"I will write books and compose poetry for as long as I live," writes Nur Begum, who embarked on a three-month pilgrimage to Makkah with her mother and husband in 1931.

"No matter how much they gossip and reproach me, I will never regret it. I have no offspring in this world, but I do have this divine calling; people are remembered by their children, but my legacy shall be this!"

Hers is only one of many female voices included in the book, Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women, released on Tuesday. It is a collection of lesser-known writings of Muslim women, who travelled far from their homelands for pilgrimage, education, politics or pleasure.

Until now, historic travelogues have been dominated by men, such as the legendary 14th-century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta, whose writings made him famous the world over. Similarly, the few women whose names have been immortalised tend to be those with European heritage — Margery Kempe, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Mary Kingsley.

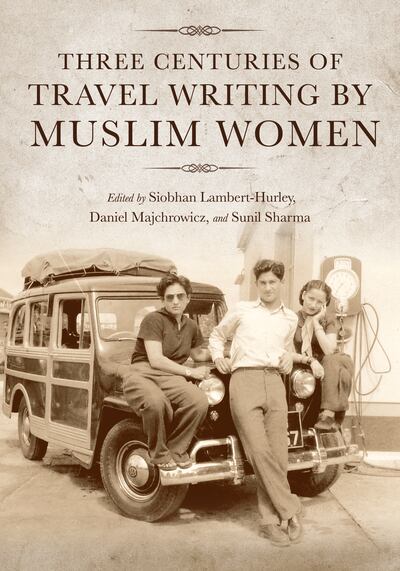

Compiled by editors Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, Daniel Majchrowicz and Sunil Sharma, Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women showcases writings from 45 Muslim women — acquired through an extensive selection of writings in 10 languages, including Arabic, Turkish, Urdu, Punjabi, Indonesian, English and others.

The editors initially received funding from the Leverhulme Trust for a project on Muslim women travellers from Asia and the Middle East, which paved the way for the extensive research that went into finding the writings in the collection.

Lambert-Hurley says the idea for the book emerged from an earlier project she completed with Sharma on Atiya Fyzee’s 1906 travel diary. “We realised that there were many more travelogues by women and envisaged a large translation project," she says.

Before joining the team, Majchrowicz had already compiled several travel accounts by Muslim women, as part of his research into the history of travel writing in South Asia.

With writings spanning the 17th to 20th centuries, the team spent seven years producing the anthology, piecing together work by royal family members, women from influential families, and even a few from modest backgrounds.

The very first traveller we are introduced to in the collection is a woman known only as the “Lady of Esfahan”. Originally writing in verse form in Farsi, she details a pilgrimage to Makkah after the death of her husband.

She writes: “Since wily fate made me suffer separation from my dear beloved, repose in bed was forbidden to me. I saw no recourse other than travel. I could neither sleep at night nor rest during the day until I would be able to circumambulate the sanctuary of the Kaaba. I prepared myself and set off with a resolve in my step.”

Some excerpts included in the anthology were part of private collections and had never been published, while others, such as the Lady of Esfahan’s, were buried inside collections in their original languages.

Others were discovered through earlier work on lost manuscripts and published in journals, such as an excerpt by the Mughal Princess Jahanara Begum. The princess’s contribution, documenting an initiation into a Sufi order in Lahore, is the second of the two pieces from the 17th century.

Several writings were sourced by the editors from autobiographical accounts, essays, lectures, poems, magazine articles, letters to family and private diary entries. Some letters and diary entries, such as those by Begum Sarguland Jang, Ummat Al Ghani, Nur al Nisa and Muhammadi Begum, were meant only for circulation among family members.

Lambert-Hurly says finding sources involved quite a bit of detective work. Sharma adds: “Some of the works were published for private circulation and we were able to find the rare copy from various individuals.”

For many of the women, travel enabled them to reflect on people and places that differed from their own. Their writings offered an intimate glimpse into the inner lives of women who were otherwise not seen or written about. Through their work, they could compare the landscapes of their own worlds with those of others.

However, several excerpts in the anthology go against the trope of women’s writing being centred on private spaces.

Dilshad — a poet, historian and teacher from Tajikistan, who was captured and forced to migrate to Uzbekistan when her hometown was invaded — weaves her personal history around the political and cultural upheavals surrounding her.

In another excerpt from Egyptian journalist Amina Said’s travelogue on India, we read about her observations about Indian cities, and how she set about correcting misinformed perceptions she encountered in the country regarding the Palestinian crisis.

Muhammadi Begum, meanwhile, writes about colonialism, while Zeyneb Hanoum ponders whether the women of "the Orient" require saving.

Several of the writings detail women's experiences of the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Makkah. Nawab Sikandar Begum describes pilgrims having to undergo quarantine on Kamran island, off the coast of Yemen, a reminder that travel restrictions date back far longer than the Covid-19 crisis.

Meanwhile, as Rahil Begum Shervaniya takes issue with the lack of privacy in the communal women’s showers, Nur Begum’s rhyming verses portray it as a space where women are drawn together in their shared quest to cleanse themselves before Hajj.

Over the centuries, the writings depict how the arduous road travel by the Lady of Esfahan evolved into a journey by sea, preceding the far easier journey by plane completed by Lady Evelyn Cobbold, who claimed to be the first European woman to complete Hajj.

Each of the chapters opens with biographical details of the women, and contains an analysis and context of their writing. Many additional excerpts, not appearing in the book, have been compiled on the website Accessing Muslim Lives.

Majchrowicz says: “Some of the additional translation that did not fit in the book can now be found on the website. We also felt it was important to give access to the original texts, in their original languages, to the greatest extent possible.

“Readers who are able to read the original languages can go to the website and hear their words directly, without a translator’s mediation. Finally, the website offers a space for us to include the works of new authors as we find them.”

Reading through the book, readers are immersed in the cyclical nature of global disturbances, be it in the form of disease, war, forced immigration, or the fight for the right to live peacefully.

What emerges is a group of women writers who were not afraid to voice their thoughts in the presence of authority figures and unfavourable circumstances. Three Centuries of Travel Writing by Muslim Women Writers is an enduring testament to just a few of the countless fascinating stories documented by women travellers throughout the ages.