It seems quite incredible that even as the world continues to come to terms with the ravages wreaked by the coronavirus, 64 countries have sent participants to take part in the 17th Venice Biennale of Architecture.

In fact, it is nothing less than a miracle. And this is no virtual manifestation, but a real-life event, which will run for the next six months until November 21, with the prospect of 8,000 daily visitors to Venice’s grand venues, the historic Giardini gardens and sprawling shipyards of the Arsenale, all under sensible sanitary control and social distancing.

The theme of this year’s Biennale is itself an apposite call to arms that has been enthusiastically embraced by everyone.

Hashim Sarkis, the Lebanese curator of the 2021 iteration, asks the question, "How will we live together?".

"It may be a coincidence that the theme was proposed a few months before the pandemic, but many of the reasons that initially led us to ask this question – the intensifying climate crisis, massive population displacements, political instabilities around the world, and growing racial, social, and economic inequalities, among others – have led us to this pandemic and have become all the more relevant," he says.

"We can no longer wait for politicians to propose a path towards a better future. As politics continue to divide and isolate, we can offer alternative ways of living together through architecture.”

Postponed from last year but now displacing the scheduled Biennale of Art, this newly-opened Biennale of Architecture is attracting attention, not just because it is the first global cultural event since the beginning of the pandemic, but also because there are some notable developments.

Many presentations in the venerable National Pavilions of the Giardini that have established newer homes in the raw, semi-industrial warehouses of the Arsenale, are more exciting and innovative, and catching people’s attention.

And this edition has certainly been marked by a strong and influential presence from the Arab world, with National Pavilions representing the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon and Iraq, as well as a Palestinian presence, albeit participating in the Central Pavilion curated personally by Sarkis.

The Biennale, as always, is not without a buzz of controversy. Over the last few iterations, the national presentations hawve increasingly blurred the line between the Architecture and the more prestigious Art Biennales, a renowned event that dates back to 1895.

This week, Marino Follin, former rector of IUAV, Venice's prestigious architecture school, said that "this Biennale is everything, but it is not architecture", and there is an undeniably growing presence of artistic works, poetry, music, video and avant-garde installations alongside the more classical building maquettes that once dominated the pavilions.

The UAE commissioned a renowned art photographer to exhibit creative images to complement its innovative construction module. The Chile pavilion is dominated by paintings, Egypt uses reportage photographs, Brazil presents videos, while stunning African sculptures dominate the As New Households exhibition at the entrance of the Corderie section in the Arsenale.

Rushing from one pavilion inauguration to the next on the opening days, Sarkis takes a more even-handed approach.

"It is something of a miracle that this has all come together, and I am happy with everything because as you look all around, people seem happy – the participants and the visitors – and for a beginning, after all that has happened in the world, that is the most important thing," he says.

The National Pavilions of UAE and Saudi Arabia sit physically side by side in the Arsenale, but have taken very different approaches to the theme.

While UAE curator Wael Al Awar has overseen Wetland, a groundbreaking project to create environmentally-friendly cement made from recycled brine waste, Saudi Arabia, for only its second participation at the Architecture Biennale, has put together a team of new-generation architects and curators from Brooklyn to examine the theme of Accommodations, through the lens of quarantine, from the current times of face masks to historical enclosures.

For the moment, the vast hall in the Arsenale's Artiglierie building slated to house Kuwait's exhibition, intriguingly entitled Star Wars, is bare and empty, as Covid-19 issues in Kuwait itself have forced a postponement of the installation until this summer.

Next door though, dynamic young architect Noura Al Sayeh has supervised a team of local Venetian workers to install her co-curated show, In Muharraq. This pays homage to Bahrain's Unesco World Heritage Pearling Path by constructing a giant artificial plateau that poses the question of whether coral stones, cars and humans can sustainably cohabit today.

This is the first-ever presence in Venice for Iraq, and it has not been simple, with the original location for the National Pavilion in a traditional Venetian boatyard falling through at the last minute, replaced with a temporary presence in the Oceanic collateral show housed in San Lorenzo church owing to precautionary measures.

But this is certainly not dampening the enthusiasm of the pavilion’s irrepressible artist Rashad Salim, who has already become a distinctive figure around Venice with his traditional headgear and a carved gondola that he carries everywhere.

Salim is determined to make presentations throughout the six months of the Biennale and to create a dialogue with the city as he presents Ark Re-imagined, which focuses on the Arch of Ctesiphon, a 1,700-year-old arch in Iraq which needs preservation.

“For Iraq’s first time here in Venice, ours is very much an expeditionary presence,” he says. “Being expeditionary affords us both flexibility and living urgency as we pose the question, how could the Arch [were it built] have been constructed in its time and place?

"The answer is an attempt to understand how we got to where we are, what we have lost along the way, and what may be good to recover and regain including our connection with the ecology that inspired our culture and, through the climate change event of the ancient Flood, gave birth to our civilisation," he adds.

Over in the Giardini, the Across Borders section of the Central Pavilion addresses border control issues at the Palestinian exhibit which looks at how Israel's control of the border impacts farmers in Gaza. In contrast, just across the gardens, the Israel Pavilion invites visitors to discover its provocative presentation Land.Milk.Honey, which examines how plenitude can be achieved through reciprocal relations between humans and animals.

Egypt possesses one of the oldest pavilions in the Giardini, inaugurated in 1932, but is presenting an unconventional, non-architectural exhibition called The Blessed Fragments. Created by photographer Mohamed Al Hosary, 26, it is a series of eye-catching black-and-white Pop Art portraits of what the curator describes as “the common people’s true value, unity, the power of integration and the emerging balance”.

That is in response to the theme of How will we live together?

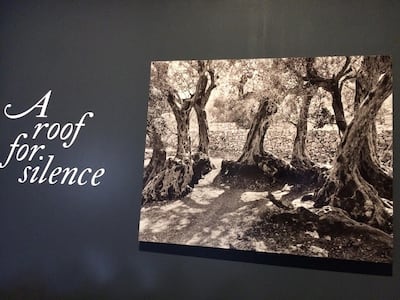

The Lebanese National Pavilion is located outside the Giardini and Arsenale sites, in the quiet Venetian neighbourhood of Dorsoduro. Despite the recurring troubles in Lebanon, its citizens seem to thrive at overcoming problems and their National Pavilion, A Roof for Silence, aims to raise awareness of the rehabilitation of the damaged architectural and cultural heritage of Beirut.

Hala Warde, who realised Louvre Abu Dhabi with France's celebrated architect Jean Nouvel, has created an intense, emotional installation in the serenissima's ancient Magazzini del Sale, the salt warehouse on the Giudecca canal.

It utilises the symbol of 1,000-year-old olive trees through not just architecture, but also painting, music, poetry, video and photography.

And to emphasise the delight at being present at the Biennale, Lebanon was one of the few pavilions to organise a festive vernissage on a floating canal pontoon outside the pavilion, complete with music by a DJ, home-baked zaatar flatbread and special Lebanese lemonade.

All that was missing in this time of social distancing was dancing, but the positive atmosphere most definitely augurs well, not just for the future of this Biennale, but the future of Venice itself, the economy of which is desperate for the return of visitors in a post-lockdown, vaccinated world.