Manifesta 8

Murcia and Cartagena, Spain

The Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MoCHA) began life as a small gallery, founded in 1973 and funded by the Friends of Puerto Rico, a non-profit initiative in New York. Initially known as the Cayman Gallery and located in a derelict industrial space in SoHo, it was part of a political movement that established alternative spaces for artists who fell outside of mainstream American culture, namely artists from the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and from South and Central America, who had long settled in the United States but were still regarded as second-class citizens in the art scene.

In 1985, after organising more than 500 events (these included political action campaigns as well as shows, concerts and film screenings), Cayman declared itself a museum. It moved into a bigger space on lower Broadway and launched a programme of ambitious, expensive exhibitions that addressed the most controversial issues of the day: Aids, women's reproductive rights, discrimination against minorities, poverty and the widening gap between rich and poor. Both alone and in collaboration with other small, like-minded New York institutions such as the New Museum of Contemporary Art and the Studio Museum of Harlem, MoCHA positioned itself as one of the art world's champions against the conservativism of the Reagan administration.

Just five years later, MoCHA abruptly shut down, in the middle of an exhibition which included work by the then-unknown Gabriel Orozco. Later, the former director said that the museum's collapse was brought about by a sudden 200 per cent rent increase. Curators, however, blamed years of overreach and financial mismanagement as the real reasons.

This story of institutional implosion is the subject of a special six-part exhibition now on view in the southeastern Spanish city of Murcia. The MoCHA archives, including exhibition catalogues, press releases, correspondence, budgets, research materials, a panicked hand-written note from a staffer begging a donor for a quick infusion of cash, and, oddly, a letter from the White House desk of Ronald Reagan himself, commending MoCHA on its success, are now housed in the library of a community college in the Bronx.

They were made public, on written request, in 2004. Thanks to the Alexandria Contemporary Arts Forum (ACAF), the curator Yolanda Riquelme and six local artists who are bringing this fascinating material to life, those archives have now travelled to Spain. There they are serving as an apt repository of cautionary tales for the chaotic and unwieldy biennial extravaganza known as Manifesta.

Just as MoCHA caught a wave of identity politics and institutional critique in New York in the 1980s, Manifesta seized on the fall of the Berlin Wall as an opportunity to explore the relationship between Eastern and Western Europe in the 1990s. It paid particular attention to site specificity and sensitivity to local context. Fault lines and conflict zones have been Manifesta's raison d'être from the beginning, and its catalogues are peppered with catchphrases about borders, refugees, exile and diaspora.

To go by its own rhetoric, Manifesta is a radical reinvention of the biennial format. It mounts an international exhibition of contemporary art every two years, but unlike, say, Venice, it moves around. The first edition took place in Rotterdam, the second in Luxembourg, the third in Ljubljana. It is the only truly itinerant biennial in Europe, and it earned the official title of Visual Arts Ambassador of the European Commission two years ago. This may be less ironic than, for example, guerrilla theatre groups from the anti-Vietnam War era being named cultural emissaries for the US State Department and sent abroad to promote the same government they once hoped to topple (the San Francisco Mime Troupe, for example). Even so, to have become part of the EU's bureaucracy would seem to compromise Manifesta's claims to radicality.

Over time, Manifesta's concern for Europe's east-west axis has given way to interest in the continent's north-south divide, with subsequent editions taking up temporary residence in Italy and the Basque region of Spain. Now, in a move that seems explicitly attuned to headline news stories about immigration and assimilation, minarets and mosques, Manifesta is pushing toward Europe's southernmost border. The current edition, which opened two weeks ago and runs for three months, is taking place in the cities of Murcia and Cartagena. It is conceived, on paper at least, as an event held "in dialogue with North Africa".

Whatever that means, the curators chosen to assemble Manifesta 8 have thankfully ignored it. In its place they offer a loose and easygoing engagement with questions about the Mediterranean, the Levant, the Middle East, the Arab world, Spain's historical encounters with Islam, the African continent both on and below its northern rim, and cultural difference in general. Simply put, they offer the time and space to experience works of art that may be off-topic but which are riveting and challenging nonetheless. The Arab contingent is well represented, North African participation is patchy, and none of this really matters in the end.

