In the rooftop garden of publishers Gingko, a stroll from the Thames in London, are two small gingko (or maidenhair) trees. I'm here to meet Barbara Schwepcke and Bill Swainson, editors of A New Divan, a collection of poems and essays that comprises work from more than 50 poets and scholars from the Middle East, Europe and elsewhere.

Schwepcke, chief executive of the publishing house she founded in 2014, plays with a leaf while explaining the book's origins. "The leaves appear to be two, and yet are one," she says. "On September 15, 1815, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe sent a dried gingko leaf to his beloved, Marianne von Willemer, as well as a poem, both to say goodbye and to symbolise his deep love."

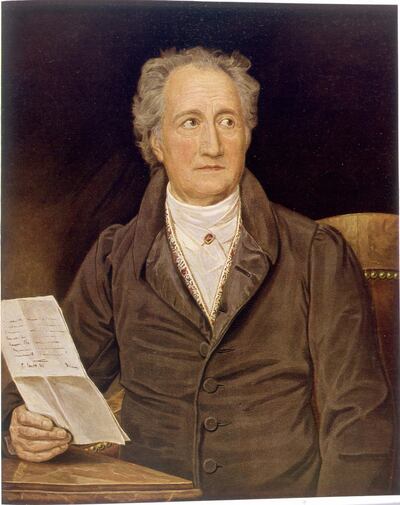

Germany's national poet

Long before her publishing career focused on the interchange between the West and the Middle East, Schwepcke knew the work of Goethe, Germany's national poet. "Growing up, I was aware you always quote his work in any speech before the family," she says.

Goethe was interested in the Middle East and the Quran, but in 1814 he read a German translation of the works (divan) of 14th-century Persian poet Shemseddin Muhammad, better known as Hafiz. Five years later, Goethe published West-ostlicher Divan (West-Eastern Divan), 12 "books" of poems and explanatory notes that became what poet Eric Ormsby describes as "a decisive reconfiguration of German, and indeed European, poetry". Schwepcke says that with the Divan, "Goethe was trying to build a bridge between two cultures, pointing out what we have in common, through both poetry and scholarship".

The West-Eastern Divan has many layers. Goethe is conversing with his "twin", Hafiz, but also with Willemer, who at the age of 30 was 35 years younger than Goethe. They met shortly after he read the work of the Persian poet. "She was young, vibrant, artistic, a musician, a dancer," says Schwepcke. "She entered a real lyrical dialogue with Goethe – they exchanged letters, some in cipher, using Hafiz's poetry as the code."

'A passion for translation'

Goethe believed an East-West dialogue would continue long after him, and this was the challenge taken up by Schwepcke when she announced a new divan on September 15, 2015, the 200th anniversary of Goethe's letter to Willemer. Schwepcke recruited Swainson, a renowned editor in literary translation who has worked with writers such as Amin Maalouf, Juan Gabriel, Delphine de Vigan and Matthew Sweeney. "We shared a passion for translation," she explains. "I was the prose person, Bill had expertise in poetry, with the knowledge and connections this venture needed."

They believed translated poems should both reflect the original work and stand on their own merit. A New Divan has the Arabic, Farsi, Turkish or Slovenian poem printed across the page from its English version. Poets were assigned themes that had been used by Goethe as titles for the 12 books in West-Eastern Divan, including The Poet, Love, Faith, Paradise, Proverbs and The Tyrant. "The challenge was to commission new poems from the best poets we could persuade to take part," says Swainson. "They had either to be familiar with Goethe or to respond to his ideas. We wanted them to speak to the world we are in now."

Swainson drew on his myriad contacts, such as Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti. Swainson remembered that Barghouti lived in Hungary after he was deported from Cairo in 1977, before returning to Amman and Beirut. "Barghouti has a cool, poetic voice," he says.

To translate Barghouti's work into English, Swainson thought of George Szirtes, who was born in Budapest but fled to England when the Soviet Union crushed the 1956 Hungarian uprising. "I wanted an Eastern European clarity," Swainson explains.

There is a piercing lucidity to The Obedience of Water, written by Szirtes after Syrian Khaled Al Jbaili's literal translation of Barghouti's poem, which addressed The Tyrant theme. If there are echoes of Hafiz meeting Timurlane, or Goethe meeting Napoleon, Barghouti's poetic tyrant has a startling, up-to-date feel.

Strong female voices

"We also wanted female voices in A New Divan," says Schwepcke. Swainson approached Nujoom Alghanem, a poet and film director from Dubai who has published eight collections of Arabic poetry, the most recent of which is translated into English as I Fall Into Myself. Alghanem chose the theme of "Suleika", the Biblical and Quranic figure who fell in love with her husband's slave, Joseph. In Hafiz, Goethe found an unusually positive portrayal of Suleika, and in the West-Eastern Divan, Suleika also reflects Willemer.

Alghanem admits she was wary of poor translations of both Goethe and Hafiz. "When you grow up with the titans of classical Arabic poetry, whether the pre-Islamic period or after, you develop a sophisticated taste for poetry," she says. "I was eager to know more about the cultural resources that had influenced Hafiz and Goethe. It was quite fascinating to learn how the mystical and agnostic traces that are found in Hafiz's poetry made his work so profound and influential throughout history."

Historians have long traced the rhythms of Arabic poetry in Persian poets. As American scholar Richard Frye once wrote: "It was really Arabic which gave New Persian the richness which engendered the flowering of literature, primarily poetry, in the late Middle Ages."

