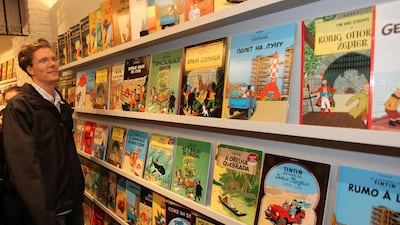

There are 24 books and five feature films dedicated to his adventures – most recently Steven Spielberg's 2011 version featuring Jamie Bell as the intrepid Belgian reporter – so Tintin is surely one of the Francophone world's best-known gifts to 20th century literature.

What you may remember as a fun comic book from your childhood is more layered than you would think, and a number of "Tintinologists" have dedicated their entire lives to studying the creation of Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, better known by his pen name of Herge. Perhaps the most recognised of these is Philippe Godin, who has published numerous books on the topic since 1986's Tintin Reporters: From Le Petit Vingtieme to Tintin Magazine.

Closer to home, the UAE has its very own Tintinologist in the shape of French diplomat and historian Louis Blin, whose book Le Monde Arabe dans les Albums de Tintin looks at what we can learn about the Arab world from Herge's books.

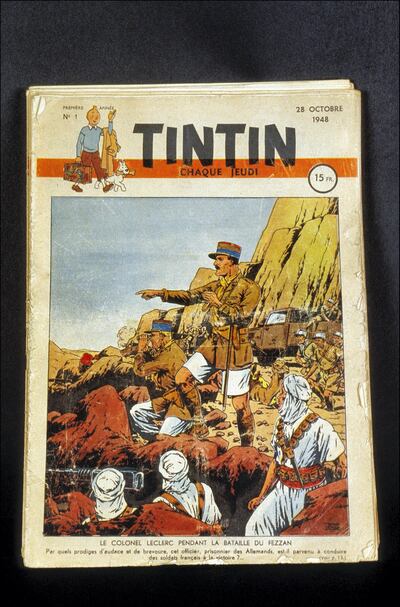

It's perhaps not surprising, given that Tintin cartoons were first published in the fascist-leaning Belgian newspaper Le Petit Vingtieme, that some of Herge's mid-20th century portrayals of the region were not entirely positive. The political morals of his stories were often required to fall in line with the publication's world view.

In fact, Blin claims that Herge had always wanted to set Tintin's earliest adventures in the Arab world, but due to pressure from his publisher his first story, which would eventually be published as the 1930 book Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, was a piece of anti-Marxist propaganda based in Russia.

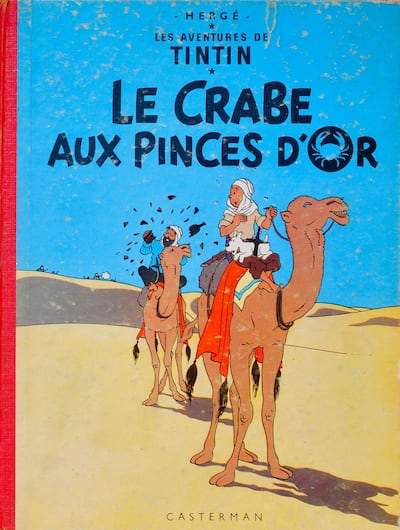

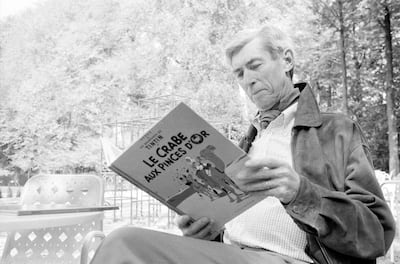

It was not until 1934's Cigars of the Pharaoh (which began serialisation in 1932) that Herge would finally get to send his hero to the Middle East, where he would return in three further books – The Crab with the Golden Claws (English book publication 1943), Land of the Black Gold (1950), and The Red Sea Sharks (1958).

