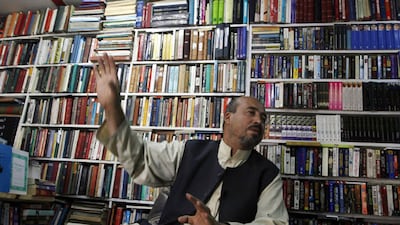

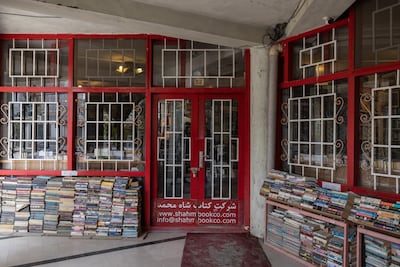

At a vibrant, traffic-jammed Kabul intersection, hidden in a courtyard behind stores selling camera equipment and colourful stationery, sits the shop of Shah Muhammad Rais, Afghanistan’s famous bookseller.

Founded in 1974 – shortly after a coup d’etat that ousted Afghanistan’s King Mohammed Zahir Shah and established the country’s first republic – the vast, two-storey shop holds more than 20,000 titles on Afghanistan, one of the world’s largest private collections of books on the country. It first became renowned with the publication of the international bestseller The Bookseller of Kabul, portraying Rais and life in the city.

As the Taliban have once again taken hold of Afghanistan, Rais says he refuses to worry, explaining that, almost half a century after opening his shop, he’s already seen enough regime changes, and is used to it. He’s determined to press on as usual.

“The Soviets were hardliners, too,” he tells The National. “They censored my books and put me in jail for a year for collecting decrees of Mullah Omar and other Jihadist newspapers that I obtained in Pakistan. When I got released, I cleaned the dust from my library and continued.” Years later, he says, American researchers came to read those “forbidden” titles.

“I will not stop my work, because it’s not against any government. I worked under the Taliban before, and I will obey them again, but I will also keep my business and I’m ready to accept the risks – even jail or torture. This store has grown and flourished over the decades; it’s a collection of history.”

While Rais left Kabul a few weeks ago for a trip to London, hoping to browse the world’s publishers for more books on Afghanistan, his staff stayed behind, now managing the store.

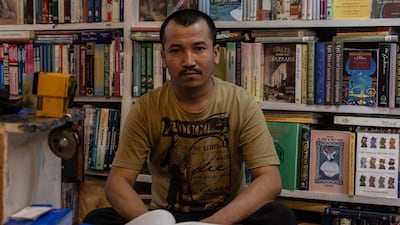

Unlike Rais, the young employees do not remember the previous Taliban regime and are nervous. “Of course I worry, because the Taliban are unfamiliar and scary to me,” says Khairuddin Youssufi, 26, who has worked with Rais for the past 12 years. “I have never seen them before.”

The shop, says Youssufi, provided his main source of education after he’d left school. “It became my second home. I learnt from the books and the bookseller,” he says, while sitting amid maps of Afghanistan, postcards and shelves stuffed to the ceiling with books and magazines in all languages. Some of the literature tells of the Taliban’s past wrongdoings, but also of atrocities committed by the American and Soviet invaders.

What Youssufi decries most these days is that the Americans took many of the “talented and literate people out of the country”, including most of his customers, many of whom were friends. “Bookselling is down now. People are poor and the economy is crumbling. Many are struggling to survive. There’s no money left for books.”

Since the Taliban entered Kabul on August 15, prompting the then-president Ashraf Ghani to flee with much of his cabinet – and hundreds of thousands of Afghans to run to the airport, adamant to get on a plane to anywhere – Rais’s bookshop has had only two customers.

For its employees, it still provides a lifeline.

Mahrajuddin Qiam, a father of three, 26, says his 10,000 afghani ($125) monthly income substitutes his previous job’s income at a government ministry; a job he has lost since the Taliban’s takeover.

“Right around then, I started working at the bookstore,” he explains. “Problems are increasing and people are running out of money. If the shop closes, I wouldn’t know how to support my family.”

On whether the new "Islamic Emirate" will be the same as the previous one – where books were burned and women denied access to education – Qiam didn’t want to comment. “If they are, they won’t fit the Afghanistan of the past few decades. Even the world will not recognise them.”

As for Rais, customers or not, the bookseller has big plans for the future. “I want to digitalise the whole store,” he says. “I’ve started to reprint rare and hard-to-find books and I’m filing others as PDFs or on the cloud. I want to make sure history is preserved.”