This month marks a year since the coronavirus pandemic initiated a series of global shutdowns across art organisations. The immediate effect of the pandemic was a swift shift to digital programming: exhibitions became walk-throughs; fair booths became virtual viewing rooms; and Q&As became video chats. The amount of material made available online, as well as its uptake among the public, was overwhelming, fuelled perhaps by adrenalin and sublimated panic.

That flurry of initial activity has subsided, but the “new normal” is still emerging. What have been the effects of a year’s worth of online programming on art organisations, artists and audiences – and specifically for the Arab world?

One major change is an appreciation of the digital sphere as a separate strand of curatorial thinking – an investment that has long been overdue. Dedicated digital programming has been patchy across art organisations, driven mostly by individual curators or at venues that have deliberately looked at new media.

Few museums have made formal departments, but that will likely shift. "The digital sphere has always had this sort of secondary position, and people didn't take it as seriously as they should," says Krist Gruijthuijsen, director of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. "It came with very cliched mediation formats. But in the last year, we have sped up the respect that the digital sphere deserves."

KW will launch a digital department at the end of April, which will be overseen by curatorial hire Nadim Samman. The website will adapt many exhibition procedures from the physical realm, such as shows being time-limited and part of tours.

“Exhibitions will only exist at a certain moment on our website, and then they will travel to another institution’s website,” Gruijthuijsen explains.

“So there’s an interest in trying to understand temporalities when it comes down to digital representations. I believe in accessibility, but also in the beauty of missing out.”

In Dubai, the Jameel Arts Centre is likewise expanding their digital platform. "We're building up resources online [audio, video, written] so that we leave a legacy of research and context," says Antonia Carver, head of Art Jameel. "This is reflected in our current approach to the school's programme – we don't give virtual tours of IRL exhibitions, but we showcase particular in-depth works of art, and debate them through online classes," she says.

When restrictions fully lift, UAE schools visits will return in person, but the museum will continue to offer online classes to schools and universities farther afield.

Jameel is also commissioning more digital work. Last April, the organisation shifted tack quickly in response to the pandemic and changed its 2020 commissioning call, a competition based each year on a different medium, from painting to digital technologies.

Its current online exhibition is the result of this commission: Nadim Choufi's sci-fi video The Sky Oscillates Between Eternity and its Immediate Consequences (2020), which the artist in Beirut worked on under the difficult conditions after the port blast.

Expanded audiences and new archives

As online programming expanded, so did its audience. Zoom panels and lectures became the norm, and an art public at home became familiar with testing out new areas of interest.

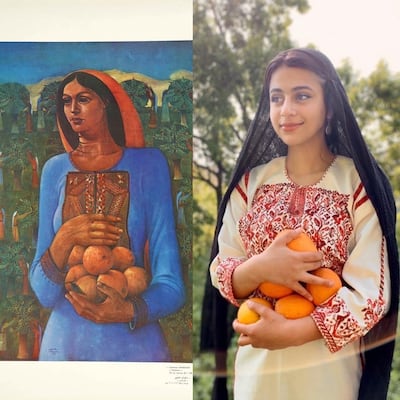

This has had a knock-on effect in the Arab world – where many organisations already had a jump-start with regard to digital programming because of visa and travel restrictions. The Palestinian Museum, in Birzeit near Ramallah, has always made digital outreach integral, but is now giving it broader attention.

"From the beginning, we have been a transnational museum," says Adila Laidi-Hanieh, the museum's director general. Substantial portions of its core audience cannot visit the museum, either because they are the Palestinian diaspora or are unable to travel from places such as Gaza within the occupied territory. The museum has invested significantly in Palestinian Journeys and Palestinian Archive: the first an interactive platform on Palestinian history, and the second a collection of photographs, film and audio material from Palestinian families. Both live as permanent curatorial projects online.

The museum expanded its audience during the pandemic with a number of popular online campaigns, Q&As and exhibition tours.

“A lot of people from outside Palestine now follow us,” says Laidi-Hanieh. “We have lots of participants from Tunisia, from Bahrain. A winner from one of our Facebook contests was from Aleppo. We have greatly increased the numbers of people who see us virtually.”

