"Poems are heart and soul made legible," wrote Elizabeth Alexander in the foreword to 2017's How Lovely the Ruins: Inspirational Poems and Words for Difficult Times.

Here, American poet Alexander refers to the art form's ability to express the things that roil and rage within us. Throughout history, words and verses have been used by everyone with a message to share – from lovers to activists, from prisoners to politicians. Poems – and the poets who write them – have a way of uplifting, empowering, sobering and humbling us with only a few lines.

As we live through challenging times, here are seven poems that contain hope and carry reminders for us to stand up to struggles instead of giving into them.

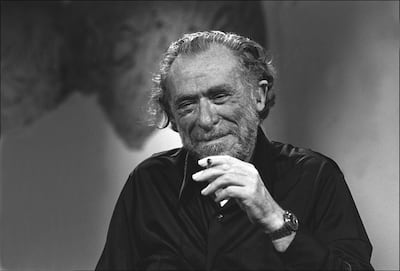

The Laughing Heart by Charles Bukowski

“Your life is your life

don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission.

be on the watch.

there are ways out.

there is light somewhere.

it may not be much light but

it beats the darkness.”

A prolific writer, Bukowski created poems brimming with machismo and violent imagery. His life was equally rough, surviving childhood abuse and battling addiction as an adult. But there is an honesty and directness to his work that continually draws readers, and there are shining moments of hope in his words, too. The Laughing Heart is a straightforward directive to make our way out of the darkness.

Kindness by Naomi Shihab Nye

“Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside,

You must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.

You must wake up with sorrow.

You must speak to it till your voice

catches the thread of all sorrows

and you see the size of the cloth.”

Born to a Palestinian father and American mother, Nye has lived in Jerusalem and Texas. Her poems reflect this cross-cultural upbringing with their emphasis on diversity and connection. In Kindness, Nye writes about compassion as something that is forged during hard times. The poem begins with the line: "Before you know what kindness really is / you must lose things." It is only when we understand loss – your own and that of others – that kindness can truly take root and become part of our daily lives.

I Worried by Mary Oliver

“Finally I saw that worrying had come to nothing.

And gave it up. And took my old body

and went out into the morning,

and sang.”

Pulitzer Prize winner Oliver sees into our lives so clearly and then relates these observations to us in moving, incisive, uncomplicated prose. For many, her poetry collection Devotions serves as a kind of manual for life with its explorations of loss, mortality and how to navigate the ups and downs of existence. Oliver, who died last year, began writing poetry about nature and evolved to more personal verse with a more spiritual dimension.

The Peace of Wild Things by Wendell Berry

"When despair for the world grows in me and I wake in the night at the least sound in fear of what my life and my children's lives may be, I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds."

It is no surprise that poet and environmental activist Berry's poems bear so much reverence for nature and its restorative effects. His poem The Peace of Wild Things refers to the beauty of animals, which do not burden their minds with worry or the "forethought of grief". Alongside his writing, the American author has also been outspoken about issues such as nuclear power and coal mining.

Now That We Have Tasted Hope by Khaled Mattawa

“Now that we have come out of hiding,

Why would we live again in the tombs we’d made out of our souls?”

Born in Benghazi, Mattawa moved to the US when he was a teenager. In his poetry, he has addressed the migrant crisis with piercing descriptions of the struggles of refugees. Mattawa has also translated the poems of Adonis and Fadhil Al Azzawi into English. Mattawa's poem Now That We Have Tasted Hope is a powerful declaration of a new way of life with political undertones. The speaker proclaims to have crossed a threshold into freedom, one that he cannot walk back from: "Now that we have tasted hope, this hard-earned crust, / We would sooner die than seek any other taste to life, / Any other way of being human."

Perhaps the World Ends Here by Joy Harjo

“The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat to live.

The gifts of earth are brought and prepared, set on the table. So it has been since creation, and it will go on.”

Part of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in the US, Harjo weaves First Nations histories as well indigenous narratives and myths into her writing. Her poetry tackles ideas of justice, feminism and the importance of remembering the past, whether it is the legacy of colonialism or the strength and survival of your ancestors. Her poem Perhaps the World Ends Here builds on central metaphor for our lives, encompassing the small and sweeping events that come to define it. It ends with a note of gratitude for all we have to experience and endure: "Perhaps the world will end at the kitchen table, while we are laughing and crying, eating of the last sweet bite."

Good Bones by Maggie Smith

“…The world is at least

fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative

estimate, though I keep this from my children.

For every bird there is a stone thrown at a bird.

For every loved child, a child broken, bagged,

sunk in a lake. Life is short and the world

is at least half terrible, and for every kind

stranger, there is one who would break you,

though I keep this from my children.”

Ohio-born Smith's Good Bones was a hit in 2016. It made the rounds online and was even used in an interpretive dance number in India. The speaker in Smith's poem has no illusions about life. She knows its difficulties ("fifty percent terrible"), but still tries to shield her children from these realities. Despite her list of criticisms, she holds out a little hope – comparing life to a house with "good bones" or a solid foundation that can be turned into something great.