Will Smith as the Genie, felt like a poor imitation. But then who could ever touch Robin Williams? He was a comedian who wrestled with his dark side but never failed to light up any room he walked into.