Death at Sea World

David Kirby

St Martin's Press

Picture the scene: you're kayaking in the north-east stretch of Johnstone Strait, which runs along the coast of Vancouver Island in British Columbia. It's early morning, and a thick mist still hangs over the water, almost obscuring the steep rows of trees along the mainland shore. There is no sound but the gentle splashing of your own passage; even the seabirds are quiet, and the near-freezing water is as smooth as glass. Everything seems peaceful, and yet, unseen by you, the strait contains massive, knotted potentials of some of the worst violence imaginable anywhere at sea.

Then, with eerie silence and smooth assurance, a dark fin splits the surface 10 feet from your kayak - and it grows, climbing higher and higher out of the water until it towers over where you're sitting. You see streaking forms now rising in the water, flashing white highlights you belatedly realise are all part of one vast body. Then another fin, then another, and the morning quiet is broken by quick, deep exhalations that mist in the chilly air. A pod of killer whales (Orcinus orca) has surfaced all around you.

Maybe there are six animals, maybe 10. You notice the almost overpowering muscular ease with which they power through the water. The adults are gigantic - six metres long and barrel-massive - and perhaps you notice smaller forms among the giants, calves being patiently shepherded along. The pod unhesitatingly moves on, giving you no attention whatsoever. There is none of the playful curiosity a visiting dolphin might show, and none of the opportunistic malevolence you might get from a big shark. Instead, the always-reported feeling is one of complete indifference: these are great finished animals, apex predators, on their way from one point to a distant other point, fearing nothing, constantly bombarding each other with calls and clicks and whistles, paying no more attention to you than you would to the dawn hunting dramas being played out by commuters on the roads. Two separate worlds, you might think, and the whales' indifference would be so consummate in the few minutes they were with you that you wouldn't even remember to be afraid.

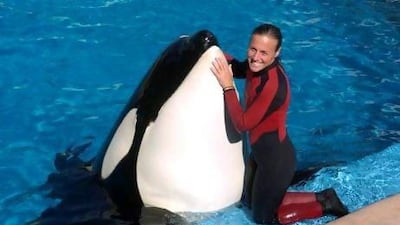

To go straight from that moment to the crowded stands at any SeaWorld, where cheering adults have paid US$70 (Dh257) apiece to watch captive killer whales wave at them and jump on command, is to flatly confront a quintessential wrongness, the same feeling any African trail guide will tell you about when seeing a circus elephant shamble into the centre ring dressed in clown slippers. There is a momentary thrill at seeing such an enormous creature up close; the sense of sheer power broadcast by adult killer whales far exceeds that of any living thing most audience members are

ever likely to see in their lives. But that thrill comes at a substantial price to the animals involved - and sometimes to the humans as well.

That price is at the heart of David Kirby's relentless, angry reportorial jeremiad Death at SeaWorld. Kirby is a veteran investigative reporter who's been probing the real stories behind the dozens of incidents over dozens of years that SeaWorld invariably describes in nonspecific terms like "incident" and "accident". No representative of SeaWorld's three US locations spoke with Kirby on the record, but plenty of current and former employees did, and the composite picture he creates from all these sources is horrifying. This is a warning-bell book on par with Upton Sinclair's The Jungle or Jessica Mitford's The American Way of Death.

In the wild, killer whales live in tight-knit strictly matriarchal extended family groups characterised by highly specific vocalisations (varying from region to region and even from pod to pod), constant predation and constant movement through a varying environment. Rough scientific data suggests that their average lifespans measure to roughly that of humans, 60 to 70 years. In captivity, killer whales spend large amounts of time in small isolated concrete tanks of empty water, cut off from all stimuli and all family. They of course cannot hunt - they're fed more than 100kg of food every day, much of it laced with vitamins and medication. The whales, Kirby says, often sensed these additions and "would sometimes spit out the spiked food". They were also fed slabs of a gelatin mixture designed to keep them hydrated. And deaths before the age of 20 are common.

