Dig into the foundations of any language and you'll find quite a few words rooted in body parts.

In English, for instance, the word "language" itself is a descendent of the Latin word "lingua", which means tongue, and the word "sarcasm" can be traced back to the Greek word "sarkazein", meaning “to bite the lip in rage".

Every language has a mass of words which are associated with the human body. In Arabic there is a treasure trove of words with origins to body parts, and two educators have released an illustrated book to show both native speakers and those learning the language just how much of the Arabic vocabulary has been inspired by biology.

"The body plays a huge role in language but it's mostly unconscious," Lisa White, a former Arabic instructor at the American University in Cairo (AUC) and Cornell University who has been teaching the language for 30 years, says. Its importance is usually overlooked in every language, she adds.

"We aren’t so aware of it but researchers working on embodiment theory say it’s kind of your body doing the thinking, in a way. Your mind is your body and it is governing the way you perceive the world and the way you talk about the world.”

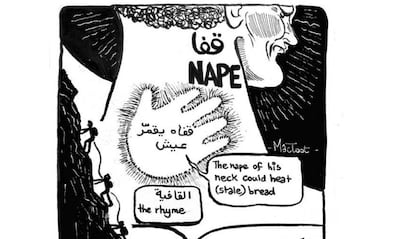

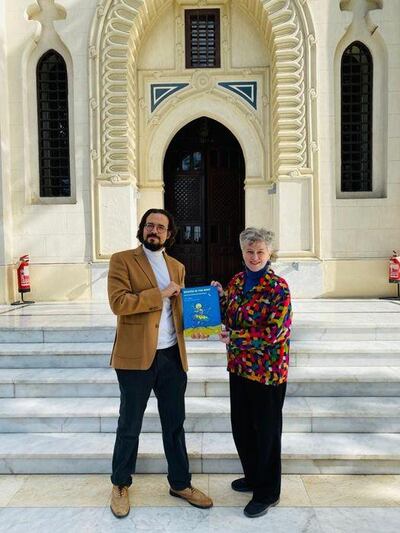

Rooted in the Body: Arabic Metaphor and Morphology features a collection of essays by White that investigate how a litany of words can be sourced back to 125 body parts. Each essay is complemented by a rich black and white comic illustrated by Mahmoud Shaltout, an associate professor at AUC's Academy of Liberal Arts and Institute of Global Health and Human Ecology.

White says though she began studying the Arabic language in 1975, it wasn’t until “much, much later” that the prominence of body parts in the roots of Arabic words became clear to her. Arabic, like most other languages, is hardwired to the body. And this connection is not just overlooked by students of the language but native speakers as well.

White first noticed this relationship while drafting worksheets for her students to match new vocabulary to the root word, an exercise that helps them link words better. The word "mutaqadim", meaning advanced or forward, lit a lightbulb in her head.

“Beside it, in parenthesis, I wrote ‘qadam’ or ‘foot’ and it just hit me,” she says. “That whole family of ‘qidam’ and ‘qadama’ was about forward motion. So where do you go on your feet? Forward, right? So the Arabs realised that the foot was a perfect metaphor to build on words with forward motion.”

Over the years, White discovered more words that developed from the names of body parts – from the jaw and the wrist, to the nape of the neck and the heart – and, in 2017, at the encouragement of her friends, she decided to compile them in a book.

"Each page in Rooted in the Body is dedicated to a body part," White says. "For instance, one page features the word 'ar-raqaba', which means neck. 'Ar-raqaba' is at the root of the word 'raqib', meaning to watch. The neck is the limb which helps us keep track of things so it makes sense that it's inspired the word."

The neck, White says, is also the root of words such as "raqeeb" in both its military context, referring to a low-ranking officer, and its definitions of close observer or keeper. The word is also at the root of "marqaba", meaning lookout or watchtower.

Facing White's essay on "ar-raqaba" is an illustration showing a long-necked bald man peering at the viewer from the corner of his eye. The word "taraqab" or "to be on the lookout" is written on his temple. He has been gagged with a folded fabric on which the word "alraqaaba" or censorship is written. Behind the man is a stern-faced, mustachioed officer as well as a watchtower.

White says she knew the book would be richer with illustrations and would convey the metaphorical aspect of the Arabic language in a more captivating manner.

"I couldn't draw a picture to save my life, though," she says. For her classes, the instructor would supplant her worksheets with images found on the internet. For Rooted in the Body, however, she wanted to make the images more interesting, so she began looking for an illustrator to collaborate with. Mutual friends at AUC introduced White to Shaltout, whose artist moniker is MacToot.

Though Shaltout's course offerings at AUC, which include Scientific Thinking and Current Health Issues, are a far cry from art, the public health PhD says he has always been an illustrator at heart.

“I’ve been drawing comics since I was 7 years old,” Shaltout, who is an alumni of the American University of Sharjah (AUS), says. “I was a cartoonist for my high school newspaper, AUS’s Leopard newsletter and when I went to the UK for my master’s degree, I was a cartoonist for the online paper at the university there.”

The illustrations in Rooted in the Body, Shaltout says, are meant to not only make the book more visually appealing and enjoyable to thumb through but also to serve as a way to help readers – particularly those interested in learning Arabic – retain the information.

"We're in a visual age, so having illustration really helps those learning the language," he says. The artist has peppered pop culture references from Alice in Wonderland to Umm Kulthum within the book's drawings to help make them memorable.

“I always illustrate my notes and carry that practice while teaching as well. So whenever I have a difficult concept to explain, such as the Big Bang or evolution, I’d try to draw them out.

“Comics,” he says, “are a great pedagogical tool.”

Rooted in the Body is already available for purchase via the AUC Press online store. The book is scheduled to be released on Amazon this month.

For more information about the project, visit aucpress.com