Summer is a time of temporary human migration, with many flocking from the Gulf to London for its relatively cool, damp weather and green surroundings. The city has 3,000 parks of varying sizes, the Mayor of London's website tells us, and if you happen to be in one of them, don't forget to look up: you may see a flash of brilliant green, a red-ringed eye, a blood-orange coloured beak.

A few decades ago, Londoners began noticing a new species of bird in their parks: the rowdy, ring-necked, or rose-ringed, parakeet.

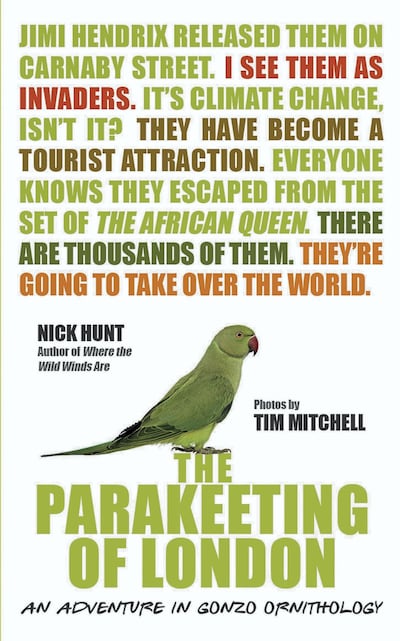

The story of parakeets in London

"One day, you open your eyes to find that ... bright tropical birds live in your local park," writes author and journalist Nick Hunt, who, along with photographer Tim Mitchell embarked on a mission to find out more about the cacophonous creatures – where they come from and, above all, what relationship they have developed with Londoners from all walks of life. The result is an utterly charming new book called The Parakeeting of London: an Adventure in Gonzo Ornithology.

Hunt says the book is deliberately not a work of natural history, and their method was to start out with relatively little information about parakeets, “and instead be guided by other people’s beliefs, instincts, prejudices and outlandish urban legends. It seemed more fun that way.”

The urban legends about how the parakeets arrived in London are indeed extravagant – one such rumour is that during the filming of the 1951 adventure film The African Queen, about half of which was shot in Britain, parakeets were released. But Hunt and Mitchell discover that there were never any parrots or parakeets on the set, and the species in London doesn't come from Africa, anyway – it is Asian. Other rumours include Jimi Hendrix releasing parrots on to Carnaby Street in the 1960s, or thieves breaking into George Michael's estate in the 1990s and accidentally opening the pop star's secret aviary.

In fact, no one really knows how London became the city with the largest parakeet population in what is a Europe-wide trend. In 2012, an estimated 32,000 ring-necked parakeets lived in Britain, although this figure is often attributed to London only, which may be an exaggeration, but is an indication of how their presence is perceived.

The link between avian and human immigration

Hunt and Mitchell randomly interview a park-keeper in Kensington Gardens, female golfers in Hampton Court Palace or a fisherman on the banks of the Thames. But on one of their first forays into Kensington Gardens, they run into an actual ornithologist, sporting khaki waterproofs with binoculars around his neck. He tells them about "flyways", or organised paths in the sky that parakeets use like commuters; "an alternative transport network existing just above our heads, which we had not seen before; as if a new green line had appeared on the Underground map."

Against a politically charged and Brexit-infused background, what quickly becomes apparent in Hunt and Mitchell’s conversations with Londoners is that these small birds, primarily from southern India, become synonymous with how people feel about immigrants. The women golfers in Hampton Court Palace comment on the parakeets’ squawking, which is “not a noise that is English. Not normal English birdsong. Perhaps our hawks and our kites will eat them …”

A groundsman interviewed in Kensal Green says: “It’s like the Mongols, innit? Coming over here from Asia or whatever. Invaders. Killing things. Like a crusade …”

Some people they encounter affirm that parakeets terrorise other species while others observe that they are humble and seem to coexist with other birds. And one woman poses the question: “The parakeets … I think it’s rather exotic. But when do you stop being – ooh! – a refugee? When do you become a Brit?”

When I asked Hunt about the parallel between the parakeets and immigration, he said that conversations with people often led to this subject. “In a city as diverse as London, though, responses were, by and large, more positive than negative … many people still think of American grey squirrels as invasive newcomers – but Brexit has obviously had the effect of bringing everything into sharper focus, and often putting a nastier slant on people’s words.

“The link between avian and human immigration was always lurking under the surface somewhere. The book doesn’t mean to imply that everyone who is concerned about invasive species is a racist, because obviously the situation is much more fluid and complex than that. We only met a couple of out-and-out xenophobes on these walks.”

Is there a reason to worry about the birds?

If you Google "parakeets", a certain number of university studies appear that sound very dramatic, such as the following one, from the University of Brighton: "Invasive alien parakeets pose a number of risks to Europe's economy and society, which worryingly are likely to increase as global climate change creates a warmer Europe." Some scientists are even asking if the parakeets should be culled – which entails selective slaughtering.

Hunt doesn’t see much reason to worry. “In terms of the risks facing Europe’s economy and society, parakeets have got to be pretty low on the list! Sounds like hysterical scaremongering. Almost every one of the ecologists and ornithologists we’ve spoken to has been pretty relaxed about the spread of parakeets. It’s really too early to tell what effect they are having on native birds … The threats facing native British birds don’t come from invasive parakeets, but from native British people. Given the war humans wage on nature, scapegoating a few small green birds is ridiculous.”

In the meantime, Hunt asks in The Parakeeting of London, whether a case could be made for parakeets as the ideal Londoner? "While garrulous, brash and confident, they keep themselves to themselves, getting on with their routine and minding their business."

Moreover, these colourful, vibrant and now naturalised parakeets give Londoners a sense of hope, writes Hunt: “Against a backdrop of grinding, relentless environmental gloom – when the dominant narrative of our times is one of collapse and disappearance, of habitats being destroyed and animal populations thinning out … parakeets are flourishing, an expanding wild population in the middle of our most developed, most overcrowded city.”

The next time you’re in a London park, it may just seem a little more tropical …