“There’s a framing to Palestinian art internationally. People want to see the suffering,” says Yazid Anani, one of the curators involved in the Qalandiya International biennial. “They want to see the wall, they want to see checkpoints, and they want to see the Israelis. Less has been done on the status quo of the Palestinian Authority and its troubling construct.”

Two weeks ago, the Qalandiya International opened across the Occupied Territories with the theme of “Solidarity”, bringing together exhibitions from Jerusalem and Ramallah, Gaza and the Golan Heights.

This year, the biennial refused all international funding, and all nine organisations that participated in the event contributed to it themselves. Each exhibition was asked to address that charged Palestinian term of “solidarity” – a theme that, ironically, yielded a variety of responses.

“We didn’t want to romanticise ‘solidarity’,” says Reem Shadid, who co-curated one of the Qalandiya exhibitions, Debt, at Ramallah’s Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre. “What does it mean? It’s such a personal sentiment. In some ways, it’s no longer collective.”

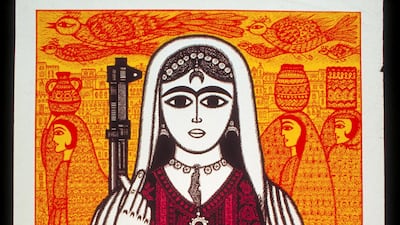

Shadid and her co-curator, Yazan Khalili, considered debt as a means of structuring human and artistic relations, both in terms of what is owed financially and emotionally. “You owe a lot to your family, for example,” suggests Shadid. For Lydda, a show examining a garden city from the 1940s that was planned for British colonialists, Anani explored a site he is unable to visit. A show at the Palestinian Museum looked at how traditional Palestinian embroidery became part of the symbology of struggle.

But if the responses were varied, one clear picture of the Palestinian art scene emerged: one that is moving away from the first generation of the country’s artists who created committed art in line with Palestine Liberation Organisation goals. They’re also, and more slowly, moving away from the second stage as well, the post-Oslo Accords era when Palestinian art gained currency abroad and when the NGOs began funding the nascent Palestinian state. According to Antonia Blau, who is researching a PhD on European cultural engagement in Palestine, foreign investment now supplies the infrastructure for most of the Palestinian cultural and governmental institutions.

“With the theme we said let’s go back to the First Intifada,” explains Anani. “We wanted to be independent of the Israelis at that time. We wanted to grow our own food. We wanted to produce our own knowledge.” Now, he continues, “we are back to a stage where we are so dependent on the Israelis for our political dealings, through the Palestinian Authority. The market is inflated with Israeli products. We don’t do anything about our own security – we cannot do anything except through the Israelis.”

The current espousal of “Solidarity” means not only solidarity against the Israeli occupation, but self-sufficiency for the Palestinian cultural scene.

Hipster Ramallah

Part of the reason that artists want to move away from the committed, or anguished, vision of the Palestinian artist is the relative normalcy of life in Ramallah, the de facto capital of Palestine. Boutique hotels cater to a handful of tourists. Bars serve local brews; at the Garage, across from the Sakakini Centre, artists spilled over from the Qalandiya opening onto mismatched chairs and reclaimed benches, and smoked late into the night.

The occupation is ever-present, but artists and curators want to approach it as it is: not as a symbol, but in the myriad, complex, and inflexible ways it controls daily life.

According to Shadid, who grew up in Jerusalem and is now deputy director of the Sharjah Art Foundation, the fact of the occupation is “everywhere. You can’t escape it.” It presents itself in numerous logistical challenges. For Debt, she and Khalili, an artist and director of the Sakakini Centre, couldn’t ship work in, both because of their low budget and restrictions on what can be sent into Palestine. “We’re just used to it,” Khalili says. “We don’t even send letters of invitation any more. Khalas. We know they won’t go through.” Instead, artists doing projects with the Sakakini come on tourist visas.

“It’s always in the back of your head,” says Rana Anani, project co-ordinator of Qalandiya. “It means you don’t travel to other cities in Palestine. You don’t show your children the country. You get used to just staying in Ramallah, because the process of applying for a permit is too complicated – and humiliating. You drive two hours out of the way to avoid a checkpoint. It’s there all the time.”

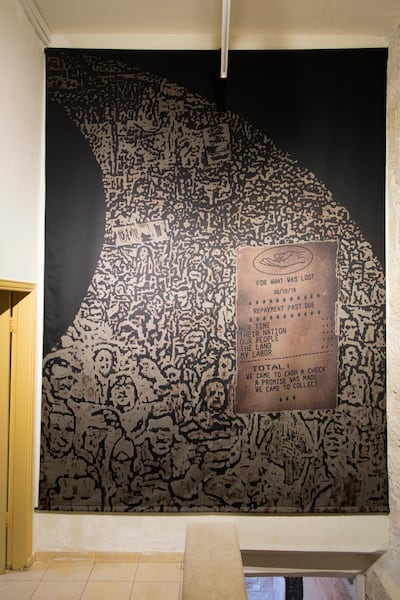

The system of permits meant that the Qalandiya's "solidarity" was a privilege open only to visitors: most of the organisers and local audience couldn't travel to all the sites. Many of those from Ramallah saw the Jerusalem shows through Instagram; the excursion to the Golan Heights was similarly out of reach. Only those Palestinians born inside the 1948 borders, and whose parents never left, have freedom of movement throughout Israel. The restrictions affected the way work was shown. At Debt, Shadid and Khalili, who have known each other since they were students at Birzeit University, asked artists to re-imagine existing works as posters, which they could print in Ramallah.

