For Zeina Hashem Beck, one letter can contain a multitude of meaning. The Dubai poet's latest collection, which will be published by Penguin Books in 2022, is simply titled O.

“‘O’ is the main vowel in so many keywords in this collection – odes, joy, love, body, mother, god. We also use ‘o’ for wonder; ‘o’ for pause; ‘o’ as an opening to something else, or something infinite,” she says.

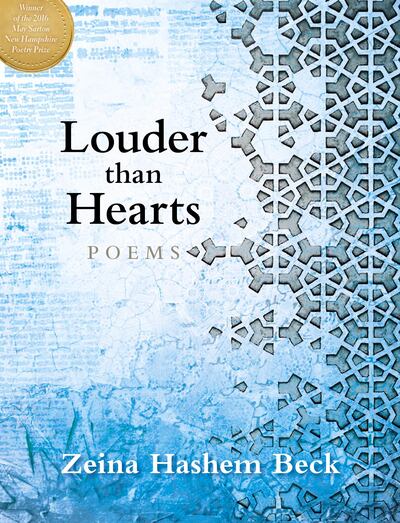

The book is a big step for Beck, securing the poet her first major publisher. Her most previous book, Louder than Hearts, was published by Bauhan Publishing in 2017, and her earlier chapbooks by small, independent publishers in the UK and the US.

Born in Lebanon, Beck grew up in Tripoli in the 1980s as the country was gripped by civil war. Though she does not have vivid memories of the violence then, she experienced the anxieties and disruptions that war brought. It was only when she moved out of Lebanon in 2006 that she began to consider publishing her poetry. With her husband, she lived in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain before moving to Dubai in the early 2010s.

While the burden of loss and conflict may be imbued in her writing, Beck sets down these themes through narratives, personal stories and memories in a distinctive voice marked with lyricism and quotidian imagery.

Louder than Hearts won the 2016 May Sarton New Hampshire Poetry Prize and carries stories of war and displacement, broken up by more hopeful poems about religion and faith.

For O, Beck says the theme “focuses on the body as a physical entity, but also as a political entity; the body in its profanity and divinity. It has motherhood, love and longing, friendship and language.”

The collection gathers a number of unpublished poems and those that have been published in literary magazines over the past three years, and presents them together for the first time. It includes some from her duet series, which fuses Arabic and English on the page.

Her poems have often incorporated Arabizi, which transliterates Arabic words and numerals in Latin script, but her “duets” embodies a new experimental form developed by Beck three years ago. Instead of interspersing Arabic lines into English, where the former would be a translated repetition of the latter, the poet juxtaposes different verses and entire poems with each other. “You have these two languages on the page, and they both exist separately and in relation to each other,” she explains.

“You have these two languages on the page, and they both exist separately and in relation to each other,” she explains.

In many ways, language signifies identity, too. Beck’s education was primarily in Arabic and French, though most of her poetry is in English and is distributed to western audiences. But while the weaving in of a foreign language to western readers may be seen as an alienating step, Beck uses it as a declaration of her own personhood: “It was inevitable for Arabic to seep into my poetry because it is who I am. I have to write like me. I’m a person at the intersection of languages,” she says.

The “duets” will appear in O, along with her contemporary take on the ghazal, an ode in Arabic poetry relating to romantic love and loss.

A recurring theme in her poetry, motherhood “takes up more space” in the coming collection, Beck says. The figure of the mother has taken on many shapes in her work, whether it is the unflinchingly resilient speaker in the poem Flamingos, in which a woman with a sick child sets aside her own injury to care for her daughter, or the mothers and women in There Was and How Much There Was, who gather and gossip about family, film and faith.

It was the poet’s own experience with motherhood that crystallised this character, but in Beck’s poetry, motherhood is also a vehicle that takes her down pathways to other ideas. “I’m interested in what we inherit from our mothers, and our mothers’ mothers on a conscious and subconscious level – they pass joy, they pass trauma. I’m really interested in how these stories are passed on from mother to daughter.”

Beck has two daughters, aged 10 and 12. “The word doesn’t just mean the physical mother, but also mother tongue, motherland, what is home for those who keep travelling, and so on,” she says.

As she looks ahead to the editing process with Penguin Books, Beck says her hope is that when it is published, “the book finds its way to readers who love it”.

'O' will be released in the summer of 2022