Syria has been left broken and divided by the civil war that has raged since 2011, when security forces cracked down on peaceful protesters. President Bashar Al Assad's regime has survived, but at a bloody cost.

About 500,000 have been killed in the fighting that continues sporadically to this day, millions of Syrians have fled abroad, cities have been destroyed and sectarian divisions have become entrenched. While the ruined nation may appear beyond repair, a new book by a leading historian of the Arab world offers a model of hope from Syria's own history for how the long process of reconstruction and reconciliation might begin.

Professor Eugene Rogan’s The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Destruction of the Old Ottoman World explores the causes and consequences of the massacre of thousands of Christians by their Muslim neighbours in Damascus in the mid-19th century.

Drawing on an array of historical sources and a cast of colourful characters from the period, Rogan recounts how the people of Damascus descended from living in relative harmony into a “genocidal moment”.

While the ominously named Hawadith ash-Sham, or the Damascus Events, may reveal the darker side of human nature, Rogan suggests Ottoman authorities were largely successful in pulling the city back from the brink and fostering long-term reconciliation.

“I hope that for Syrians to see that in the mid-19th century, there were local solutions to local problems, that there is a pathway back from the brink of mass murder towards reconstruction, and, with reconstruction, through providing the prospect of a better future for the next generation, you can achieve reconciliation,” he tells The National.

Rogan locates the long-term context of the massacres in the history of Damascus, a city he visited often from a childhood home in Beirut, and whose archives he consulted in his research.

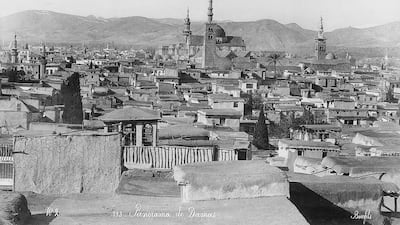

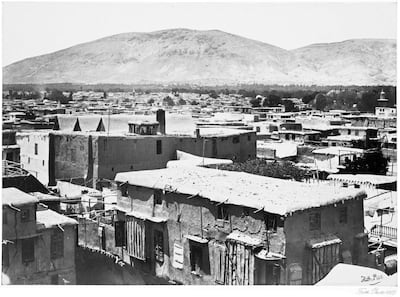

In the early 19th century, Damascus was one of the major provincial capitals of the Ottoman Empire. Damascenes were known for taking pride in their city, which was nicknamed Damascus the Fragrant, and considered one of the hearts of the Islamic world.

Hub city

While Damascus was an important Islamic centre, in part due to its historic role as a departure point for the annual Hajj pilgrimage to Makkah, the city was home to a diverse population. By the mid-19th century, about 85 per cent of the city's inhabitants were Muslims, including Arabs, Turks, Kurds and Persians. About 10 to 12 per cent were Christians from various sects, with a small Jewish population of less than 5 per cent.

Under Ottoman law, Christians and Jews were granted security and property, but were legally second-class citizens. Despite the rigid religious and social hierarchy, intercommunal outbursts of violence were rare. This order began to unravel through the first half of the 19th century as social and economic change swept Syria, stoking tensions between the Muslim majority population and minorities.

Beginning in the 1830s, European influence on the Ottoman Empire increased, and the region began to undergo rapid societal upheaval. Damascus had already been losing economic importance as the Ottoman Empire entered European markets, with trade shifting to the coastal city of Beirut.

While many Muslims fell on hard times, Christians began to benefit from the influx of European goods and trade. Employment as economic agents and consular staff granted them economic privileges over their Muslim competitors.

In 1856, under pressure from European powers, the Ottoman government granted Christians and Jews legal equality for the first time. These changes laid the ground for growing resentment among Muslims, who saw Christians as upending the social order and arrogantly flaunting their newfound privileges.

"Violence was brewing. There was a growing perception that the Christians of Damascus were in some ways displacing the role of the Muslim elite as the dominant group in the city," Rogan says.

In early 1860, the Druze massacres of Maronite Christian civilians in neighbouring Lebanon provided a "precedent" for Muslims in Damascus. Having identified the local Christian community as an existential threat to their standing, wealth and position, “they began to conceive of extermination as a reasonable solution".

