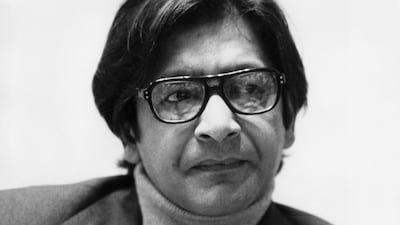

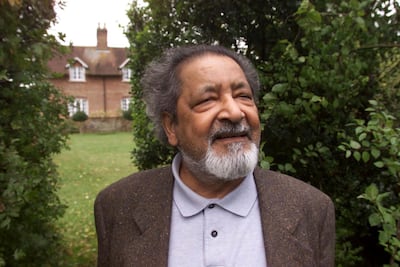

Few writers divide opinion quite like VS Naipaul, who died on Saturday, aged 85. To some, Naipaul was a stylist of rare brilliance, who wrote about the sufferings of mankind with an invigorating, occasionally brutal, honesty. To others, he was a racist, misogynistic bully, scornful of non-Western societies and ashamed of his own heritage.

The truth, as ever, is most likely found somewhere in the middle.

At his best, Naipaul could be incisive, vulnerable and exceptionally funny. He won the Booker prize in 1971 for In a Free State, his unflinching novel about colonialism in Africa, was knighted in 1990, and awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. Not even his most ardent detractors – and there are plenty of those – would seriously question Naipaul's place in the literary canon. Friend and fellow author Paul Theroux said: "He will go down as one of the greatest writers of our time."

And yet, for all this success, Naipaul could be cruel and spiteful. He relished arguments, fell out with friends, and seemed to delight in upsetting people. He described African societies as “primitive”, dismissed India as a “slave society”, and once said: “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two, I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think it is unequal to me.”

This contradiction between the man and his work was best summed up by Salman Rushdie, who paid tribute to Naipaul on Saturday evening. “We disagreed all our lives, about politics, about literature,” Rushdie wrote. “And I feel as sad as if I just lost a beloved older brother.”

Born in Trinidad: 'I thought it was a great mistake'

Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul was born on August 17, 1932, in Trinidad. His grandparents had emigrated, in the 19th century, from India to the Caribbean, where they worked on a plantation as labourers. Naipaul, whose father was a journalist, was desperate to leave Trinidad and would later distance himself from his birthplace. “I was born there, yes,” he said in 1983. “I thought it was a great mistake.”

In 1950, he moved to England, where he studied English Literature at Oxford University, before moving to London with his wife, Patricia Hale, and taking up a job with the BBC World Service. He began writing short stories and was encouraged by his publisher to produce a novel. In 1957, The Mystic Masseur, about a frustrated Indian writer, was published and promptly won the John Llewellyn Rhys Prize. Two more reasonably successful novels followed, including Miguel Street (1959), which won the Somerset Maugham Award.

Naipaul's major literary breakthrough arrived, however, at the age of 29 with the publication in 1961 of A House for Mr Biswas, which tells the story of an Indo-Trinidadian man who marries into a wealthy family, foregoing his independence. It received worldwide acclaim and was featured in the Modern Library's list of "100 best English-language novels of the 20th century". In 1983, in a piece for the New York Review of Books, Naipaul wrote: "I have no higher literary ambition than to write a piece of comedy that might complement or match this early book."

The trouble with his non-fiction work

After the success of A House for Mr Biswas, Naipaul, who published more than 30 books in a career spanning nearly half a century, devoted more time to travel and non-fiction writing, though he continued to publish novels until 2004. It was these works of travel writing that sparked most controversy and contributed to Naipaul's reputation as a bigot and Uncle Tom. In 1962, Naipaul wrote The Middle Passage, in which he criticised West Indians for capitalising on the tourism industry, claiming that they were "selling themselves into a new slavery". The Caribbean-born poet Derek Walcott accused Naipaul of having a "repulsion towards Negroes".

No subject seemed to be off limits for Naipaul, who criticised Islam (Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey), Africa (The Masque of Africa) and, in one of his most controversial books, An Area of Darkness, wrote that Indian people "defecate everywhere. They defecate, mostly, beside the railway tracks. But they also defecate on the beaches; they defecate on the hills; they defecate on the riverbanks; they defecate on the streets; they never look for cover." Naipaul's defenders argued that he was simply presenting an honest depiction of life in these countries, rather than a romanticised, patronising Western view. This, wrote the Turkish author Orhan Pamuk, had the effect of making "[the people] less victims and more human".

Naipaul’s personal life, too, was marred by controversy. He physically abused his mistress, Margaret Gooding, and admitted that the psychological abuse of his wife, Patricia, may have contributed to the breast cancer from which she died. “It could be said that I killed her,” Naipaul told his biographer.

Naipaul had a sharp tongue and indulged in endless literary feuds, perhaps most famously with Paul Theroux, who once described him Naipaul as an “interesting monster”. Their 30-year friendship faltered when Theroux discovered that Naipaul had tried to sell a signed copy of one of his novels online. The pair reconciled in 2011, however.

Many writers have criticised Naipaul, including Chinua Achebe, who described him as “a restorer of the comforting myths of the white race”. But none of this seemed to bother Naipaul. “When I read those things, I am immensely amused,” he said in an interview in 2009. “They don’t wound me at all.”

His softer side

For every barbed attack about Naipaul's views, though, there is a story about his personal kindness and vulnerability. Following Naipaul's death, British author Hari Kunzru recalled a time when he interviewed Naipaul. When Kunzru presented Naipaul with a first edition copy of A House for Mr Biswas, Naipaul immediately broke down in tears. Having recovered, he said: "I haven't seen one of those for so long."

For all the angry outbursts, then, perhaps Naipaul only really cared about his writing. And it is, surely, this writing – not always palatable but never less than candid – that he will be remembered for. By comparison, the unsavoury politics and the irascible temperament seem like inconsequential footnotes.

______________________

Read more:

No such thing as culture in Dubai? Pick up Proust

Author John Irving wins literary peace award

Refreshing reads for summer 2018

______________________