On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks

Simon Garfield

Gotham

Buy

Maps are handy devices for getting us where we're going, whether to a friend's house in the next town or a new job posting halfway around the world. According to clichés, women can't read them, but men rely on them to avoid asking for directions. At any rate, maps are basically just tools.

In the hands of the British journalist and author Simon Garfield, however, they are symbols. The same way that Garfield made printers' fonts a window into culture and emotion in Just My Type, now in his newest book - On the Map: A Mind-Expanding Exploration of the Way the World Looks - he looks at the many paths where maps can lead us. They are reflections of the politics, culture, religion, trade patterns and economic power of the country where they were drawn - sometimes works of art, sometimes whimsical, sometimes aids to public health, sometimes meant to give moral direction rather than the miles-and-metres kind.

"To know about maps," he says, "is to know one's place in the world."

It's a clever concept, and the book offers lots of fascinating titbits along the route. Garfield writes in an easy style with splashes of wry humour. Still, he hasn't found 464 pages worth of intriguing things to say about maps. Inevitably, he ends up overemphasising trivial points and overwhelming the reader with examples.

The book starts with the earliest maps, some of which are rather cute in their mistakes and assumptions, and some of which were amazingly accurate.

"By the fifth century BC, Pythagoras had argued persuasively that the earth was a sphere," Garfield writes, and the Libyan scholar Eratosthenes 200 years later calculated the globe's circumference to within 100 miles (160km). (He estimated 25,000 miles rather than the actual 24,901.55.) Ptolemy's atlas, written in the second century AD, "changed the way we looked at the world so fundamentally that - almost 1,350 years later - it was, in modified form, one of the main navigational tools Columbus carried with him when he departed for Japan in 1492."

Slowly, over the next two millennia, the charted world took clearer shape. The Western Hemisphere, Australia and the poles were added, of course, and the three known continents of Europe, Asia and "Libya" were updated as well. Asia grew east, beyond India; Japan and China switched places; England moved into its proper location; Africa stretched south and its coastline was slowly filled in.

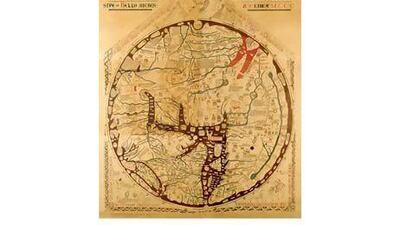

Even as they became more realistic in certain ways, some of the maps branched out into fantasy. They featured tourist attractions that just don't exist, such as the Garden of Eden, the landing place of Noah's Ark, and sites from TheOdyssey. On the 13th-century Mappa Mundi of Hereford in Britain there is "the sciapod - a man deploying his single swollen foot to shield himself from the sun". A German map from roughly the same time included an African population without noses or mouths and "a nation with upper lips so elastic that they may pull them over their heads for disguise and shelter".

On the other hand, the author disposes of one map-related myth: "The phrase 'Here Be Dragons' has never actually appeared on a historic map" to indicate medieval terror of what lay beyond the edge of the flat world, he writes. The closest parallel might be the Latin phrase Hic Sunt Dracones on a small, 16th-century globe, possibly referring to dragons in China.

Clearly, reading about such artefacts is much more fun than deciphering an ordinary map. Garfield even provides illustrations, although the reader is advised to keep a magnifying glass handy.

As the book points out, however, the fun has a serious side. Most medieval maps - whether drawn by European Christians, Arab Muslims, or Asian Buddhists - "were not intended for use, at least not for travel use", according to Garfield. "Rather, they were statements of philosophical, political, religious, encyclopaedic and conceptual concerns." Hence, the reminders of the lost Eden and the salvation of Noah.

Perhaps most bizarre was the German map with the weird African people, which also included an outline of Jesus's body, positioned as if on the cross, and "splayed out … so that it grasps the whole of the world". The map literally portrayed "the concept of Christianity embracing all humanity".

But if those maps began with a religious message, politics eventually took over. Mapping became a powerful tool of imperialism; whoever controlled the pen could control the boundaries.

When Britain surveyed India from 1802 to 1818, using the most modern techniques of triangulation, Garfield writes, "it consolidated British influence wherever a theodolite [an instrument for measuring angles] and trig point was placed, and the East India Company, the survey's initial sponsor, took full advantage in claiming new territory under the guise of scientific progress".

In a different way, by leaving wide blank spaces in Africa, European cartographers of the 1700s and beyond "made huge political suggestions: the continent, universally known for its troves of slaves and gold, is wide open for conquest". During the 20th century, activists would protest that the classic Mercator projection - the one, still used today, that allows the three-dimensional globe to be spread accurately on two-dimensional paper - was biased because, by the very way that it stretched out the globe, "it over-emphasised the size and significance of the developed world at the expense of the underdeveloped".

Mapmaking has also been a function of the economic, naval, artistic and trading prowess of the nation where the mapmaker lived, as well as "the ability and willingness of monarchies to commission new explorations". Thus, Italy turned out beautiful charts in the 1400s because its printing ability was advanced. Germany, France, Britain, the Netherlands and Belgium would all have their turns.

And maps can do more than paint the wide world. This book presents a parade of odd and pinpoint maps, such as the 19th-century demographic map of London that coloured streets according to their income and crime levels. Laid out so clearly, the map's sociological revelations led to the creation of Britain's first pension system.

Today's mapping pioneers, the author contends, are the creators of video games, where intricate quests and escapes rely on digitally mapped routes.

In addition to these big thematic pictures, Garfield is good at describing the nitty-gritty work that goes into mapping. Surveyors spent years traipsing the English countryside with their theodolites and other tools, while explorers in Antarctica tried to draw with half-frozen fingers "so cold that you don't know what or where they are".

However, one of the book's weaknesses is that the author fails to transfer this descriptive power to the open seas, to explain how the voyages of the great explorers like Columbus, Drake and Da Gama enabled Europeans to make more accurate world maps. All he really says is that captains generally noted their coordinates, but that only told where the ship was, somewhere out in the water. Did crew members, or the captains themselves, also sketch out rough maps of the coastlines? Did they write descriptions? What about the huge expanses of land and sea that no explorer ever got near: how did those get tracked, centuries before ocean liners and air travel?

Moreover, the book skims too lightly over the potential privacy violations in combining digital mapping, smartphones, GPS, Wi-Fi, and the rest of the e-world.

But the biggest problem with On the Map is that there are just too many maps. Even before the halfway mark, the reader is growing confused and, frankly, bored.

Garfield's obvious enthusiasm for his subject actually makes the situation worse. Everything seems to be a breathless "first", "best", or "most". Joan Blaeu's Atlas Maior, published in Amsterdam in the 17th century, "was quite simply the most beautiful, elaborate, expensive, heaviest and stunning work of cartography that the world had ever seen". However, the 1953 World Geo-Graphic Atlas, published in Chicago, "is regarded by many as the most beautiful and original modern atlas ever made".

There are also "the first printed map to show the Gulf of Mexico", "the first printed world map to show Greenland", "the first example anywhere of a map overlaid with sound", "the first commercially produced forensic murder map", and many more minor or even significant ground-breakers. Moreover, Garfield places far too much significance on the use of maps in a few movies.

But such an analysis may be unfair to this book. After all, no one reads the index to a map word for word. So perhaps On the Map should be treated like one - to be picked up from time to time when a reader just wants to get to one particular point, like an explanation of Mercator's projection or an answer for a trivia game.

This book will probably get readers where they need to go, and the ride will be a pleasure.

Fran Hawthorne is an award-winning US-based author and journalist who specialises in covering the intersection of business, finance and social policy.