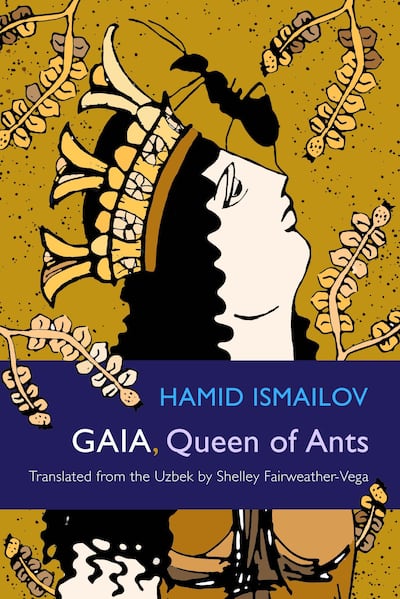

Reading Uzbek author Hamid Ismailov's latest novel, Gaia, Queen of Ants, translated by Shelley Fairweather-Vega, is like falling head first into a cauldron filled with a rich blend of mythology, Sufi fables, politics, various cultures and humour.

Published only one month after the release in English of Ismailov's Of Strangers and Bees, also translated by Fairweather-Vega, this novel recounts the lives of three characters living in exile in contemporary England and France, all searching for their place in the world. While Of Strangers and Bees also speaks of exile, it reaches back in history to imagine the fate of Avicenna, the great philosopher and scientist of the medieval Islamic world who was born in Bukhara, in what is now Uzbekistan.

In Gaia, Queen of Ants, none of the characters are Uzbeks, even if they lived in or are passing through Uzbekistan. The vast area of Central Asia, with its colloquially known "stans", is such an impressive mix of cultures, languages and religions, given its location along the Silk Road and its history of having a Persian, Turkic, Russian, then Soviet presence, that the notion of cosmopolitanism takes on a whole new meaning.

Ismailov, who was born in what is now Kyrgyzstan, narrowly escaped being sent to Bukhara by his father's family to study Islamic theology. His mother, who had a Soviet education, left his father and moved with the young Ismailov to Uzbekistan, but died when he was 12. He was brought up by his grandmother, who was from a noble Uzbek family, and who made him read classical poetry and One Thousand and One Nights to her.

"I hated it," Ismailov tells The National. "At 12 you want to play football. But it was my obligation."

Clearly the seeds of literature were planted during his formative years. "But they only flourished much later when I was in my thirties and I returned to the classics."

As an adult, Ismailov lived in Tashkent and then in Moscow, where he championed Uzbek literature for the writers' union.

During the Soviet era he translated Uzbek classics and works from Farsi into Russian, as well as translating western and Russian classics into Uzbek. He wrote poetry that was "too decadent, not upbeat enough to be published".

When Uzbekistan declared its independence in 1991 as the Soviet Union collapsed, Ismailov was accused of fomenting trouble by Islam Karimov, then the country's leader. So in 1994, Ismailov moved to Britain, where he was been ever since, working for a long time at the BBC World Service.

Ismailov's first books were written in Russian. Of Strangers and Bees was the first he wrote in Uzbek, having worked on it between 1998 and 2000. A French publishing company, L'Harmattan, published it in Uzbek with funding from George Soros's Open Society Foundations, which also helped to smuggle the book into Uzbekistan and distribute it, Ismailov says, as his books were banned by the state.

Making the switch from writing in Russian to Uzbek was gradual, blossoming slowly inside of him. When he lived in Uzbekistan, he says he "was dealing with western literature and I was less interested in Uzbek literature. Then in Moscow I realised we had turned into 'nationalists' and it was time to appreciate our roots."

He says he is "connected to Uzbek culture much more deeply than those who tried to take it away from me. It was inbuilt in my family. I had translated so much Sufi poetry into Russian".

Only one of his books written in Uzbek has been published in his home nation and that was done samizdat style, which is a way of copying and distributing literature banned by the state. The book, The Devils' Dance, has Uzbek writer Abdulla Qodiriy as its hero, a man who died during Stalin's purges in 1938, and the work was originally published chapter by chapter on Ismailov's Facebook page.

"When president Karimov died in 2016 the chapters were put together and the book was sent to print without my knowledge or consent," says Ismailov, who sounds pleased, nonetheless. The Devils' Dance, translated into English by Donald Rayfield and John Farndon, won the EBRD Literature Prize this year.

In Gaia, Queen of Ants, Ismailov introduces the reader to the scheming Gaia Mangitkhanovna, who has a questionable past linked to powerful politicians. Although she is now an old woman living in exile in Britain, her gaze, under swollen lids, remains piercing, with "diamond eyes", as her life intersects with Domrul's, a naive young Meskhetian Turk from Uzbekistan who fled to Britain as a child following ethnic purges. His spoken Uzbek is "a bit bookish, a little bit of pasture grass mixed in with the rice".

Now in the "twilight of her life", Gaia is plotting her own death and intends to use Domrul to help her. Ismailov says she acts in the manner of "Iron Ladies, many of them brought up during Stalin's time, who control everything, including their own death; they leave nothing to chance".

Domrul considers himself a "modern-day Muslim" who follows the Naqshbandi Sufi order, while his girlfriend, Emer, is Irish, but grew up in the Balkans. Both are named after characters in Turkic or Irish folk tales and "represent different strands of mythologies and the clash of narratives," Ismailov explains.

As readers discover, there are many strands, intersecting and then separating again. The publication of this highly readable, smoothly translated novel, is one more victory in the struggle to see more Central Asian literature in translation. "During Soviet times, this literature was present," said Ismailov. "We have many wonderful writers but not many now pay attention to them. Maybe somehow we can make a difference."

Part of the problem is the dearth of Uzbek to English translators. Ismailov has two translators, Fairweather-Vega, and Rayfield, who translates Russian and Georgian to English and taught himself Uzbek to translate The Devils' Dance. A translator himself, Ismailov says he only realised how difficult his writing was to translate when he received from Rayfield a draft of his next book, Manaschi, which refers to a person who recites Kyrgyz literature's the Epic of Manas.

"Uzbek is a formalised language," Ismailov says. "The challenge is to break the narrative and make a mess of it. It's literary maths that takes you to an unknown place. You are immersed in this and aren't considering your translator. Luckily, I speak English and we unravel the catacombs of my sentences together."