During eight days of unprecedented lawlessness, a mostly Muslim crowd attempted to exterminate the Christian population. An estimated 5,000 were killed. Hundreds more were forcibly converted, with children abducted to be brought up as Muslims, and women were raped. The churches of Damascus were destroyed and the homes of most Christians were burned down.

Eighty-five per cent of the population, however, was saved, primarily by the Algerian anti-colonial leader Abd al-Qadir and his men stationed in the city, along with some of the Muslim elite, who provided shelter.

In the aftermath of the massacres, the city was left deeply divided with Christians fearing further attacks, and Muslims fearing revenge. The Ottoman authorities needed not only to restore law and order but also to heal these tensions and restore peace and prosperity. The situation was further complicated by pressure from European powers, whose demands for revenge for their Christian proteges were backed by the potential threat of a military occupation of Syria.

Rogan argues that the Ottomans dealt with these challenges slowly but admirably and ultimately effectively. He charts how thousands of Muslims who were implicated in the riots were arrested shortly after the arrival in the city of the newly appointed Ottoman governor, Fuad Pasha. More than 150 were executed, including the former governor, who had failed to stop the massacres.

While control was regained, many Muslims resented the draconian punishments and Damascus remained divided.

Tax to rebuild

The badly damaged city needed restoration, while most of the Christian population had lost everything they owned and needed compensation. Partly to placate European demands, the Ottomans imposed a tax on Muslims to pay for the losses. Although the money raised was insufficient, it allowed Christians to begin to rebuild their homes.

The true process of reconciliation came with the onset of economic opportunities and shared prosperity from the mid-1860s onwards. Central to the Ottoman plan was the creation of a new province, or vilayet, of Syria in 1865, combining the provinces of Damascus, Jerusalem and Sidon. Damascus was made the capital of the new province, and the combined tax revenues were funnelled into the city.

"It created five times the revenues flowing through Damascus, allowing massive infrastructural investment, creating markets and jobs, communications, infrastructure, education opportunities," explains Rogan.

Crucially, the newfound prosperity was shared between different communities. An elected general council comprised of Muslims and Christians from across Syria was tasked with ensuring spending was shared equitably.

"Suddenly, the gains of one side are not at the expense of the other," he says. In this process, Rogan sees potential inspiration for today’s Syria.

While Syrians still criticised elements of Ottoman rule, including corruption, shared prosperity allowed the city’s divided groups to live and work together again. Unlike in neighbouring Lebanon, where 1860 is seen as the origin of a sectarian system that still endures today, Rogan says that Syria did not inherit a sectarian legacy.

Instead, most Syrians embraced a shared secular national identity, from Ottoman rule through the French mandate period and into independence. While there have been outbreaks of communal violence in Syria, it was not until 2011 that the country descended into mass sectarian division and bloodshed.

Rogan points out that both the context and the magnitude of today’s crisis make it in some ways “incomparable” to 1860. Whereas the Ottoman authorities were able to restore order and pump funds into Damascus, today the Syrian government controls only 70 per cent of the country and depends on its Russian and Iranian backers.

About 90 per cent of Syrians are currently living below the poverty line and reconstruction estimates range from $250 billion up to $1 trillion.

Next generation

Even then, Syria is only one of many “broken countries” in the region requiring reconstruction, including Iraq, Libya, Yemen and most recently Gaza, spreading international funding and attention thin. The regime has also lost the trust of many of its people and has alienated much of the diaspora living in exile.

For these reasons, Rogan says it is hard to conceive of reconstruction happening under the Assad regime. Yet he believes that history still provides an encouraging message for the region today in spite of the fragmentation of the past 13 years.

"It is the prospect of a better future for the next generation that will enable the current generation to lay down the hatchet and turn the page to move forward," he says. “There is hope that Syria will one day, once again, restore its sense of community and civility, to be a whole country."

The Damascus Events: The 1860 Massacre and the Destruction of the Old Ottoman World by Eugene Rogan is available in hardback now.