When Jaspreet Kaur describes using her mother’s Jolen Creme Bleach on her sideburns when she was 11 because a boy at school said that she looked like a gorilla, repressed memories from many readers' early teenage years of that teal-coloured tub of cream will come to mind. Jolen Bleach is a staple in the bathroom cabinets of many young South Asian women, something Kaur addresses in her book Brown Girl Like Me: The Essential Guidebook and Manifesto for South Asian Girls and Women.

After recalling a string of makeshift hair removal fiascos, Kaur explains that brown girl body hair follicles are thicker than lighter-skinned hair by genetic design. “They won’t go down without a fight,” she writes, before pointing out contradictions in the public portrayal and acceptance of body hair: when white women flaunt armpit hair it’s seen as feminist and revolutionary – but on brown women, it’s “grotesque".

author

Body hair is only one subject explored in this wide-ranging manifesto, which contains the voices of psychologists, artists, comedians, educators, well-being practitioners and more. Chapters tackle topics such as education, menstruation and shame, cultural appropriation, dating and relationships, parenthood, social media and mental health, and each begins with a poem penned by Kaur.

Kaur began writing in March 2020, but says the book was seven years in the making. “I had the concept for quite a while, and the ideas for the chapters formed over the years,” says Kaur, who has a background in gender studies and taught history, sociology and politics in London secondary schools.

Brown Girl Like Me, published by Pan Macmillan’s award-winning non-fiction imprint, Bluebird, releases on February 17.

Lifting the lid on mental health

The book opens by exploring mental health – a chapter Kaur believes is the most urgent and pressing, as she questions why we in brown communities equate strength with silence, and urges that we take action to destigmatise mental health issues. She looks at how depression is often seen as a “white” or “western” problem, and how western therapists, with their white lenses, often misunderstand South Asian cultures and families, urging patients to adopt more “independent” lifestyles. But “the outright dismissal of our traditions is not the solution”, writes Kaur, who lists faith, family and culture as “other variables” that brown girls often have to consider.

Kaur cites black and Indian feminist writers such as bell hooks and Arundhati Roy as inspirations, as their writing styles interweave their personal experiences with research and activism. For while Brown Girl Like Me is packed with facts and stats, it isn’t purely academic – it’s laced with anecdotes from Kaur’s own life. “I wanted to be honest and open because I knew that including and interweaving my experiences alongside the academic research and the interviews with other women, was what would open up people a little bit,” Kaur tells The National.

Inclusive of all brown women

At the same time, Kaur acknowledges that brown girls are an incredibly diverse faction. “I recognise that the brown woman’s experience isn’t just one single experience,” says Kaur. “There are so many differences and there isn’t only one story or one voice, but I wanted to show how many similarities we all have because we all exist in brown bodies.” She also ensured that her research sample contained demographics from different regions – from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, for instance, as well as a variety of ages.

“The youngest interviewee from the book is around the age of 16, all the way up to women in their eighties and nineties,” says Kaur. “I wanted that intergenerational lens. I want this to be reflective of as many Asian women as possible while also recognising there are lots of different layers and differences within there too.”

Kaur interviews the brown female founders of numerous social and activist initiatives to show the increasing spirit of sisterhood, both online and offline, developing among women from this demographic. “I think that’s really special, and that hasn’t been seen in any other time in human history, Asian women coming together like this,” she explains. “I really wanted to document that in this book, so it doesn’t get forgotten.”

Kaur is candid throughout, deeming domestic expectations as “patriarchal nonsense” and emphasising the importance of self-love prior to seeking love from others. “Marriage is not the only happily ever after,” she writes, while also advising spouses to share parenting duties equally, and adding that she was the one who proposed to her husband, instead of the other way around.

Rejecting binary models

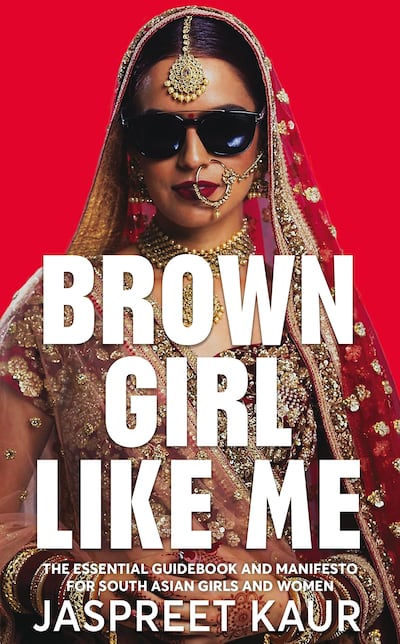

A portrait from Kaur’s own wedding, where she is dressed up in an ornate bridal outfit, with decadent jewellery and sunglasses, is the cover image of her book. “So often when we see Asian women being portrayed by the western mainstream media they are seen as meek, submissive and docile with that kind of that victimhood mentality, but I wanted to show how I see Asian women as incredible, strong, regal and fierce characters, and this image really encompassed that to me,” she explains.

By rejecting the traditional “shy bride” look while still appreciating elements of her culture, Kaur reaches a comfortable compromise, and she hopes her readers can achieve this too, rather than feel they have to choose between two extremes. She calls the “between two cultures” narrative an “outdated binary model", at times offensive and downright unrealistic.

“When you look at the western media, it’s always one or another. You’re either oppressed by your culture or religion or you completely abandon it. You’re veiled or unveiled, traditional or modern, and I wanted to show that for most Asian women, it’s everything along that spectrum, everything in between – all the messiness, the good, the bad and the ugly of managing these different things we have to navigate as [South] Asian women,” she says. “The way that we can undo and move away from this outdated binary model is through storytelling, through listening to these voices and perspectives.”

Kaur vocalises a concern that many brown women have about owning their culture while fitting into an increasingly globalised world: “As we become the next wave of brown mothers raising our children, is it possible to raise brown feminists [both girls and boys] without entirely rejecting our own culture and fitting into what western feminist standards dictate? Well, of course,” she writes.

“Our parents and grandparents’ jobs were to make sure we survived. It’s now our job to make sure we thrive.”