The classic images of the American “Wild West,” of horse towns, savage yet beautiful landscapes and dastardly bad guys, are hardwired into global literature and cinema. We all grow up with romanticised tales of the frontier, where buffalo, Native Americans and, more pertinently, sharpshooting settlers roam. For novelist C Pam Zhang, who was born in Beijing but moved to America when she was four, it was no different.

“I loved the gilded swagger of the American West, the image of those cowboys and frontiersmen who lived so large,” she says.

It was only later that she learnt about the violence and bigotry that made westward expansion possible. “The paradox of that mythology is alluring to me,” she says. And so she set about creating her my own mythology of the Wild West, one that featured the grit and beauty of people like her.

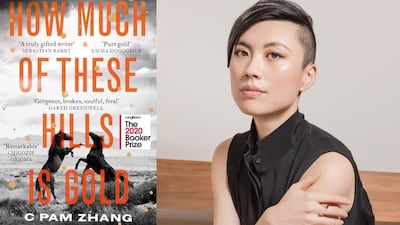

The result is her sensational debut How Much of These Hills is Gold, and on Tuesday, September 15, she will discover whether it has made the leap from the Booker Prize longlist to the final six. The judges called it a "haunting and heartbreaking story of two immigrant children coping alone amid the fading leftovers of the Gold Rush in 19th century California." And the book certainly speaks clearly and timelessly of the immigrant experience, of loneliness, isolation and dislocation.

Every immigrant story is epic in scope

Its “heroes”, Lucy and Sam, are of Chinese descent, and begin their adventure having to drag their father’s rotting corpse away from a hostile town, to find a place to bury him. Zhang thinks that every immigrant story is epic in scope, and this book certainly feels like a tribute to anyone who has had to search for home, just as her family did.

Right from the epigraph – “This land is not your land” – Zhang cuts through the idea of the American Dream, where there is ample and equal opportunity for all. “The playing field isn’t level for an immigrant, a person of colour, a person of familial wealth,” she says.

“And that first line was a flag planted in the ground; there are no easy answers about land ownership in the book, as there are no easy answers today. I mean, how do you not feel conflicted as a white American whose ancestors stole the land through the bloodshed of indigenous people, or as an indigenous person seeing your people’s disenfranchisement, or as a Black person whose ancestors were forcibly brought over? Or as a Chinese child of immigrants who hears 'Go back to your country,' despite growing up in this country?

“For better or worse we must all live with these conflicted feelings.”

'Imagining lost histories'

Zhang was keen that How Much of These Hills is Gold wasn't too firmly anchored in the specific realities of the Chinese-American experience, most obviously because she has tigers magically roaming the land, too.

True, more than 15,000 people from China did come to work on the Transcontinental Railroad in the 1860s, the completion of which is captured in the book through the eyes of Lucy as “a picture that shows none of the people who look like her, who built it.” But Zhang was more interested in representing stories of marginalised people generally, be that because of race, gender, sexuality or identity, which is why her debut feels so universal.

“They’ve been deliberately repressed or excised from written history. We will never recover them, and that is a tragedy. So the work of an artist is to use empathy and craft to imagine those lost histories. We can recover, if not the facts, then some of the emotional truth."

And that emotional truth is most raw in the way the book explores grief. Zhang, too, lost her father when she was in her early twenties, and though we don't speak of that experience directly (she is now 30) the lasting effects of mourning, or indeed not finding peace with grief, are haunting in How Much of These Hills is Gold.

“Thank you for noticing that,” she says. “This aspect of the novel tends to get overshadowed by the adventure story, or the family story, or the Wild West setting. Grief and a kind of long-held ache underpin this novel. Grief for the dead father, the missing mother, for childhood, for a ravaged landscape, for all of it. It was important to me to put that grief next to power and beauty. It’s impossible to consider the landscape of Northern California, burning as it is with wildfires, without thinking of everything we have lost or will soon lose.”

Where is home for her?

The characters in Zhang’s novel ultimately find solace and sanctuary in a harsh landscape and wildness – which is in a strange way more predictable for them than the actions of man.

“But I’m terrified of nature!” she jokes. “It’s beautiful and deadly and insensate to human desires, which is precisely why it is important. Mostly I stand in awe of the natural world. I know I am unfit to survive out there. It seems to me an act of profound arrogance to feel totally comfortable in the wilderness. But that vibration between fear and awe is one engine of the book. As a writer, I believe in plumbing my fears. I write into what is scariest and strangest in order to find what is original.”

“The nuance for Asian-Americans like Lucy in the book is that there exists the tantalising idea that you may be allowed to assimilate into whiteness,” she says. "It’s a lie, but the false hope makes Lucy even more opaque to herself. For me, more and more, I find beauty in liminal spaces, in a state of ambivalence. Which is probably the best way to describe this wildly unpredictable book. Whether it makes it to the Booker shortlist is almost irrelevant because the work of a woman who, as the jacket puts it, “has lived in 13 cities and is still looking for home”, is an achievement as epic as the scope of any immigrant’s story. So does she feel San Francisco, or even America itself, is finally, some kind of home?

“So yes, it may be an impossible question to answer if one expects the answer to be one town, one place. But maybe the answer can be more expansive these days.”