On the internet, you can live for ever. The data you’ve created – the agglomeration of every click, like, bookmark and share – will live on in its virtual home long after you’re gone.

What becomes of this data after you die? What is being done to it now? And does this digital patchwork of preferences constitute another "you"?

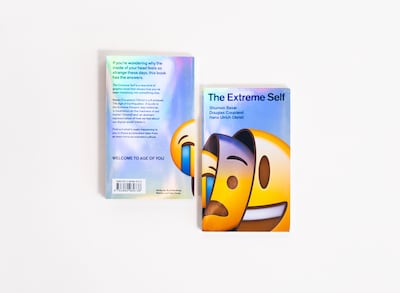

The Extreme Self: Age of You – a new book by Shumon Basar, Douglas Coupland and Hans-Ulrich Obrist – tackles these ideas in aphoristic prose paired with visual contributions from more than 70 contemporary artists, filmmakers, photographers, musicians and designers from around the world, including Anne Imhof, Cao Fei, Hito Steyerl and Trevor Paglen, as well as regional names including Raja’a Khalid, Rami Farook, Stephanie Saade, Lawrence Abu Hamdan and the artist collective GCC Group.

Its cover, the result of a collaboration between the authors and design duo Daly & Lyon, features a nesting doll emoji aptly named Matryoshkemoji – a beaming smiley as the exterior, housing an anxious one that finally contains a weeping face.

The authors are not technologists, but rather literary and art figures – Basar is a writer, editor and curator who contributes to several publications and has been leading Art Dubai’s Global Art Forum since 2007. Coupland is an artist and author whose notable novels include Generation X (1991) and JPod (2006). Obrist is a famed curator and an art historian, as well as the artistic director at the Serpentine Galleries in London.

Released last month, The Extreme Self follows the authors' 2015 book The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present, which deals with questions about our future in a world where technology keeps accelerating beyond our means to grasp it.

Both books draw from Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore’s The Medium is the Massage, published in 1967. The influential bestseller is about the impact the nature of media has on societies, and it also pairs text and images across its pages.

Following in McLuhan’s footsteps, the publications are collaborative in nature.

“We were looking for artists who not only document these societal changes, but also show us how we can actually liberate, in a way, the intercultural capacity of such technologies,” Obrist says. “I think we can only address the big topics of our time if we find new forms of collaboration, new alliances, and if we work from all disciplines.”

While The Age of Earthquakes includes more than 20 neologisms that label the changes in our tech-driven world, The Extreme Self centres on defining its title. Across 13 chapters, the book strives to explain how we as individuals have been, and continue to be, reshaped by the dominant technologies of our time, specifically the smartphone and social media. Along the way, it skims the surface of topics such as artificial intelligence, data rights, parasocial relationships, online radicalisation, disinformation and democracy.

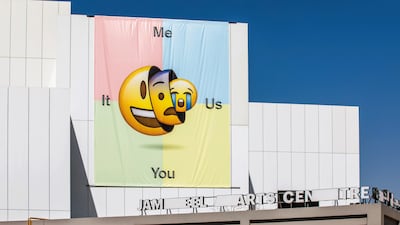

The authors have also turned the book into an exhibition, with Obrist primarily in charge of selecting the contributors. Titled Age of You, it is on view at Dubai’s Jameel Arts Centre until Saturday, August 14.

Age of You, as Basar describes it, is an “exploded book”, made mostly from vinyl board prints of its pages spread out across two galleries. The show’s highlights are its commissions and video installations, such as Trevor Paglen’s eerie Behold These Glorious Times! (2017), which shows a cascade of machine-learning images fed to computer systems to help them recognise objects and emotions.

There's also Audio Deepfakes (2020) by Vocal Synthesis, which plays computer-generated audio clips of famous figures reciting popular songs – Bob Dylan singing Britney Spears or Barack Obama quoting The Notorious BIG. Implied in these works is the potential for these technologies to become tools of manipulation.

At the core of the book and the show is the search for what the authors call the "Extreme Self".

