For such an everyday ingredient, the lemon is a fruit of mystery. Its birthplace is unclear, its parentage unknown. Even the origins of the name a matter of dispute. Yet over the centuries the lemon has achieved global domination in the kitchens of the world. It is an essential ingredient in cuisines from Asia to Latin America, prized for its fragrant aroma and acidity.

There are few dishes from the Middle East complete without a squeeze of lemon. It would be impossible to cook the recipes of the great Egyptian-born Claudia Roden without a bag to hand, or following her instructions for preserving them in three different ways.

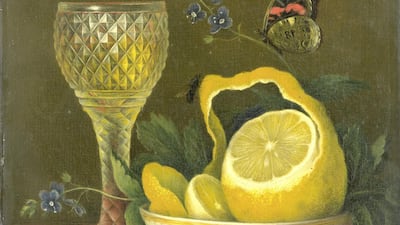

One aspect of the lemon's story is explored by Mariet Westermann, vice chancellor of NYU Abu Dhabi, and a historian of art from the Netherlands, where she was born. As a child, she was fascinated by the appearance of lemons, almost always cut with a curl of peel, in so many of the still-life paintings that were the staple of Dutch 17th-century art. "I always thought it was totally normal that they were there, because almost every still-life with a table had a lemon on it," she says.

As she will explore in her talk, The Emergence of the Lemon Twist in Dutch Still Life, which she will give on Wednesday, January 29 at NYUAD, the inclusion of a meticulously painted lemon was not an artistic afterthought, but the key to understanding society at the time. It was a luxury product, its appearance in the chill of northern Europe four centuries ago a triumph of science and botany. To have lemon on your table was a sign of having arrived in society, as much as a Mercedes or a Louis Vuitton bag is today.

Lemons in history

In the story of the lemon, though, this is quite a late chapter. The fruit is thought to have originated possibly in northern Myanmar or China, but more likely north-eastern India and Pakistan. It was probably a hybrid, a cross between the sour orange and the citron, a lemon-like fruit with a thick rind. Some kind of lemon-like fruit was cultivated as far south as the Arabian Gulf and may have been brought back to Europe via Greece by Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC.

The citron, and later lemons, were carried to ancient Rome, where they were a rarity, prized by the wealthy for both decorative and medicinal use. Mosaics featuring both fruit date back to Rome in the first century, while the remains of carbonised lemons have been recovered from the ruins of Pompeii, destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

It was the Arabs who took the lemon further west. The name may come from the Arabic laymun, although similar words are found in Old French and even as a corruption of the Sanskrit word nimbo by Arab traders. What is more certain is that the lemon was being referred to explicitly by the 13th century, when the Arabs had conquered most of what is now Spain, once known as Al Andalus.

Ibn Luyun, a writer, teacher and poet from Almeria on the coast of southern Spain, mentions them by name in his 14th-century Treatise on Agriculture. A century earlier, the first recipe for preserving citrus fruit was published in Cairo by Ibn Jumay, along with other medicinal recipes for lemons. Jumay, a physician in the court of Saladin, was Jewish, and would have been familiar with the use of another lemon-like citrus, the etrog, in the festival of Sukkot, where it is celebrated as one of four plants mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Even after the fall of the last territory of Al Andalus in the late 15th century, southern Spain remained an important area for lemon cultivation. Christopher Columbus is known to have taken lemon seeds on his first voyage of exploration in 1492, planting them on the island of Hispaniola, now split between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. After the Spanish conquered the Americas, lemon trees were grown widely, with Mexico now the world's second-largest producer of the fruit, behind India.

A sharp slice of luxury

Fast forward 200 years after Columbus, and it was the Dutch, newly independent from the Spanish empire, who were the rising power in world trade. The growing merchant class had a taste for the exotic when it came to spending their newly minted guilder. Cultivating citrus fruits became popular, with the wealthy adding indoor orangeries to their homes that would allow frost tender plants to flourish even during the harsh winter months, a burst of Mediterranean sunshine for when the days grew short.

Oranges were popular, not just because of the sweet fruit, but because their colour reflected loyalty to the new rulers, from the House of Orange, a title that originated from control of lands around the French city of the same name. But it was the lemon that really captured the imagination. Transporting boxes of the fruit by sea from the Mediterranean lands where they grew freely was impractical. Instead Dutch ships brought potted trees which could survive the short voyage north to their new indoor homes, while others were grown from seed.

While the lemon was a luxury, it was relatively easy to get hold of, says Westermann. "A good orangery might have 200 to 300 trees, and each tree could have between 50 and 100 fruits."

Part of the lemon's appeal was its diversity. Much of it was used for medicine, as a cure for nausea and sea sickness. Although vitamin C had not yet been discovered, it was found the juice prevented scurvy, a disease that ravaged crews on long sea voyages.

Lemon peel could be candied with sugar imported from the plantations of the New World. Blossoms perfumed water or were dried for their scent. The leaves were chewed or the fruit reduced with more sugar to make pastille sweets. "Some of the recipes are so clear I could probably make them today," says Westermann.

It was inevitable that the lemon would become integral to that other Dutch status symbol, the still-life painting in which objects, everyday and exotic, were grouped using almost photo-realistic detail. Still-life drawings were produced by the hundreds of thousands in the 17th century to hang on the walls of middle-class households. And no still-life was complete without a lemon, a chance for painters to demonstrate their skill, especially with the curls of peel, and purchasers to display their sophisticated tastes.

In 2016 American researchers calculated that a lemon appeared in 51 per cent of Dutch paintings by the middle of the 17th century. "These painters never set out to paint the economy," says Westermann, but the repeated motif of the peeled lemon in so many works was a symbol of the predominate interests in Dutch society at the time; commerce, natural history and art. New styles of painting would reduce the popular appeal of the still-life by the 19th century, while the arrival of the railway and the steam ship would slash import times and turn the lemon from a rarity to a kitchen staple.

Today, lemons are grown for export in more than a dozen countries on four continents, and with an annual harvest of more than 13 million tonnes, one can be purchased for only a few dirhams. Still, as any good cook will tell you, lemons remain the height of good taste.

The Emergence of the Lemon Twist in Dutch Still Life takes place Wednesday, January 29 at 5.30pm at NYU Abu Dhabi Institute