May Muzaffar’s remarkable memoir Story of Water and Fire begins as a love story between a young Iraqi woman and her artist suitor. He vacillates; her mother equivocates; Muzaffar bides her time. Ultimately, they find themselves in an “ideal marriage” – a meeting of minds where she writes and he paints.

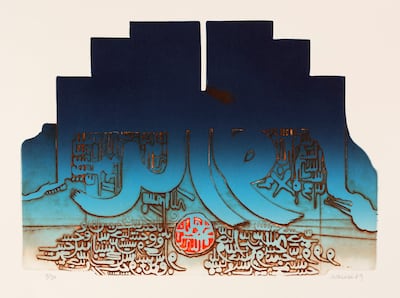

Muzaffar and her husband, the painter and printmaker Rafa Nasiri, were key figures in the 1970s generation of Iraqi art. The couple travelled together frequently, with Nasiri showing internationally at places such as the Asilah Arts Festival in Morocco, while Muzaffar wrote poetry, short stories and criticism that chronicled this exciting time in the chapter of Arab art.

Published last year, Story of Water and Fire is part tale of this cultural milieu, and part a requiem for a country destroyed by conflict. Muzaffar and Nasiri remained in Baghdad throughout the Iran-Iraq War and the Gulf War, but left afterwards for Jordan and watched the 2003 invasion from afar. Muzaffar still lives in Amman, where she still runs the Studio Nasiri even though her husband died 11 years ago.

When they first met in early 1971, Muzaffar worked at an insurance company in the Iraqi capital. Nasiri and Dia Azzawi (another pioneer of Iraqi art and sculpture) had been commissioned to paint murals in the building. Her office was on the ninth floor, and Nasiri would climb the stairs – as the lift was not yet installed – to hand-deliver openings to exhibitions and activities at the arts centre, or find other pretexts to come to talk to her.

“I loved his work before I fell in love with him,” Muzaffar tells The National. “At the time, freedom in society was limited. My family was well-known. He was known also as an artist, as was his family. We had to do everything in secret. We used to speak on the phone all the time.”

When they married, Nasiri transformed his studio attached to his family house into an apartment for the two of them. They had fruit trees in the garden and hosted Iraqi poets and artists, such as Azzawi and Saleh Al-Jumaie.

The artists of this period, some of whom are referred to as the New Vision group, wanted to give a “fresh look”, Muzaffar says, to Iraqi identity, inspired by the country's heritage. Spurred on by the Six-Day War, which took place between Arab states and Israel in 1967, they also looked to pan-Arabism, playing with the form of the Arabic letter.

“May was just starting in the 1970s but quickly became an important critic because of her sensitivities to the art scene,” Iraqi-British art historian Nada Shabout tells The National. “She had a good eye for detail. Because of her relationship with Rafa, she witnessed first-hand what was developing, and delivered analysis and context around it.”

These artistic ambitions were well supported by the Iraqi state, which had long offered bursaries for writers and artists and acquired work for its public museums. In 1972, Baghdad hosted the Al-Wasiti Fine Arts Festival and, two years later, the Baghdad Biennial for Arab Art, which convened artists from across the region and cemented the city's prominent cultural role.

“We owe much of our knowledge of the history of the period to her writings,” says Shabout.

The wartime years

Muzaffar's memoir makes a substantial contribution to literature around the Iraq war with its bravura account of life under the 1991 US bombardment.

It begins when Muzaffar and Nasiri were living in a house in the suburbs, which they had designed in modern style with an architect. As Muzaffar vividly describes, they spent the first night of the war in a corner beside their kitchen.

The next day, they passed on their neighbour’s invitation to join him and his family in the bomb shelter he had erected in his new house. Instead, they drove through the quiet afternoon – the air strikes took place at night – to Muzaffar's brother’s house, so that the family could be together.

“We were nine people living in a house with no electricity and no water other than what was in the tank,” Muzaffar recalls. A few weeks later, the affluent neighbourhood next to them was struck, and the whole family decided to decamp to Muzzafar and Nasiri's home in the suburbs. They rode out of the rest of the war in the modernist house, rationing food, water and paraffin.

The sequences about the 1991 invasion are particularly important because few Iraqi accounts of the period have been published in English (though more have recently emerged in the past five years). Muzaffar deftly frames not only the US bombardment but also the rapid decline of the country afterwards, the emotional tensions of life in the diaspora, and the complicated process of realising they would never return.

Like many, Muzaffar and Nasiri wanted to stay in Iraq after the war, but the security situation was too difficult. They left for Amman, which functioned as a refuge for Iraq's displaced art scene. They left their house, which contained Nasiri’s paintings and their substantial library, and paid a caretaker to look after it.

A few years after the 2003 invasion, they received a call from a neighbour: the house had been trashed and a strange car was parked in the driveway. They learnt that their caretaker had been killed some time ago at a military checkpoint. The new inhabitant had cleared out the rooms, which were by then infested with insects and animals, but carefully looked after the artworks and books.

They let him stay, but set about moving artworks to Amman. Princess Wijdan Ali, then head of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, offered to host a retrospective of Nasiri’s work – which gave the works the pretexts for exit papers – and at last Nasiri's art left Baghdad. They gave their impressive library to a friend.

Nasiri died in 2013 in Amman, and Muzaffar began writing the book soon after – initially, as a process of mourning, she says. She wrote it over the course of seven years, and it was first published in Arabic in Beirut. The English edition, translated by Jennifer Leigh Peterson, now appears as part of an initiative set up by Al Mawrid Arab Centre for the Study of Art at NYU Abu Dhabi.

“Muzaffar's book is the first in a series of translations of memoirs or primary documents written and published in Arabic,” says Salwa Mikdadi, who founded Al Mawrid. “Prior to the 1990s, the majority of books on Arab art were written and published in Arabic. Through these translations, Al Mawrid offers wider access to key primary texts on the development of visual art in the Arab world.”

The centre is now working on three more volumes.

For Muzaffar, the book was not only a chance to revisit her life with Nasiri but also to educate a new generation, particularly with the English translation.

She included a number of details, such as an air strike in which 400 civilians taking sanctuary in a nuclear shelter were killed, because she realises how little people outside Iraq still know about the war.

“Many Americans, they don't even know about” the Amiriyah strike or what the war was like, she says. “So that's why I put everything in there – and in a simple way.”