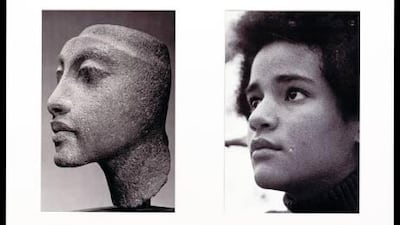

Sherif el Azma's 20-minute video Rice City (2010) plays with the psychoanalytical interpretation of drives and desires, riffs on the conventions of film noir, and is by far the artist's best work to date. Lorraine O'Grady's installation of black and white photographs, Miscegenated Family Album (1994), is a revelation, based on one of her own performance pieces from 1980, and retrieved from a period in art history that passed not so long ago but that still feels timeless and fresh. Ann Veronica Janssens' disorienting room full of dense pink artificial fog is biennial-style spectacle at its best and most irreverent.

Curated by three different groups, ACAF, the Chamber of Public Secrets (CPS) and tranzit.org, Manifesta 8 spreads across 14 venues in two cities some 50 kilometres apart and includes the work of close to 100 artists and collectives. In addition to exploring Europe's contested nooks and crannies, Manifesta has also established itself over the years as a laboratory for curatorial thought. Collectivity is this year's buzzword, which seems a little rich given that ACAF, CPS and tranzit.org worked almost entirely independently of one another. Their contributions are distinct and bounded, marked on the event's map in their own colour-coded blobs. Each group's portion of the show can be taken in as a single unit, rather than as part of an overall utopian design.

Tranzit.org is a solid show with more hits than misses, though too much preliminary rhetoric about how the process of putting it together generated a "Constitution for Temporary Display", presumably some kind of founding document for an imaginary republic of contemporary art. CPS rambles about politics and perception and privileges a certain aesthetic messiness. ACAF tests out its self-styled "Theory of Applied Enigmatics," and in the process, makes Manifesta 8 well worth the long and complicated haul.

ACAF's contribution is basically one project divided into four parts. An exhibition titled Overscore is installed in an old post office in Murcia and a new maritime museum in Cartagena. Prayers for Art is a collaborative piece, for which the astounding New York-based beatboxer Kenny Muhammad translates into sound the mood and tone of a series of short texts written by artists, critics and curators, expressing their hopes and fears about art itself.

Backbench is a streamlined architectural structure that played host to an assembly of speakers over the summer and now serves as a support for an immersive video installation delving into art, activism and institutional co-option. The MoCHA Sessions, reviving the history of the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, is a research project that has been given room to breathe in its own space, where six artists have been invited to produce six exhibitions using the failed museum's archives as material (the current show is organised by the artist Rosell Meseguer).

Instead of providing the dialogue requested by Manifesta's brief (ACAF being the only curatorial group actually from "North Africa), the curators Bassam el Baroni and Jeremy Beaudry initiated one further project, Incubator for a Pan-African Roaming Biennial, which, with a general coordinator and a raft of potential collaborators on board, will think through the process of creating an organisational structure in Africa to match Manifesta in Europe. This seems a more satisfactory option than a one-off conversation that cannot, despite the organisers' best intentions, pass for anything besides an obvious token gesture.

ACAF's Theory of Applied Enigmatics is represented in the catalogue with a graphic that looks like two feedback loops which momentarily converge. It's an ingenious (and depressing) visual element that allows anyone remotely involved in the visual arts to chart their progress from, say, empowerment and the making of meaning, through reflection, analysis, losing focus, outrage, laying blame, scapegoating, denial, disbelief and loss of faith through to despair, cynicism and the dissolution of institutions. This is where ACAF's project overlaps with MoCHA and Manifesta itself. Four years ago, Manifesta nearly imploded under the weight of its own pretension when it tried to mount its sixth edition on either side of the divided island of Cyprus. The event was cancelled only weeks before the opening, amid a sea of acrimony, accusation and promises of legal action.

That was Manifesta's first brush with institutional collapse. It has since recovered but, on the evidence of Murcia, it remains an organisational and logistical mess. Just as identity politics and institutional critique did before, site-specificity and sensitivity to local context have fallen out of favour in the art world of late. To regain its radicality, Manifesta may have to give the token gestures a rest, get out of the cultural diplomacy game, and rediscover its critical footing. Otherwise it may suffer MoCHA's fate, or become yet another bloated, grandstanding biennial like the others.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a staff writer for The Review in Beirut.