Blin insists that this is no accident. “In our culture, in the French speaking world, you cannot avoid the fact that we are partly Arabs,” he says. “Herge may never have confessed it, but when he first began to experiment as a writer, began to invent Tintin, who is basically Herge himself, he began in the Arab world. That's not by chance. The Arab world is the mother of all of us, and Tintin begins his journey crossing the Red Sea, because Herge wanted him to be the new Moses. The first books to be published were in Russia, Africa and the US, but the first that he wrote was in Egypt, and that's not an accident.”

By the time of 1950's Land of the Black Gold, which began serialisation in 1948, Herge was already beginning to be something of a political outlier when it came to interpretations of regional events. "It happens in Saudi Arabia, and it's focused on the Jewish/Palestinian question," says Blin. "He was paying attention to this question long before anyone else was thinking about it, and he even linked it to oil, which wasn't even a big thing at that time in this region. All the oil was [perceived to be] in Central Asia and Iran."

Despite pressure from his publishers at various points in his career, Herge was himself largely apolitical, even an anarchist according to Blin, and this was evident in Land of the Black Gold. "He didn't take any sides in the book. There were Jews in it, and there were Arabs in it, but there were no good guys or bad guys. That wasn't Herge's way."

Unfortunately for Herge, it was the way of publishers in the mid-20th century. When the book was sent for English publication, the British publisher insisted that Jews had to be “good guys,” and that Palestine should be substituted with a fictional country. Rather than compromise his political neutrality, Herge opted to undertake a complete rewrite and remove all the Jewish characters from the English translation. Subsequent French editions have also been based on the English version, and only a few copies of the original, French language, first edition remain. This is surely one of the least publicised cases of historical revisionism in the literary world.

Blin explains: “He was a difficult man to understand. He didn't get involved in politics, he thought it didn't matter, so he wasn't interested in taking any sides. He was essentially an anarchist, almost a nihilist. What affected him most in his life was the German invasion of Belgium in World War I, and then again in World War II. After the first invasion he became a pacifist, and after the second he became nothing. He was simply disgusted by humanity. He came in for a lot of criticism because he didn't even take sides in World War II. He just found all of it disgusting, and that wasn't acceptable. If you weren't with us you were against us, was the view of the day.

“Herge had a very complicated childhood," Blin adds. "He thought his grandfather was the king of Belgium, and he may have been right, but it was never made public.

"He sent Tintin first to the Orient to find himself, and then in a later series of books Arabs come to Belgium. He discovers that even if somebody seeks himself in the 'Orient', it's useless because you have to discover yourself in your own place. Voltaire had a similar concept. You have to seek out knowledge and discover the 'other' of course, but ultimately you have to go back to yourself.”

Herge's innate sense of connection with the Middle East was perhaps unusual for the time, as evidenced by attitudes to one of the book's main characters: “It was a very racist time, but one of Tintin's closest friends in the books is a Sheikh called Abdullah,” says Blin. “It seemed incredible at the time that this 'servant of a foreign god' could be a friend of Tintin, or any European.”

Herge's portrayals of the region were far from universally positive, however. Blin concedes that there are parallels between Herge's portrayal of the region and current Hollywood stereotypes.

Tintin would make his final visit to the region in The Red Sea Sharks, which began serialisation in 1956, and was published in book form in English in 1958. It was around the time that many Arab states were gaining independence from the various pre-war colonial empires, and Blin says that, as the Arab world broke free from its European masters, so Herge realised that Tintin would need to return to Europe to truly find himself. Despite this fact though, Tintin's link with the region is, for Blin, unbreakable, just like his own link with the intrepid cartoon reporter.

“We grew up with Tintin. He was someone who everyone of my generation saw as our brother. He's a crucial part of our identity in France and Belgium,” he says. “Even those who weren't big fans use quotes from him without even realising it, his words have entered the French lexicon. There are characters in the books that we use as stereotypes every day in France. Tintin is in our blood, and the Arab world is in Tintin's, and Herge's, and all Europeans' blood. It's inseparable.”

Herge's Tintin books are widely available in bookstores. Louis Blin's Le Monde Arabe dans les Albums de Tintin is published by L'Harmattan