My relationship with Marwan Kassab-Bachi, known simply as Marwan, began with Rudolf Springer, the vivacious, celebrated art dealer and gallerist, who oozed charisma and had a flair for spotting artistic talent.

A kingpin of German and international art, Springer had established his namesake gallery in his parents' home in 1948 in Berlin, showing artists such as Hans Uhlmann, Andre Masson, Alexander Calder, Victor Vasarely and David Hockney, among countless others. For decades, Galerie Springer served as the link between German art and the world, presenting the work of several internationally recognised artists.

Springer exhibited pieces by the young front runners of the New Figuration movement of the 1960s; these included Georg Baselitz, Eugen Schonebeck and Marwan. Their spirit geared towards informal, non-figurative abstraction and looked towards colour. Marwan came into contact with them shortly after he arrived in Berlin in 1957 from his native Syria for a scholarship at the Higher Institute of Fine Arts. It was a new post-war environment, and although Marwan found himself adopting German thought and identity, he always felt like an outsider. He shared a studio with Baselitz, and their aesthetic and thematic methodology involved a very existential approach to the body and the human being.

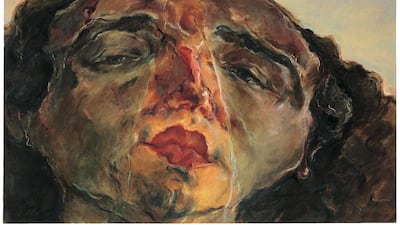

I opened my gallery in Kiel 1985, and Springer was keen on collaborating with me on a project. As fate would have it, the introduction to Marwan happened three years later. I remember being so impressed by his huge paintings hung all over his smoke-filled studio, and also recall that as a character, he was a curious combination of modesty and arrogance. Marwan was not conceited per se, but positioned himself as important. I gave him a show in 1989, and by that time, his paintings of faces had become extremely abstract.

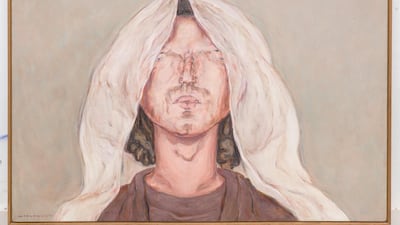

Marwan began focusing on the face – mainly his face – after the 1960s. He looked to the face as a landscape, a mirror of the soul and explored it with a Sufi attitude in his desperate desire to reach the inner self. No doubt, the Sufi slant stems from the artist's years studying Arabic literature at Damascus University where he read Sufi philosophy.

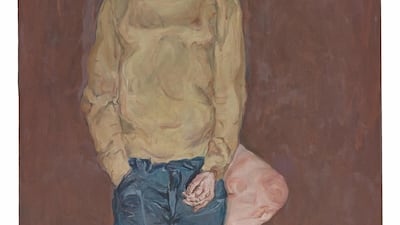

Looking back, I would say he knew then that the face would be his career’s commitment. Marwan had taken a firm decision on a subject at which he persisted and since then, exerted effort on its construction and deconstruction. All at once, the paintings are beautiful, violent and terribly gripping. In addition to being a serious consideration of portraiture, beyond the face Marwan explored the body in a manner that recalled the Renaissance attitude, adding German expressionistic elements and commitments to it.

The face came to be a relentless avenue to venture deeper; Marwan sought the essence of the nature of man. It was clear this was a struggle of the self. A troubled fellow, a tortured soul, thankful in a moment and forgetful in another, Marwan was without doubt a difficult character. He grappled with everything and everyone, save for his wife, Angelika, his former student who, as her name intimates, gave him serenity.

Students he taught at the Higher Institute of Fine Arts in Berlin between 1980 and 2002 also gave him happiness. They adored him and he gave them his undivided attention, especially the Baalbaki family of artists, Ayman, Osama and Said, from Lebanon.

No painting by Marwan makes you laugh or smile and, indubitably, they are not easy sells. The torment is crystal clear, and I came to sense that it was embedded in his DNA. All the same, I loved his work then and now, and knew what to select. And like any master, Marwan would not allow a work to exit the studio if he did not feel it was perfect, complete, sublime. He wanted to paint my face, but as with many things, life happened as did so many “next times”.

One of Marwan's deep concerns was Syria's political strife. Though he lived in Germany for almost 60 years – much more than he had in his homeland – Syria was never far from his heart and mind. The events back home over the years broke him, especially the 2011 uprising. After he first arrived in Germany, he made regular trips to Damascus and wrote a diary entry every day. His paintings focused on those who had died for their political beliefs and, yes, I would say he was political enough for him to receive some warnings in the 1960s from Syrian officials. Afterwards, he stopped painting such works.

However political his early paintings may have been, his trajectory had always been incredibly existential. Marwan questioned sexuality, the body, and from the 1970s, the faces became exceedingly abstract, and increasingly centred on the soul. In the 1970s, he was given a marionette that he kept against his window. It never ceased to fascinate him, and he continued to paint it over and over again, layer after layer. Many of his paintings are dated over several years because Marwan would return to them time and again, layering and really honing their surfaces. As such, he was not a prolific painter. Like a forensic scientist, he also took photographs of his paintings in their various stages. That’s how particular he was about his work.

Marwan was thrilled with the exposure he got in the Arab world, with shows in Beirut, Sharjah and Doha, and since 2007, featuring increasingly in several international institutions such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris, London’s Tate Modern and the British Museum, the Museum of Modern Art Chicago, Serralves Museum in Porto and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh.

But another unquestionable worry he felt was the insufficient recognition and exposure of his work in Germany. He was right.

Despite the Berlinische Galerie Museum of Modern Art extensively acquiring and exhibiting his paintings since the 1960s, it was not until the reopening of the Staedel Museum in Frankfurt in 2012 that a major painting by Marwan was installed alongside one by Baselitz.

That marked the first time in more than 50 years that two paintings by two rivals were placed in one room at a leading German museum. This significant gesture is credited to then-director Max Hollein, now director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Although he did not receive the credit he warranted, many in Germany and beyond acknowledge that Marwan was an excellent painter. His work speaks for itself and is today getting the appreciation it has long deserved.

Remembering the Artist is a monthly series that features artists from the region