Walid Raad's Walkthrough, Part 1 (2013/2018) was originally an enormous installation and performance. It looked into a venture in Dubai that set up an artists' pension trust. For the Ramallah show, Raad pared back the project to a poster, translated into Arabic for the first time and free for visitors to take away. "What did it mean for Walid to make this in Palestine?" Khalili asks. "Although we were bringing already existing works, none of them came as it is. Every work went through a certain kind of transformation to cross this threshold, to be in Palestine."

Because the logistics were so complicated, curating the exhibition required numerous conversations with artists, and the show itself benefited from it: Debt coaxed from its artists a series of particularly thoughtful answers.

Restrictions on travel were the impetus behind Yazid Anani’s Lydda exhibition at Birzeit University, part of the “Cities” project that the architecture professor and Qattan Foundation curator has been exploring since 2009.

“The Cities exhibitions connect the divided cities in Palestine, whether in Israel or the Palestinian community in Gaza or the diaspora,” he explains. “My students at Birzeit didn’t know the other cities in Palestine – they only knew the superficial, popular cultural symbol of the city. For example, Nablus – knafeh. We thought, how can we excavate important knowledge that is not about the larger narrative of Palestine, but about the cities themselves? We started researching Jerusalem, Ramallah, Nablus, Jericho, Gaza. We tried each time to look for knowledge that would help us understand what has been marginalised in our own history.”

Lydda was planned as a garden city in the 1940s to host British colonisers. Unearthing this past, the city’s planned ethnic segregation emerged as a forerunner of the current segregation between Israelis and Palestinians. “I cannot myself go to Lydda,” Anani says. “But the international artists, and artists from Jerusalem who have a passport, they can go there physically rather than only learning about it through talks.”

Solidarity, now, means self-sufficiency

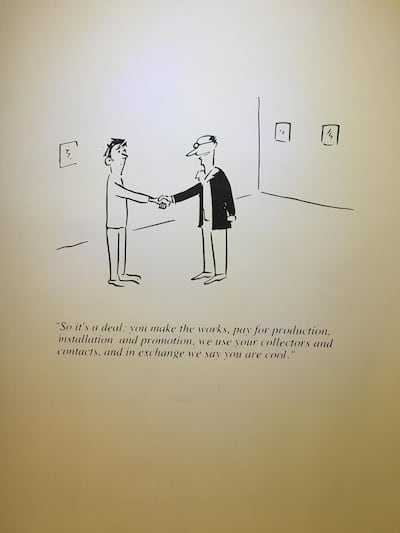

Another question prompted by “Solidarity” was: what is the art scene doing well? What does it need more of? The biennial organised a number of talks and conferences on this topic: it was a moment of collective self-evaluation. As ever, answers were fractured and split, but building space for critical art appears the focus for many. “This is not the place to be an artist,” says Khalili, whose own practice as an artist shares space with his other role as director of the Sakakini. “Here you cannot think of art only through galleries and the art market. One has to produce this alternative to it. At the Sakakini, it’s about producing that alternative. We work on producing art that cannot be commodities.”

I heard from more than one artist that their artwork now is building institutions, whether real sites, like the Fateh Al Mudares Centre in Majdal Shams, or projects that blur the line between artwork and museum. (Two major institutions also recently opened after substantial delays: the Palestinian Museum and the AM Qattan Foundation Cultural Centre.) In Debt, Khalil Rabah, for example, showed part of his long-running Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind, which he began in 1995. In 2004, the Ramallah artist auctioned off parts of the Wall that the Israelis erected around Jerusalem and the West Bank – a pointed performance about the commodification of Palestinian suffering that the audience took seriously, and started bidding real money for, even though Rabah had meant it in jest.

In Debt, as well, the New York/Armenia-based artists Rene Gabri and Ayreen Anastas made a proposal for the Communist Museum of Palestine, as a kind of crowd-sourced, dispersed institution. They offered tiles reading the ‘Communist Museum of Palestine’, which visitors could sign up to take. Next, Gabri and Anastas will assemble a collection by asking artists to donate their works, rather than buying them, and will place the works in the homes of Palestinians who have taken the tiles from the Sakakini. The tiles are effectively a logo – if members of the public are walking by and see them, they can stop in to view the works.

“Each context creates a situation – even through very negative conditions like occupation, colonialism, settlers – that makes something possible that wouldn’t even be imaginable elsewhere,” Gabri tells me. “We would like to generate another possibility of thinking about art and the destiny of art, about the place that art is housed, literally and figuratively, and to critique some historical elements of the museum.”

While we were speaking, a visitor knocked some tiles off the table and they shattered on the floor. Anastas glanced over and shrugged. “It’s just a tile.” The project is about the people.

_________________________

Read more:

Booklava: the audiobook platform bringing the best of Arab literature to the masses

Abdulqader Al Rais is painting his own narrative at his Paris retrospective exhibition

Woman who bought shredded Banksy will keep it

_________________________