It was June 21, 2001, when Soad Hosny fell six floors from the balcony of a friend’s home at the Stuart Tower in London’s Maida Vale neighbourhood. On this day 23 years ago the Arab world lost one of its greatest stars.

An actress and singer, Hosny was a symbol of a transformative time not only in Egypt but across the region. Early in her career she was dubbed the “Cinderella of Arab cinema”, a title that, in retrospect, encompasses more than just her journey to stardom, but her legacy in Arab culture.

Beautiful, talented, mysterious and charismatic, Hosny effortlessly instilled these traits through nuanced performances on the screen. There’s also an element of tragedy attached to her memory, both through the circumstances surrounding the end of her career and ultimately her death, and also in her personal life.

Born in Cairo, Egypt on January 26, 1943, she was one of 14 siblings in a modest, artistic family. Her father, Mohammad Hosny, was a renowned calligrapher and her half-sister is the famed actress and singer Nagat Al-Saghira.

At the age of three, Hosny was singing on children's radio programme Baba Sharo. In 1959, at the age of 16, she starred in her first film, Hassan We Naaema, an Arabic reimagining of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet set in rural Egypt.

From 1959 until her death in 2001, Hosny performed in more than 80 films, ranging from light comedies, musicals, romances and dramas to political thrillers.

“Soad Hosny is one of the most unforgettable artists in the history of the Arab world,” Egyptian film director Amir Ramses tells The National.

“She is one of the best raw talents we had in our history and that's what was special about her. That's why she's unforgettable. That's why she's in a very special place for everyone.”

Ramses, known for the films Curfew, Cairo Time and The Affair is also the director of the Cairo Film Festival. He believes Hosny possessed intrinsic qualities which drew audiences to her.

“Her performances were not just believable but also cheerful,” he says. “Not cheerful in the sense of comedy or a light film, but audiences knew they were going to see a cheerful performance.”

Many of Hosny’s roles challenged social convention and no matter the genre, her characters personified the modern pan-Arab woman in her complexities and contradictions.

“I love Soad Hosny and I am totally fascinated by her, she's an incredible and very talented actress,” says Lebanese filmmaker and video artist Rania Stephan. “She's a constant source of fascination. It never finishes because she is complex.”

Stephan is known for The Three Disappearances of Soad Hosni, a feature film co-commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation in which she attempts to tell the story of Hosny through a filmic montage. It is a moving tribute and exploration of Hosny through all her films that are woven together to tell a narrative of her life on the screen as well as to present a timeless portrait of the star.

“When she died, I was so shocked, like everybody in the Arab world, because I couldn't imagine that she could die … as an icon,” Stephan adds.

“I wanted to pay homage to her work. I felt like she gave me something and I had to pay her back. She gave me this curiosity about my own culture. She brought me back as a critical eye to inspect my culture differently and to see popular Arabic culture in a different way.”

In 2001, Stephan obtained 78 of Hosny’s 83 films on VHS tapes. She analysed them, creating a picture of Honsy’s legacy in conjunction with her personal life and the political social changes of Egypt at the time.

“The way Soad's filmic persona was constructed was an interesting combination and I didn't find the equivalent in Hollywood – it was very specific,” Stephan says.

“She has a variety of aspects that makes her persona complex, but the combination is strange. She's not only Marilyn Monroe; she's not only Shirley MacLaine; she's not only Judy Garland; she's a combination of all elements.”

The aftermath of the 1967 Arab-Israeli War transformed the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. That and influences from Hollywood moulded the Arab film industry and Hosny was at the heart of it.

“She was always lucky to be working with people who had a certain message to convey,” Ramses adds. “She also cared about finding films and projects that would be important for her, that touched her, and society.”

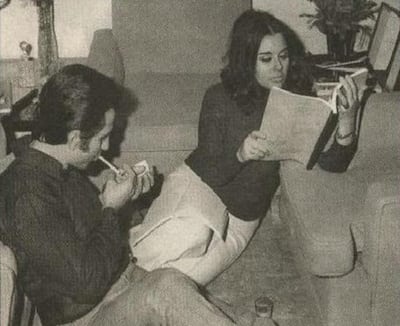

Despite a successful career, Hosny’s personal life was fraught with challenges. She was married four, possibly five, times throughout her life.

Her alleged first marriage to Egyptian film star Abdel Halim Hafez in 1960 was never officially confirmed. In 1968, Hosny married cinematographer Salah Kurayyem, a union which lasted for a year. Then in 1970, she wed Egyptian film director Ali Badrakhan. Their marriage lasted nearly 11 years and together they created some classic films including the celebrated film Shafika wa Metwali (Shafika and Metwali) in 1981.

Hosny then married actor and film director Zaki Fatin Abdel Wahab, son of the acclaimed actors Fateen Abdel Wahab and Leila Mourad in 1981. It was a marriage that allegedly only lasted a few months. Her final marriage was to the writer Maher Awad in 1987, which lasted until her death.

In 1979, while playing the role of a circus acrobat in the film Al-Motawahesha (The Fierce), Hosny slipped and injured her back. The accident was the root cause of neurological dysfunctions that would plague her for the rest of her life.

Following years of failed treatments in Egypt, she withdrew from public life and left the limelight for Paris in 1992. Despite back surgery, Hosny’s health continued to decline.

In 1997, Hosny sought more medical help in London but never left. Four years later at the age of 58, she was dead. Her body was flown to Cairo and her funeral was attended by more than 10,000 people.

Hosny’s death has been surrounded by speculation ever since. There have been unsubstantiated claims about her mental condition at the time of her death as well as potential plans to return to acting.

In 2016, Hosny’s sister, Janjah Abdul Mone’m, released a book entitled Souad: The Hidden Secrets of the Crime. Janjah claimed that Hosny was involved with the Egyptian secret service during the 1960s and was murdered in 2001 as she was planning to write her memoirs. Janjah’s book also provided an alleged marriage document, apparently proving that Hosny and Hafez were married in 1960 for six years.

The book was viewed by many in the public as propaganda to clear the family from rumours of their own strained relationship with Hosny while she was alive.

Given her health issues, the apparent drastic change in her physical appearance, her alleged financial situation and no longer being in demand by the film industry, many believe Hosny took her own life.

“Why were people invested in the fantasy, in the lore of who she was, of her life away from the camera? It's because she’s really loved,” Ramses says.

“Her charisma created a certain alliance between her and her audience. You feel like this actor belongs to you. It's more than a great actor. It's someone close to you.”

Despite the tragic circumstances surrounding her death, Hosny remains one of Egypt’s most successful leading ladies and one of the Arab world’s greatest stars. In 2022, on what would have been her 79th birthday, Google paid tribute to Hosny with a Google Doodle.

Like the fairy tale which inspired her nickname the Cinderella of Arab cinema, it’s Hosny’s real-life story as a humble, reserved young girl who found stardom through the power of her raw talent, charm and free spirit that continues to captivate millions and feed her enduring legacy.