Fractured Times: Culture and Society in the 20th Century

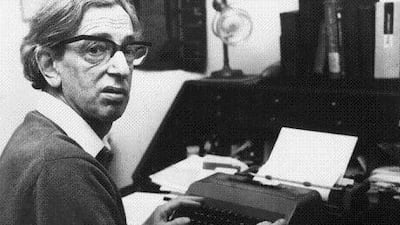

Eric Hobsbawm

Little, Brown

Few historians could claim to be a bestseller from Brazil to Bombay, but such was the renown of Eric Hobsbawm. Famed for his trilogy of works on the "long 19th century" (1789-1914) and its companion volume, The Age of Extremes, which covered the "short 20th century" (1914-1989), Hobsbawm wrote history for the "educated non-expert", as he once put it. This he did superbly.

Hobsbawm was also famous - to some, infamous - for his lifelong allegiance to the Communist Party. Long after most western intellectuals abandoned the movement, Hobsbawm stayed on. "The dream of the October Revolution is still there somewhere inside me," he declared at the beginning of the 21st century. (As if on script, Hobsbawm was born in 1917, and died in October last year.) Until the end of his life, his detractors huffed and puffed, and demanded he account for such ideological perversions. Hobsbawm merely shrugged.

Yet Hobsbawm was hardly a doctrinaire leftist. His historiographical instincts, while Marxist, were, with a few glaring exceptions, canny and often profound. In his trilogy, he made sense of a century-plus of European war, revolution, economic growth, imperial conquest and capital accumulation. He wrote history with a sociological bent, breaking down the past into patterns, categories and social types. One of the great characters in this unfolding tapestry is the bourgeoisie. Part hero, part villain; part creator, part destroyer, this striving social class created a culture whose confused legacy remains to this day.

In his final book, assembled shortly before his death last year, Hobsbawm ponders "what has happened to the art and culture of bourgeois society after that society had vanished with the generation of 1914, never to return".

Fractured Times: Culture and Society in the 20th Century collects lectures, reviews and previously unpublished essays on a myriad of topics - the fate of avant-gardes, high culture, intellectuals, Jewish history, pop art, the performing arts. There are reflections here on the American cowboy, religion in the 21st century, and art nouveau. He writes admiringly of left-wing figures who popularised science and called for a better, more equal world. Ever comparative, his range is effortlessly global: Tex-Mex, tikka masala; Beethoven, Picasso; the Mona Lisa … and these references all in the same essay. This grab bag is organised around a (very) loosely constructed thesis - namely that "the logic of both capitalist development and bourgeois civilisation were bound to destroy its foundation". This civilisation, outwardly solid and all conquering, believing in progress, devoted to the arts and sciences, was in truth fragile to its core. "It could not resist the combined triple-blow of the 20th-century revolution in science and technology, which transformed old ways of earning a living before destroying them, of the mass consumer society generated by the explosion in the potential of the western economies, and the decisive entry of the masses on the political scene as customers as well as voters."

Hobsbawm's interest in European bourgeois civilisation isn't merely archival; he himself was a product of its last days. Raised in Vienna and Berlin - he emigrated to Britain in the early 1930s - Hobsbawm was intimately familiar with the German-speaking Mitteluropa (the subject of one essay) that produced Sigmund Freud, Robert Musil, Jaroslav Hasek and the scathing Viennese satirist and journalist Karl Kraus, who skewered the pretensions of his age. ("His public life consisted of [a] lifelong monologue addressed to the world," Hobsawm remarks with a deft wit.)

This age has long past; yet, according to Hobsbawm, we still live with its residue. We still rely on shopworn categories created centuries ago to describe situations about art and culture that no longer prevail. This has led to a kind of befuddlement. We are living through "an era of history that has lost its bearings", Hobsbawm writes, "which in the early years of the new millennium looks forward with more troubled perplexity than I recall in a long lifetime, guideless and mapless, to an unrecognisable future."

Fractured Times, as you might expect, is not a very cheerful book. Its pages are full of pained questions about where we have been; there are rather less prognostications on where we might go. But it is also an oddly dispassionate one. Hobsbawm is the kind of person who could tell you the world was ending and barely break a sweat. Yet there is a sly humour at work in a series of lectures he gave at the Salzburg Festival. Here, in one of the temples of traditional high culture, a sceptical Hobsbawm muses on the "dead repertoire" of classical music that his audience has come to enjoy. He subversively twits their vanities. Classical music has benefited from technological reproduction in the form of the CD and other electronic means, but "as long as the repertoire remains frozen in time, not even the huge new audience of indirect listeners to music can rescue the classic music business". (Presumably, the attendees to this lecture did not walk out at this juncture and demand a refund.) Even jazz, once the popular art par excellence, is now a museum piece. (Under the pen name Francis Newton, Hobsbawm wrote about jazz in the 1950s and 1960s.) Sculpture is "scraping a miserable existence at the edge of culture". By contrast, Hobsbawm notes that in the Paris of the Third Republic, the city was gripped with "statuemania", with an average three monuments a year erected.

Hobsbawm also delivers the obituary of another failed 20th-century project - the avant-gardes of modernism. The artists lost their audience to other amusements. What place has the traditional art of sculpture, easel and paint in a world of comic strips, film, radio, and television (and now, the internet)? "It is impossible to deny," Hobsbawm concludes wearily, "that the real revolution in the 20th-century arts was achieved not by the avant-gardes of modernism, but outside the range of the area formally recognised as 'art'. It was achieved by the combined logic of technology and the mass market, that is to say the democratisation of aesthetic consumption. Thus, Picasso's Guernica is incomparably more expressive as art, but, speaking technically, Selznick's Gone with the Wind is a more revolutionary art".

The logic of this statement may strike some as perverse. Hobsbawm's attention to the material conditions of cultural production can lead him astray. Certainly, films had a mass appeal that painting did not. But the criteria for what counts as "revolutionary art" is surely broader than the reach of technology. Hobsbawm's observations often feel shopworn themselves, reminiscent of now stale debates between western intellectuals in the 1950s and 1960s about the pernicious effects of mass culture. It's hard to tell whether Hobsbawm laments the overthrow of the once exclusive preserves of elite culture by the rise of mass consumerism, or rejoices in its downfall.

He picks apart the contradictions of culture under capitalism, but there's a tension between the populist and the man of refinement that the historian never quite resolves. It's a cheap shot to dismiss classic high culture as merely a "niche for the elderly, snobbish, or the prestige-hunting rich". These pages seem haunted by an admission that Hobsbawm never quite makes, and that is the failure of the political project that gave his life so much meaning. He alludes to this in a trenchant essay on the role of intellectuals. The rise of bourgeois culture was underwritten by economic progress - ie the triumph of consumer capitalism - that led not only to its undoing, but the wholesale rout of that "great demonic force of the 19th and 20th centuries ... the belief that political action was the way to improve the world". The triumph of the market has led to "shedding of the old belief in the global progress of reason, science and the possibility of improving the human condition".

This triumvirate of dispositions faces off against other formidable enemies in "the anti-universal powers of 'blood and soil' and the radical-reactionary tendencies developing in all world religions". Hobsbawm is too modest to offer any answers to the problems he outlines; but he also gives us precious little hope that we might find a way out of our own fractured times.

Matthew Price's writing has been published in Bookforum, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe and the Financial Times.