Irish poet Doireann Ni Ghriofa worked on the English version of Alghanem's The Crimson Shades and the pair discussed its vocabulary in depth. "She captured the indirect rhythm in the poem and highlighted it," says Alghanem. "I was relieved that the integrity of the poem was kept intact."

Meanwhile, Lebanese poet Abbas Beydoun took the theme of "Hafiz". For his work, he looked to Quranic and Biblical stories, a refugee camp and Marilyn Monroe, while reflecting on 74 years in which he has experienced war, love and jail. "I don't know Hafiz well," says Beydoun. "I thought instead about Goethe and Jallal Eddine Rumi, who wrote an outstanding poem about Suleika, which I had read translated into Arabic.

"My poem compares two women who are symbols of love, one historic and one modern. Suleika summoned women who had reproached her for falling in love with Joseph, and gave them all lemons and knives with which to chop them.

"She then called Joseph. When he arrived, they were so distracted by Joseph's appearance that they cut themselves, thereby staining their fingers with the love of Joseph. Beauty takes away from the lover the consciousness of self."

The inspiration for 'A New Divan'

A New Divan opens with Letter to Goethe by Adonis, perhaps the leading modern Arab poet, translated by Libya's Khaled Mattawa, who also contributes a poem. For Mattawa, who had already translated Adonis for 2010's Selected Poems, the Syrian wordsmith is "almost a high modernist" akin to Wallace Stevens or John Ashbery. "His selection of language is precise. Sometimes he chooses older words, uncommon words," Mattawa says. "Most people associate Adonis with a certain detachment. His imagery is surreal and dense."

Mattawa sees his own poem as a response to Goethe, whose naturalism influenced his 2003 collection, Zodiac of Echoes. "Perhaps the inspiration for A New Divan is a time when Goethe went to the East with admiration," Mattawa says. "He felt there was much to appreciate in Arabic and Islamic civilisation. Cultural differences are a blessing rather than a curse."

For his own poem, Mattawa looked south. "I thought about the travelling poet, and evoked an eye-opening trip I made to Madagascar," he says. "I wanted the poet to see the global south. Poets from the East and from the West should look at the dangers that surround them, whether inordinate inequality or the ecological threats to the earth."

Among other poets featured in A New Divan are Iraq's Fadhil Al Azzawi, Amjad Nasser from Jordan, Raoul Schrott from Austria and Antonella Anedda from Italy. Gingko will this year also publish a new English translation of West-Eastern Divan by American writer Ormsby, who is fluent in German, Farsi and Arabic.

Back on the rooftop garden at Gingko, Schwepcke and Swainson take delivery of the first copies of A New Divan sent from the printers. Schwepcke signs one for me as "the mad one". Swainson signs as "the lucky one". They're clearly bemused, as well as delighted, by what they've unleashed. They should be.

____________________ Extracts from 'A New Divan'

Nujoom Alghanem, ‘The Crimson Shades’

Literal translation from Arabic by Suneela Mubayi

English version by Doireann Ni Ghriofa (extracts)

When you still didn’t arrive, I turned to the winds and cried,

Oh, and as I waited, I fell in love with love.

I willed snow’s cheek-scorch to heal my heart.

Now I make my home in the full moon, infected as it is

by my desire-pangs

and my dreams rest in desert clefts.

…

Might we bribe the fire-jinns to hide us in a poem like

metre or rhythm? Might our myth,

if written in the book, be to their satisfaction? Might

we allow ourselves contentment

to sip kisses on kisses? Which wind might we bribe?

Which breeze will conceal us:

the easterly, or the westerly?

Mourid Barghouti, ‘The Obedience of Water’

Literal translation by Khaled Al jJbaili

English version by George Szirtes

When he takes his seat he doesn’t descend from

heaven

on a cloud, no, he climbs up on our shoulders, yours

and mine

and sits in the saddle of time dangling his legs,

two legs not six, if you care to check.

His mirror loves him. He loves his mirror. The love is

mutual.

Abbas Beydoun, ‘Suleika and Marilyn’

Literal translation from Arabic by Reem Ghanayem

English version by Bill Manhire (extract)

I am searching for blood for my poem.

My fingers grow sharp as I write it.

I find Suleika in a refugee camp.

The hot iron she carries

burns and blisters her fingers.

On the wall, a photo of her dead brother;

I can see how her hands bleed as she does the dishes,

how her beauty is there in the rags she wears.

And now I am thinking of Marilyn Monroe.

She took her life because the world is made of pain

plus tiny scraps of love. She shone high on the screen

and a million men returned to their lives. Ah, they said,

is she quite stable? One day she will surely grow up

and acknowledge our worth!

Adonis, ‘Letter to Goethe’

Translated from Arabic by Khaled Mattawa (extracts)

Is it time, dear spring of my freedom?

I’ll go on walking.

Is the East veering away from the West, offering its

heavens

to another moon?

I’ll go on walking …

The West is behind you, but the East is not before me.

They are two banks of one river.

One has become more than an abyss,

more than a rock;

Sisyphus is its voice screaming ….

Khaled Mattawa, ‘Easter Sunday, Rajab

in Mid-Moon’ (extract)

What does love mean

in a time of love unspirited? he asks, the body a rope of flesh and words pulse of the sun’s touch - how vision was merely skin once he recalls how once upon a time

we caught the scent of poppies with our hands …