Archaeology from Space: How the Future Shapes Our Past is a well-written, engaging gem of a book that invites even the most casual readers to understand pioneering Egyptologist Sarah Parcak's revolutionary work.

"I'm part of a relatively new specialism called space archaeology. I am not making that term up," she writes early in the book, anticipating the scepticism or misconceptions she imagines laypeople might have when attempting to understand her work.

In another segment, Parcak humorously recounts how she received an unrealistically high quotation for travel insurance before a summer she was due to spend at an excavation site. The explanation she received after further inquiry was that the insurance team mistakenly believed she would be travelling into space to look down to ancient ruins from the physical satellites. Much to the chagrin of readers who initially might mistakenly think the same, Parcak debunks false perceptions of her profession.

In fact, much of Parcak's work seeks to empower everyday people to understand archaeology as well as the role of satellite imagery in studying ancient civilisations. However, a multimillion-dollar Nasa space suit isn't quite part of the required gear.

In 2016, she was awarded a Ted Prize worth $1 million (Dh3.67m) to build an "online citizen-science platform" that the public can use to participate in the process of archeological exploration, thereby protecting cultural heritage, in particular "hidden heritage". Launched in January 2017, the platform GlobalXplorer.org uses satellite technology to democratise the process of mapping ancient sites, enabling almost anyone with an internet connection to become, as Parcak puts it, a "stakeholder in how history gets written".

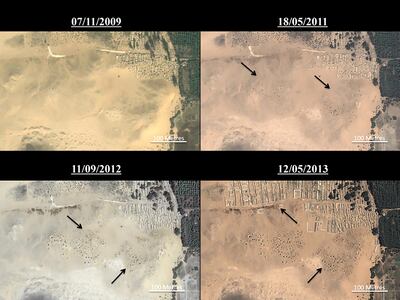

Parcak's book also reveals the crucial role satellite imagery has played in exposing looting of archaeological sites. She herself witnessed the wide-scale looting south of Giza in Egypt after the 2011 Arab uprisings through remote-sensing technology. Parcak and her team often use Google Earth open-access data in their work as well, since commercial satellite data often cost millions of dollars for large-scale projects. While examining high-resolution imagery spanning the years 2002 through to 2013, they realised that the looting significantly increased in the years after 2008, attributing it to the global recession as opposed to the region's political unrest a couple of years thereafter.

Through this work Parcak is able to forecast prospective trends. "Our conclusion is that if nothing is done, by 2040, all of Egypt's sites will be affected by looting. Our global archaeological heritage has a serious problem … If archaeologists and other experts do nothing to combat these issues, most ancient sites in the Middle East alone will disappear in the next 20 to 25 years."

Archaeology from Space also reveals Parcak and her counterparts' impressive global discoveries using aerial and remote-sensing technology, including a University of Helsinki-led find of a "new" civilisation dating between 200 and 1283 AD in Acre, western Brazil and ongoing research by a University of Leicester team in Tunisia and Libya uncovering the "lost" civilisation of the Garamantes.

"I think Africa represents the greatest frontier for archaeological discovery in the world," she writes in a segment where she argues that the world's second-most populous continent is "ripe" for exploration. It echoes the much hashed-out sentiment, usually voiced by economists, that the future is African. But Parcak is no Orientalist – towards the end of the book, she overturns a common unfounded belief that extraterrestrials might have built Earth's most prominent architectural monuments, instead referring to overlooked contributions by minorities. "Inane alien theories … unfortunately still hold wide appeal for those who cannot accept that people of a different skin colour created monuments lasting millennia," she says.

Parcak's work extends from the past to the future, too. Not only does she study preserving heritage – she also strongly feels there is much to learn about the future by understanding antiquity. Climate change and rampant urbanisation, for example, have led to the destruction of ancient sites across the globe, and studying this is crucial to further understanding how ancient civilisations thrived and collapsed because of similar factors, she argues.

From the so-called Little Ice Age of medieval times to the demise of Ancient Egypt's Old Kingdom, the factors leading to decreasing resources, famine and a consequent mass decline of livelihoods could sound all too familiar to a modern-day reader.

Thankfully, Archaeology from Space is a particularly compelling read because it avoids being a dry historical or scientific text. Besides her notable contributions to archaeological exploration – a field notorious for often being dominated by white men – the acclaimed academic also has a gift for storytelling. In the book's first couple of chapters, she draws the reader in by describing how Indiana Jones and her grandfather's work as a forestry professor, among other influences, inspired her career as an Egyptologist. In another chapter, through a fictionalised narrative of a woman growing up during the collapse of Egypt's Old Kingdom, Parcak brings to life the little-known settlement of Tell Ibrahim Awad in Egypt's north-east Delta.

Parcak's book is compelling not only for informing readers of the significance of her work and future possibilities of using technology for archaeological discovery, but also for her humour and gripping chronicling. This all works together to create a unique, recommended page-turner.