It’s funny to be reviewing a book about artists and motherhood when you are homeschooling: kind of like seeing an Instagram post of a party you are already at. “Gosh, that looks like a fun place to be,” you think. “Better than this vortex.”

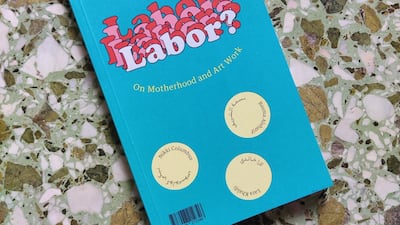

Why Call It Labor? On Motherhood and Art Work, published by the Arab funding organisation Mophradat and edited by its director, Mai Abu ElDahab, presents motherhood as vastly more complicated than a "fun place to be". Contributions by artists and curators such as Mary Jirmanus Saba, Basma Alsharif, Lara Khaldi, Nikki Columbus and Mirene Arsanios sketch out the structural problems facing mothers in the cultural arena. The "labour" in the book's title is a handy double entendre: the central problem is how working artists remain working even after they become mothers.

One consistent alarm bell is sounded throughout the book: of the pressure to keep up with the art world, socially and professionally, or risk being forgotten. Each mother recounts squeezing in the hours, in between naps and brief spells of downtime.

"If being a pregnant artist – and losing freelance work, funding and exposure opportunities as a result – has shown me anything," writes filmmaker Jirmanus Saba, "it's that the possibility of artistic success or even sustainability through hard work and perseverance is false. The art market is fickle, and its logic is based on sustaining its own growth."

What proportion of those are mothers is unclear, and this is what the article’s author, Hettie Judah, sought to uncover. Her research confirmed anecdotal suspicions: motherhood is frowned upon not only for the amount of time it leeches from one’s art practice, but also because it signals an uncoolness, a normativity, as one shifts from discovering new forms of radicality to scouring the school league tables and setting up piano lessons.

The book, published in both Arabic and English, makes it clear that the problem is systematic, relating to the general economic precarity of being a cultural worker and the art world’s incessant over-production. It’s a serious issue. In December, The Guardian published news of a recent report by the UK's Freelands Foundation on representation in the British art world. The article’s title itself is a spoiler: “Motherhood is taboo in the art world”. In the UK, the report states that 35 per cent of living artists represented by commercial galleries are women; the proportion of high-grossing sales at auction is smaller still at 3 per cent.

For cultural workers, motherhood is also a deterrent in jobs and opportunities, as small organisations often avoid women whom they suspect might imminently take maternity leave. Why Call It Labour? includes a conversation with one of the few cases in the art world where a mother successfully challenged an institution for discrimination. In 2017, Nikki Columbus entered into negotiations for a curatorial position at New York’s PS1 Contemporary Art Centre, part of The Museum of Modern Art. She was at that time pregnant, though the museum was not aware. By the time the start date and salary were finalised, she had given birth, and the museum withdrew its job offer. Columbus sued and received a settlement in 2019.

In the book, Columbus speaks to Lebanese writer Arsanios about the case, setting her experience against the broader landscape of legal rights and motherhood in New York. Both live in the city, and for Arsanios, the pressure to work is not only financial. She needs to maintain her income so she does not violate the terms of her 0-1 artist’s visa. In its orientation towards Arab mothers, Why Call It Labour? raises questions that are often excluded from white middle-class writings on motherhood, however well-intentioned they may be – such as the added wrinkle of visas and passports, and the work done to secure a child’s citizenship somewhere with better economic opportunities than one’s home country.

The perfect storm of professional and familial obligations – intense even before Covid-19 hit – is part of what makes Mophradat’s decision to devote a publication to motherhood important. It was relaunched under ElDahab’s leadership five years ago, and has shown itself astute in how it offers aid to artists and cultural workers, thinking around labyrinthine internal funding procedures at US museums, travel restrictions for Arab curators, and the kinds of grants that are useful.

Here, Mophradat wears its heart on its sleeve (Abu AlDahab, who has a young child, also contributes an essay) and recognises, from the ground up, the scale of the problem facing young artists who are also mothers.

Every mother needs a room in her house to be able to kick, scream, curse and write in, said French-Moroccan writer Leila Slimani at the Hay Festival a few years ago. That feels like a luxury momentarily scuppered by ongoing lockdowns, and I (selfishly) hope for more efforts to marry practicality and theory to succeed in confronting what we now call work-life balance.