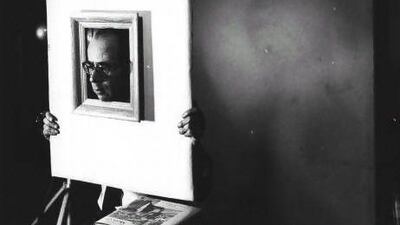

The photographer Philippe Halsman produced some of the 20th century’s most recognisable portraits – from his picture of the model Constance Ford against the US flag used in Elizabeth Arden’s Victory Red lipstick advertising campaign, to the celebrated “jump” photographs (from which Austin Ratner’s novel takes its title) that pictured screen sirens such as Audrey Hepburn and Marilyn Monroe off their guard, their skirts billowing around them, giggling like schoolgirls in mid-air.

These tragic events set in progress what Ratner describes as “an early chapter of the Holocaust that is now mostly forgotten in the English-speaking world”. Despite nothing but circumstantial evidence that the son had committed the crime, he was imprisoned in Innsbruck and tried twice (the pronouncement of the first trial was challenged) for patricide in a court and a country that was vehemently anti-Semitic.

Inspired by André Gide's statement that "fiction is history which might have taken place, and history is fiction which has taken place", Ratner explains that The Jump Artist is "based on a true story", combining the "known facts about Halsman's history" with "what might plausibly have been the case".

This makes for an intriguing mix of fact and fiction – an increasingly admired device given the rise in popularity in recent years of biographical novels such as Hilary Mantel's Man Booker prize-winning Wolf Hall and its recent sequel Bring Up the Bodies, or The Paris Wife, Paula McLain's fictionalised account of Ernest Hemingway's first wife, Hadley, that appeared last year.

The horror of Halsman’s treatment at the hands of his captors is juxtaposed against a description of a trial that is so clearly prejudiced and unjust that it reads as near farcical in parts. The prosecution’s case is based on nothing but pure racial hatred – the mere fact that Halsman is Jewish is enough to ensure the alpine-dwelling locals take matters into their own hands, branding and interning him as a murderer from the get-go.

The story itself is indeed fascinating but the execution is sometimes a little hazy by comparison. The internal monologue and switch between past and present, flashback and dream is somewhat confusing, especially at first, meaning it’s not an easy novel to sink one’s teeth into.

This is perhaps most beautifully rendered in the symbolic image he imagines Halsman capturing of his father’s fall: “It was pictorial and still, like an image on a photographic plate – his father tilting backwards off the trail at an incredible angle, hands clutching the straps of his rucksack.” Given that Halsman advocated “jump” photography because he believed it stripped his subject of their reserve, revealing their soul, this image provides a hauntingly tragic counterpart to the photographer’s most famous works.

Lucy Scholes is a freelance journalist who lives in London.