Syrian writer Khalil Alrez looks for beauty even within war.

“There are plenty of novels published in recent years about war. Novels filled with blood, filled with the remains of the dead, filled with scenes such as those populating our TV screens,” he says in a video posted by the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (Ipaf) earlier this year.

“I offer my readers something beautiful, something different about an ugly and well-known subject.”

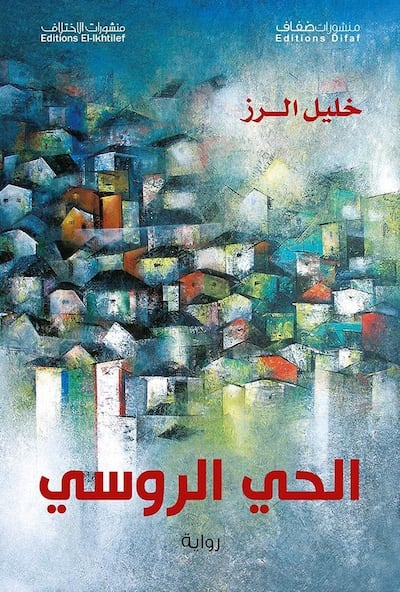

It is that pursuit of beauty within ugliness that propels the events in Alrez's latest novel, The Russian Quarter, which was shortlisted for the prize in February.

"You can write a beautiful and enjoyable novel, regardless of the topic you are dealing with, if your priority is to create art," Alrez tells The National. "Wars are truly catastrophic events, but when they are on your writing desk they become a landscape from which to make art.

"Napoleon's invasion of Russia was an ugly subject for Tolstoy's beautiful novel War and Peace. The destruction of the town of Guernica was an ugly subject for Picasso's beautiful painting."

Like most of the author's previous works, The Russian Quarter does not concern itself with traditional storytelling. Neither does it follow the tracks of a chronological narrative. Instead, the novel is written as a collection of scenes.

Its premise is this: war encroaches on the Russian Quarter, a fictional neighbourhood on the outskirts of Damascus. Its populace has, for years, resisted slipping into the bloody conflict that has upended the rest of the country and displaced its citizens. But now, it seems there is no staving off the war any longer. However, rather than picking up arms, the denizens of the Russian Quarter resort to telling stories to see that they survive through the conflict.

“One of the elements that distinguishes this novel from my previous works is the presence of animals as main characters,” Alrez, who has been living in Belgium for the past three years, says. “There are dogs, a cat, a giraffe and a sparrow made of wool, as well as a number of secondary animal characters.”

However, the animals in The Russian Quarter do not talk as they do in the Indian fables of Kalila and Dimna or in George Orwell's Animal Farm. "The animals are silent but they play a pivotal role in moving the story forward," Alrez says.

That is not to say that humans do not have a central part in the story as well. The novel is narrated by a translator living in the neighbourhood zoo with Nuna, a knitter. There is also Victor Ivanitch, a former journalist who now works as the zoo manager; a French teacher, Ali Suleiman; Rashida, an oud player in a cabaret; and Arkady Kuzmitch, a little-known Russian writer.

It may be a place of fiction, but the eponymous neighbourhood of Alrez's novel can be thought of as a microcosm of Syria, containing elements from three of its major cities: Raqqa, Aleppo and Damascus.

"The Russian Quarter has streets and places that are actually found in these cities," Alrez says.

The neighbourhood was also where the events of his previous three novels took place, including Where is Safed, Youssef? and In Equal Measure.

"To me, Syria represents my childhood, my mother, my father, my first friends and the unrequited loves I had as a teenager," Alrez says. "Syria has the first books I read, the first passages I wrote, and the places that I continue to explore and reimagine in my novels."

On why he chose to name his fictional neighbourhood the Russian Quarter, Alrez says that, after Syria, the country that had the biggest effect on his cognitive makeup and his writing was Russia.

“I travelled to Russia long before the war, in 1984,” he says. “I lived in Saint Petersburg and Moscow for close to 10 years. I studied the language and worked as a translator in a Moscow newspaper and then as a host for a cultural radio programme. The country made a lasting impression on me.”

Alrez returned to Syria in 1993, where he remained for a decade, publishing novels such as A White Cloud in the Window of the Grandmother, as well as translating works from Russian including Evgeny Schwartz's Tale About the Lost Time and the short stories of Anton Chekhov.

“I left for Europe in 2015 because of the war,” Alrez says. “I lived in Turkey and in Greece for more than a year before settling in Belgium in 2017.”

Alrez is now working on a novel that takes place “far away from the throes of war".

"I don’t know yet when I will finish it," he says. "I’m a slow writer. I don’t think it will see the light of day until more than a year from now”.