Geneva Museum of Art and History is celebrating, on the centenary of his death, a little-known figure who became instrumental in saving and highlighting the history of Arabic inscriptions.

Max van Berchem, a Swiss philologist, was born in Geneva, Switzerland, to a patrician family, and travelled to the Middle East during the height of European interest in the region. While this period in art is best known for the Orientalist paintings it produced, van Berchem's contribution was quieter, nerdier and probably more long-lasting.

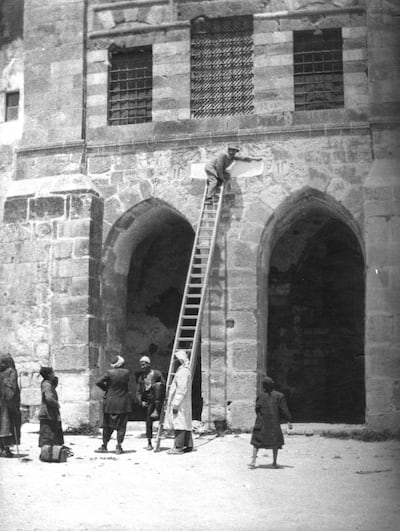

He is known as the inventor of Arabic epigraphy, or the study of Arab inscriptions, and produced, with a vast network of mainly European and Turkish scholars, the Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum. Interrupted by the First World War, the project exceeded van Berchem's lifetime. It today stands as a compendium of stone inscriptions found mostly in Palestine, Egypt, Syria and Jordan – many crumbling owing to age and neglect.

Van Berchem died before the project could be completed, and his widow donated many of the objects he collected to the Geneva Museum of Art and History. Other books and writings went to the Geneva Library, and both entities have collaborated on a show, titled Max van Berchem: The Adventure of Arabic Epigraphy, on view at the museum.

“He realised the necessity of saving part of a culture that was slowly disappearing,” says Marc-Olivier Wahler, director at the Geneva Museum of Art and History. “He was not the only one to try to save all of these inscriptions, but he did it in a way that allowed many people to participate. He was in contact with everyone – even Lawrence of Arabia – and the show relates to this network.”

Van Berchem studied Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic and Farsi, and had initially been interested in Greek culture, but two trips in 1886 and 1888 to Egypt and Syria, where he saw the perilous state of numerous inscriptions, inspired him to help conserve them.

The exhibition has been years in the making – and comes at a febrile point for a show relating to fragments of cultural heritage taken from the Middle East, as the discourse around restitution claims intensifies. But the academic work done for it has revealed more information about many of the items in the collection.

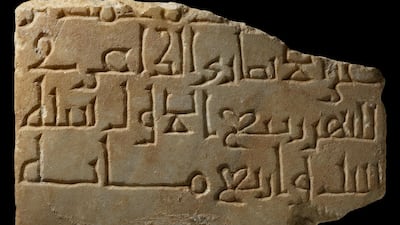

One stele – the only stone Arabic inscription in the museum’s collection – has an uncertain provenance. The museum knew it dated to 1015 and was purchased in 1922 in Basel, but it did not know the exact site of origin. Some guesses included Syria, perhaps Palmyra, or Petra in Jordan – two major sites of archaeological excavation. Preparation for the show revealed that in 1893 van Berchem had taken a rubbing of that exact stele, which was later taken and sold in Basel. The discovery locates it in Ashkelon, just north of the Gaza Strip. Other objects on view are inscribed brass torches, bowls, pottery and manuscripts.

The Geneva Museum of Art and History, which has about a million objects in its collection, is going through an ambitious overhaul. It is in the midst of a decade-long project that will expand its exhibition space from 14,000 to 28,000 square metres, and build a new wing of the museum.

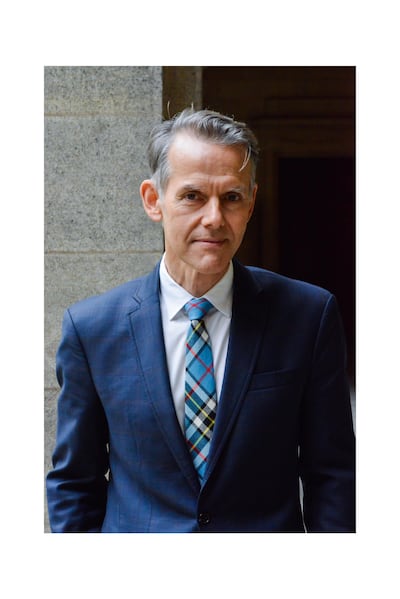

Equally important, last year, the museum tapped Swiss curator Wahler as head. He is a veteran curator who has been involved in ambitious institutional experiments and contemporary projects over the past 20 years. He worked as head of the Swiss Institute in New York, at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and he co-founded the Centre d'art Neuchatel in Switzerland.

Throughout, he says, his goal has been to bring in new audiences to the contemporary art sector. While at the Palais de Tokyo, he extended the opening hours until midnight and found the museum became a popular site for dates, something British newspaper The Guardian highlighted in 2009.

"I thought, you know, I tried to make radical exhibitions – and that's what they have to say about Palais de Tokyo," he recalls. "But then I realised, actually it's great, you come to Tokyo hoping you will fall in love and that's the best way to come to a museum. People come to an institution 10 times and by chance, the 11th time you would stay in an exhibition and then discover something you wouldn't imagine."

Wahler says the Geneva Museum of Art and History will be his ultimate test: a sedate, classic museum in a conservative Swiss town. Part of his plan is to mix academic exhibitions, along the lines of van Berchem, with more radical ones. The contemporary display currently up is by Viennese artist Jakob Lena Knebl, who used the scenography of the museum to emphasise the domestic or useful function of art objects, which is usually overshadowed in museum displays. Instead, Knebl has placed the artworks in disjunctive domestic settings, such as a marble bust in a shower cabin or a Sphinx appearing to sit on plush red seating.

“If you work at the ICA, or the Palais de Tokyo or Ps1, they’re embedded with contemporary art,” Wahler says. “But to be radical with art from antiquity or the Middle Ages and nowadays, for me, that’s the next level of challenge.”

Max van Berchem: The Adventure of Arabic Epigraphy is at the Museum of Art and History in Geneva, Switzerland, until Sunday, June 6