Even with financial records as carefully guarded as those of SeaWorld, it's obvious the parks gathered large ticket receipts from the exhibition of these creatures. SeaWorld is required by law to make at least a pretence of educating the public about the physiology and natural history of the killer whales it uses in its shows, and in the absence of the park's own attempts to defend itself, Kirby's readers are left with an utterly damning portrait of a company skilled in the use of "verbal ju-jitsu" to deflect awkward questions from both the ticket-buying public and curious marine biologists.

Kirby boils down his inquiry to two related questions: "Is captivity in an amusement park good for orcas? Is this the appropriate venue for killer whales to be held, and does it somehow benefit wild orcas and their ocean habitat, as the industry claims?" and "Is orca captivity good for society: Is it safe for trainers and truly educational for a public that pays to watch the whales perform what critics say are animal tricks akin to circus acts?" The irresistible arc of his story makes it clear that the answer to all those questions is no. Wild orcas live much longer, more varied and more emotionally satisfying lives in the wild than they do in captivity, where almost always confined, listless, and separated from their own family members. The public is given virtually nothing in the way of real education during the killer whale shows (in one withering aside, Kirby notes that the crowds are exhorted by poolside trainers to follow Shamu's 'posts' on Twitter).

And then there's that part about the safety of the trainers. This is the heart of Kirby's book - the incredible fact that for decades, human trainers have spent two shows a day diving into the water with these confined behemoths. From the very beginning, there was entirely predictable trouble. On February 20, 1991, at SeaLand of the Pacific, just outside Victoria, British Columbia, that trouble turned deadly: trainer Keltie Byrne, a seasoned swimmer and athlete, slipped on the narrow walkway separating the main whale pool from the stands. Her leg dipped into the cold water of the tank - and one of the three killer whales in the tank at the time, an enormous bull male named Tilikum ("the friendly one" in one of the book's countless grim ironies), instantly seized it and pulled Byrne into the water. While the young woman screamed, Tilikum thrashed her around in an attempt to keep her away from the tank's other occupants, two dominant females named Haida II and Nootka IV. But all three whales cooperated to keep Byrne from leaving the pool - they intentionally kept her out of reach of rescue-poles extended by her terrified co-workers. It was over two hours before trainers could get Tilikum to relinquish her body.

SeaLand sold Tilikum to SeaWorld in Orlando, Florida, with understandable alacrity.

Eight years later, a man hid from SeaWorld authorities and entered the whale pen at night. In the morning, trainers found Tilikum playing with his naked and damaged body.

But at 6.7 metres long and more than 5,000kg, Tilikum was a genuine star attraction, so he continued doing "water work" in close proximity to trainers. Those trainers knew by this point never to enter the water with this whale, but they couldn't retire him either.

A breaking point of sorts - and the starting point of Kirby's animus, one senses - happened on February 24, 2010, when 40-year-old veteran SeaWorld trainer Dawn Brancheau was finishing up a show with Tilikum and other orcas. Tilikum seized Brancheau, pulled her into the recesses of the pool, crushed her in front of screaming tourists, and again refused to relinquish the body. Kirby flatly asserts that this was an act of intentional murder, not an inter-species misunderstanding, and whether he's right or not, the incident at first seemed to change everything. Regulatory bodies such as the Occupational Safety and Health Administration concluded that the only way to eliminate the risk was to prohibit the activity, and SeaWorld was fined.

Not all experts agree with a finding of wilful murder. "Tilikum is a casualty of captivity; it has destroyed his mind and turned him demented," claimed Russ Rector, a former dolphin trainer who ran the Dolphin Freedom Foundation in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. "If he was a horse, dog, bear, cat, or elephant, he would already have been put down after the first kill, and this is his third."

The industry continues. Trainers are back at work, and so is Tilikum, doing his shows every day to rapturous applause. No reader of Death at SeaWorld will be able to think about the whole situation without wondering who'll be the next trainer to slip on a slick dividing wall, or get in the water with the wrong animal in the wrong mood, or even just not lunge out of the way fast enough. After Kirby's brutal and ground-breaking work, we can't say we weren't warned.

Steve Donoghue is the managing editor of Open Letters Monthly.