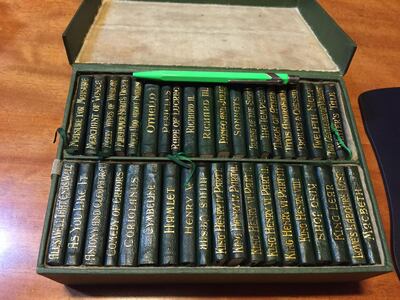

Beautiful volumes of Qurans, exquisitely bound copies of the Bhagavad Gita, tiny thumb-sized Bibles and volumes of Shakespeare's works, measuring no more than three inches in height and width, lie neatly nestled inside cardboard boxes in a dehumidified room, in Siddhartha Mohanty's home in Bhubaneswar, India.

They’re part of his collection of miniature books – a passion that started well over a decade ago.

Mohanty collects only miniature books in English and he claims to have the largest collection in Asia. Sometimes, if the books pertain to an Indian subject in other languages, he likes to acquire them, as he did with Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore's works in Hungarian.

He has miniature antique editions of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, more than 60 copies of the Quran from around the world, and more than 200 copies of the Bible – some with their own small stands – almanacs and children's comics. The oldest book in his collection is an almanac from the 16th century.

"I was attracted to a diminutive copy of the holy Bhagavad Gita in a book shop in Madras [Chennai] in 2003. The finish and binding was perfect and the font was clear, and I bought several copies to give away as gifts. That was the beginning of my love affair with miniature books," Mohanty, 45, tells The National.

An engineer who runs his own family business in mining and steel, Mohanty is currently the only Indian member of the prestigious Miniature Book Society in the US and he has more than 4,200 antique, rare and new miniature books in his collection.

He hopes to start a museum of miniature books in Bhubaneswar and says has asked the government for land for it. "I want everyone to derive pleasure from my fascinating collection," he says.

A book is said to be miniature only if it is three inches or smaller in height, width and thickness, he explains. "Those less than one inch are called micro miniature books and you need a magnifying glass to read them. They are exact replicas of the original books, usually, and if they are abridged versions, it is mentioned in the beginning."

Historically, miniature books started off by being items of convenience or lucky charms, portable curiosities that could be slipped into a lady’s purse, a man’s pocket or attached to his belt, like a psalms or devotional book.

Victorian ladies had miniature books of etiquette that they could refer to discretely. Miniature almanacs were convenient to check dates on the move. And it is said that some mini books were also made for concealment – in countries where religious persecution was common, people of another religion could pull out a miniature prayer book at ease, without being noticed.

Many miniature dictionaries and encyclopaedias were used by storytellers, who would slip them into their pockets to refer to them secretly and impress the audience. It is said that Napoleon always travelled with his miniature book collection of Shakespeare's plays.

In the 13th century they were handwritten and painted, and later they were printed. The 19th century was the golden age for miniature books, when fine printing and binding techniques were used to produce these small masterpieces that required exceptional skill.

They had extravagant bindings of leather, vellum and even sterling silver, and had gilt decoration and etchings. Miniature books also extended to almost every genre.

"India is the only country that makes perfectly functional miniature books that are sold at the cheapest prices," says Mohanty.

However, finding these small tomes is a long process. He used to look for them on his travels, but today, he finds miniature books through online auctions, dealers and sometimes through families who have inherited old volumes.

"Today, there are only about five to six publishers around the world that still publish miniature books. Quite often, I have to back out when I have to compete in online auctions, with big collectors or museums who can naturally offer better prices."

"One of the rarest books that I have in my collection is the Khordeh Avesta, the Zoroastrians’ book of prayers, in Gujarati. I found this in an online auction, and later a Parsi family gave me another copy which belonged to their great grandmother. I also have 28 miniature propaganda booklets the Nazi Party issued, to be bought by common people and the proceeds were used to fund the soldiers’ winter uniforms. These have a tiny string and could be hung on a Christmas tree as an ornament.”

Mohanty now also restores books that are in a poor condition.

“I learnt it from an online course and picked up some pointers from some antiquarian book collectors. I get the conservation materials from the US. Moisture and humidity can damage these delicate books and they have to be handled very carefully, too,” he explains.

He spends several hours after work, repairing damaged books in his collection, taping torn pages restoring covers and reinforcing weak spines.

“Collecting miniature books is a fairly expensive hobby and I feel blessed to have the resources to follow my passion,” he says.

“I follow many leads and trails to collect these miniatures, and though not all materialise into something concrete, they leave me with lovely memories and stories. The journey is as important as the end, after all.”