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi's Online Cultural Majlis, the virtual version of the in-person talks that the Sharjah collector and art historian has been running since 2019, also shows that niche disciplines are benefiting from the lower barriers to online entry.

About 300 attendees logged in for a discussion with Minister of Culture and Youth Noura Al Kaabi, and about 250 for Palestinian painter Samia Halaby – an uncommon level of popularity for talks in the lamentably small field of Arab art. But for Al Qassemi, the contribution of Online Cultural Majlis is less in its viewership figures than in the archive it forms.

“Online programming has been amazing for Arab culture,” he says. “The fact is that we lack documentation. And what the Arab world is doing with the pandemic is leapfrogging decades of missed opportunities to document and to interview artists.

“We didn’t have many opportunities to document because it requires costs: you had to travel, take a camera, get a visa, buy a recording device. But with Zoom, you’re leapfrogging all this bureaucracy, you’re leapfrogging the cost, you’re leapfrogging the logistical challenges.”

Some of the artists interviewed on the Online Cultural Majlis have made few public appearances, such as Jordanian artist Hind Nasser and Palestinian painter Ufemia Rizk, who were both pupils of Turkish artist Fahrelnissa Zeid. And, because many of the artists who were important to Arab modernism are now older, the need to archive their voices is becoming more urgent.

Reimagining online viewership

The attendance figures for Online Cultural Majlis have dropped since the early days of Covid-19. This is partly because the pandemic has had its own temporality.

“The speed at which we, as a global arts community, went from digital-giddy to Zoom fatigue was so compressed,” says Carver. “It barely outlasted the initial [stay-at-home] period of three months.”

One of the most enduring effects of online programming might well be a recalibration of the idea of virtual public. This is something another popular talks platform, Afikra (from the Arabic slang word for "on second thought"), has actively tackled.

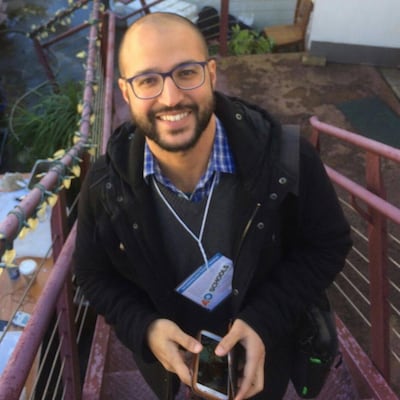

The platform has been running for seven years, first out of founder Mikey Muhanna's Brooklyn flat, and then in a number of satellite locations including Dubai, Washington, London and Beirut, where Muhanna now lives.

The pandemic accelerated plans he already had in place to go digital, and last March, Muhanna began hosting weekly lectures online. The agenda evolved to include two additional weekly conversations, with personalities such as the Syrian-American poet and rapper Omar Offendum and French-Tunisian artist eL Seed, and then expanded further with shorter, 15-minute presentations. In August, Muhanna – who has worked for Teach for America and Morgan Stanley – took another step back and publicly asked the Afikra community to speak to him one on one.

“It sounds maniacal, but I had about 200 phone calls over the course of three weeks,” he says. “I was completely exhausted. But if you say you’re going to build a community organisation, you need to meet the community.”

Community, in fact, was the main takeaway from his discussions: Afikra had become a network where people saw familiar faces, struck up side conversations, and traded perspectives. Muhanna is now launching a website redesign that will encourage this kind of interaction, allowing members to build profiles and contact others on the site.

“There are two parts to our mission,” he explains. “The first is to cultivate curiosity. The second is to build community. There’s no shortage of lectures available. I don’t even have to get out of my chair – I can just go on YouTube, and find hundreds of lectures about art history and culture. What’s missing is an invitation to contribute to the discourse, and become a producer of knowledge and part of a community of folk who are saying: ‘Yes, I want to listen to you.’”

Once people return to events and exhibitions in person, the challenge for art organisations will be how to retain the community they've attracted – and how to pay for it. Yet, the financial fallout of the pandemic is yet to fully hit many museums, and digital programming, with its lower overheads, might well remain central for sometime yet.