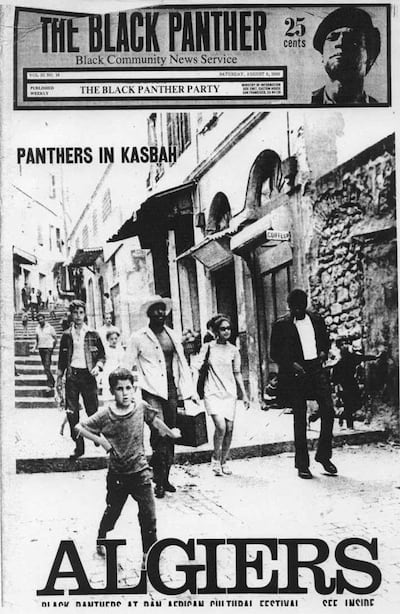

In 1969, Eldridge Cleaver, a leader of the Black Panther Party, fled murder charges in the US and ended up in Algiers – not an unusual place for radical activists to find themselves in the 1960s.

"Once independence was achieved, no one forgot," writes Elaine Mokhtefi in her beautiful new memoir of the period, Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers. "Algeria adopted an open-door policy of aid to the oppressed, an invitation to liberation and opposition movements and personalities from round the world. Everyone was welcomed."

The Algerian capital became home to liberation movements from across the globe as the country, newly victorious, sought to repay the debts of those who supported it in the war. It sent medical specialists to Cuba, China and Lebanon, and welcomed other resistance groups, from those fighting for the Palestinian cause to those involved with opposing the war in Vietnam.

"We overestimated what we were capable of doing," she says. "It was all so new and so extraordinary and so eventful."

'I was the fly on the window'

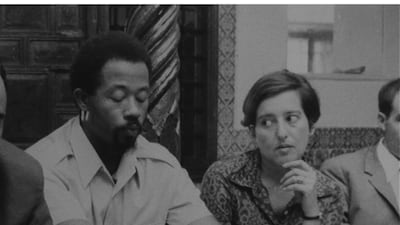

American by birth, Mokhtefi moved to Algiers after becoming involved with the Algerian cause in Paris after the Second World War. She is an unlikely activist: a bookish only child of the Great Depression, she circulated among the different liberation struggles, useful because of her facility with languages, and an independent outsider within Algerian society. "I was the fly on the window," she writes, "looking in, beating its wings."

During the Algerian War, she worked in the New York bureau of the National Liberation Front, lobbying US newspapers to tell the Algerian side of the story. After independence, she moved to Algiers – not an easy place for an American to find employment in the 1960s.

"Everyone thought I was CIA," she says. But her time with the FLN meant the new government trusted her, and she became its chief press officer, writing communiques, translating for ministers, and later, for independence groups.

"I was this one English-speaking woman who was needed by people," she says. "The liberation movements – the ANC [African National Congress], the Zapu [Zimbabwe African People's Union] –they needed my help. They were themselves English-speaking and not French-speaking. I felt that I had a role. I knew I would get a phone call from this one or that one because he wanted to make a statement to the press or wanted to write a letter."

Working with the Black Panthers

When Cleaver arrived, Mokhtefi helped him set up a headquarters-in-exile for the Black Panthers. Their struggle against racial injustice in her own country, the US, resonated with her, and she became a crucial ally. In the end, their overreach and lack of organisational direction meant they lost support in Algiers, and Cleaver was forced to leave in 1972. Mokhtefi, operating around the increasingly repressive government of President Houari Boumediene, was deported two years later, leaving with only her suitcase. An upstairs neighbour told her the police emptied her apartment, and she still does not know what became of her possessions. Her husband, Mokhtar Mokhtefi, joined her in Paris a few weeks later, and they never returned to Algiers.

More than forty years on, Mokhtefi was motivated to write the book simply to document her experiences. “All of a sudden the thought came to me,” she says. “If I didn’t put down my memories, they would be lost. I had no diary, no notes.”

An excellent memoir

The memoir is excellent primary material for those interested in the period. She corrects the historical record several times, as when she disputes the psychologist Claude Lanzmann's account that Frantz Fanon, the postcolonial writer, died before he could say goodbye. Mokhtefi says she found Lanzmann by Fanon's bedside in Washington a few weeks before Fanon died in 1961. But it is also a lovely read, buoyed by Mokhtefi's matter-of-fact voice throughout. "I took some decisions," is all she says about the extraordinary life she led.

A more sensationalist account of her time is possible. She helped smuggle passports between the Black Panthers and the Baader-Meinhof group for a proposed hijacking, and she became an unwitting accomplice to a murder. Cleaver confessed to her that he had killed another member of the Black Panthers, suspecting him of trying to seduce his wife Kathleen.

She was party, too, to Cleaver's other transgressions, navigating between Kathleen and his Algerian mistress and helping to get Cleaver out of Algeria when the country stopped supporting the Panthers.

Throughout, however, she keeps her distance and her cool, giving Algiers, Third World Capital an unlikely, wonderful grounding in solid New England sensibleness. A subtext of the book is the repeated visits of her mother, a woman raised on a farm with only a primary school education, who arrives from time to time, astonished but always supportive.

Mokhtefi's struggle to get published

Mokhtefi spoke earlier this year at the "Axes of Solidarity" conference at the Tate Modern in London, a three-day event co-sponsored by the Africa Institute in Sharjah, that brought together scholars of different international liberation movements.

There is increased interest in this period of Algerian history, but Mokhtefi says she struggled for years to find publishers for the book.

But by a stroke of luck, the journalist Adam Shatz, a contributing editor to the London Review of Books who writes often about Algeria, decided to interview her husband. Mokhtar died before the interview took place, and Shatz took Mokhtefi's manuscript instead. With a touch of pride, Mokhtefi says that "he wrote me the very next day and said he couldn't put it down".

Shatz helped arrange for Mokhtefi to write an article for the London Review of Books, "and as a result, I got two offers, both from British publishers", she says. She chose Verso, who have a history in radical politics and critical theory.

Writing the book led to her return to Algiers for the first time in 33 years: she had been blacklisted, but repeated enquiries at the Algerian consulate in New York paid off in the end.

Today, at 90, she says, "it's not the same city", seeming, as ever, completely unfazed by the change.