“We needed to describe this thing that individuality is morphing into. You’re now becoming your Extreme Self … The idea of what constitutes you or me has now become so much more than what we thought 10 years ago, maybe even five years ago. If we keep extrapolating five years from now, 10 years from now, it’s just going to get even more extreme,” Basar says.

The authors ultimately don’t reach a precise definition, though who can blame them – the Extreme Self is ever-shifting, existing in virtual and physical space, not so much a character, but a condition. It manifests in a kind of disembodiment, where we export our interior lives to the Cloud and generate new selves online, with the internet reciprocating, weedling its way into our psyche.

One of the main symptoms, the book suggests, is a cognitive fuzziness – the heady feeling you get when you emerge from an internet rabbit hole or an unintended hour-long scroll through your social media feeds. This experience, shared by 3.8 billion of us who use smartphones or the nearly five billion with access to the internet, is a unique consequence of our online existence.

“In a loose sense, you could say the Extreme Self is that weird new thing we’ve all become inside our heads that we can’t still put our finger on,” Coupland says. “Anyone older than maybe 25 remembers that their brains once felt very different. The Extreme Self is what we turned into. People under 25 probably think of it as the everyday world.”

This generational gripe is echoed throughout the book, at times revealing a misplaced nostalgia.

“Anyone over 40 knows what classic individuality felt like. Now it’s almost a handicap,” the authors write. In another section, they state: “For a few centuries, smart people – who, being smart – more or less ran the world. The flattening effect of the internet has allowed the world be run by people with an IQ of 100. It is the revenge of the bell curve.”

The book promises to remedy all this. Its tagline states: “If you’re wondering why the inside of your head feels so strange these days, this book has the answers.”

By naming the Extreme Self, we may begin to understand it. The authors, for example, consider how, through data collection and algorithmic marketing, we are not only exploited by tech giants, but leave ourselves vulnerable to deceit.

“For thousands of years, earth’s resources have been extracted by bodies, most of whom were not free. But now, it’s our bodies, and our selves, being extracted. And … mostly we offer it up for free,” they write.

“What is the 21st century’s most valuable resource? That’s you and all your online behaviours, rich data sets, millions of metadata points,” Obrist explains.

This shift in value is a post-internet phenomenon, argues Basar. “I think that the 20th century was largely geopolitically constructed around the power of fossil capitalism, who had the coal, oil, gas … Today, it’s powered by what I would call emotional capitalism,” he says.

“The most valuable resources today are our emotions and how our emotions are coded, encoded and decoded through data. The whole galaxy of ourselves has been multiplied in exponential terms.”

Those who can access this bank of emotions can swing our feelings, and consequently our actions, in any direction – outrage, paranoia, fear or hate. More worrying is its consequence on political and democratic systems, as witnessed in election campaigns worldwide, or even the current public health crisis, with misinformation about vaccines rife amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Probably the worst aspect of human nature to be revealed [by technology] is the human capacity to take pride in ignorance,” Coupland says.

In the book, the authors state: “The breakdown of consensus-based reality is perhaps one of the most dangerous threats there has ever been to shared human experience," and ask, "Is there any turning back?”

The Extreme Self does lose its footing in some sections with simplified lines such as, “It’s actually astonishing how much the Left and Right have in common”, or terms such as “micro-othering” and “microfascism” – references to “microaggression” – that seem to trivialise violent movements that continually result in injustice and death. Here, the authors’ axiomatic style reaches its limits.

Nevertheless, The Extreme Self (and Age of You) are great catalysts for discussion, albeit at the risk of being passe, if only by the rapid nature of its subject. The book redeems itself in parts that offer more questions for readers and in its attempts to concretise our current relationship to technology with language. It may even open some eyes.

“As McLuhan said, ‘Art can be an early alarm system’. So we clearly hope that the book is a form of an alarm system,” Obrist says.

‘The Extreme Self’ is available at the Art Jameel Shop, online and at Jameel Arts Centre. Age of You is on view at Jameel Arts Centre until Saturday, August 14. More information at jameelartscentre.org