A new history of photography in Egypt, Kaelen Wilson-Goldie writes, overcomes a paucity of records to situate the country at the heart of the medium's history. "The commonplaceness of photography, and the radical differences between it and the traditional arts, has made it a refractory problem for theorists, and one that has not submitted with grace to the traditional intellectual apparatus of art historical study," wrote the eminent curator and critic John Szarkowski in his book, Looking at Photographs, published in 1973. "As a rule, photography has not developed in a disciplined and linear manner, but has rather grown like an untended garden."

It is to the writer Maria Golia's credit that her new book, Photography and Egypt, does not even try to jam its subject into an elegant or orderly art-historical narrative. Rather, it traces the development of photography in Egypt over the last 170 years through a chaotic and unruly field of social, political and economic contexts. Golia does not view the medium in isolation, nor does she focus solely on its aesthetic attributes or technological advancements. Instead she considers photography as a dynamic practice whose means and ends cannot be disentangled from the overlapping twists and turns of the country's history.

"A comprehensive history of photography in Egypt," Golia warns, "would be a much heavier book than the one in the reader's hands." Indeed, Photography and Egypt runs just under 200 pages, with five brisk, eminently readable chapters book-ended by an introduction and an epilogue. The structure, as well as the tone, closely follows that of Golia's previous book, Cairo: City of Sand, an intimate portrait of the sprawling megalopolis, which the writer, an American who has spent most of her life abroad, has called home for more than 20 years now. Both books convey a deep and wonderfully complicated affection for Egypt. But Photography and Egypt has a much different purpose: it is not an occasion for personal reflection, but an attempt to carve a space for Egypt at the heart of photography's history.

Szarkowski's Looking at Photographs, like his predecessor Beaumont Newhall's The History of Photography, is inextricably bound to an institutional collection. Both men worked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, directing its highly influential department of photography. Both of their books, alongside their groundbreaking exhibitions, helped to cement photography's place as an art form on par with painting and sculpture.

Unlike Szarkowski, Golia had neither an institution to support her nor a collection to consult. In fact, considering how little she had to work with, it is somewhat remarkable that she even signed up for such a book. There is no dedicated museum or major centre of photography in Egypt (or anywhere else in the region, outside of Iran). Seriously considered exhibitions and publications on the history of photography in Egypt are few. Archival material is far from readily available. One might even question whether or not photography, barely a footnote in the written histories of modern Egyptian art, constitutes a living tradition at all, much less one one with an agreed-upon canon of decisive works.

The Contemporary Image Collective (CIC), an independent, non-profit initiative established six years ago in Cairo, has played an admirable role in generating critical discourse about photography. But it does not have a collection or a conservation mandate. It also strikes a tricky balance between old school, documentary-style photojournalism and more conceptually-minded contemporary art. In past years, CIC's regular festival, Photo Cairo, has feted vintage prints by the city's most beloved studio photographer, the late Levon Boyadjian, otherwise known as Van Leo. More recently, however, Photo Cairo has come down firmly on the side of video and installation. Assessing this shift in the final chapter of her book, Golia, perhaps a bit conservatively, dismisses it as fashion, "a triumph of style over content".

Besides library collections at the American University in Cairo and the American University of Beirut, the only other institution committed to the study and preservation of the region's photographic heritage is the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut. In addition to sourcing images from its substantial collection, Golia briefly discusses the foundation in her epilogue, holding it up as a success story to end her book on a hopeful note.

But the material that allows Golia to build - à la Szarkowski - on the work of these organisations barely covers two of her chapters: one, "Studio Venus", focuses on portrait photographers such as Van Leo in the 1940s and 1950s; the other, "The Show of Shows", delves into the work of contemporary artists such as Maha Maamoun, Hala Elkoussy and Ahmad Hosni, among others. But much of the rest of the book details Golia's experience of confronting, over and over again, a heartbreaking disregard for photography in all its forms.

For example, when she visits the premises of Cairo's Société des Amis de l'Art, which hosted an annual photography salon from the 1930s through the 1950s, the director welcomes her to peruse the archives - which turn out to be a single desk drawer strewn with exhibition catalogues from the 1960s, Ministry of Culture pamphlets from the 1980s and a copy of a Saudi Arabian airline's inflight magazine. When she arrives at Helwan University's Faculty of Applied Arts, she discovers that two weeks earlier, the photography department sold off its vintage equipment, box cameras and all, to a junk dealer. When she calls on the heirs of one of the first Egyptians to master photography, she learns that crates of glass-plate negatives dating back to the 1900s were simply tossed off the family's balcony during a round of home renovations.

Given this dire state of archival affairs, why bother piecing together a shattered history of photography in Egypt at all? Golia makes a fairly convincing argument that Egypt ought to be regarded as, if not the birthplace, then at least the quintessential stomping ground of photography, the ultimate destination for its first generation of practitioners, and a compelling barometer for gauging the pressure of Egypt's past on its present.

The history of photography, she notes, has always been linked to Egypt. It was in 11th-century Cairo, after all, that the Basra-born scientist Ibn al Haytham designed the first camera obscura to illustrate his theories of light's refraction. In 1839, when the astronomer François Arago announced Louis Daguerre's invention of the daguerreotype in France, he cited Napoleon's expedition to Egypt 40 years earlier. "To copy the millions and millions of hieroglyphs covering only the exterior of the great monuments of Thebes, Memphis, Karnak, 20 years and scores of draughtsmen would be required," Arago declared. "With the daguerreotype, a single man could execute this immense task."

At the time, Egypt was under nominal Ottoman administration and boasted a population of just four million people (compared to 80 million today). That same year, the French painter Horace Vernet and his student Frédéric Goupil-Fesquet travelled to Alexandria, where they demonstrated how the daguerreotype worked for the Egyptian pasha Mohammed Ali. Confronted with the first image he had ever seen on a polished silver plate - depicting the outside wall of a building that housed his wives and children - Ali declared photography to be the work of the devil, turned on his heel and walked away. He eventually came around, however, and warmed to the technology to such an extent that he was soon reportedly posing for the camera, and learning to operate it himself to photograph his harem.

For the rest of the century, foreign travellers - including Gustave Le Gray, Maxime Du Camp, Félix Teynard and Francis Frith - flooded into Egypt to photograph ancient monuments and archaeological relics. "Their pioneering work," Golia writes, "mostly featuring Egypt's monuments and picturesquely portrayed inhabitants, helped establish the enduring iconography that Egypt's name evokes." Their imagery also helped Egypt become one of the modern world's first tourist hubs, photographed incessantly in a manner that defined postcard perfection while departing ever-further from reality.

"Histories of photography often concentrate on this period," Golia writes, "stopping short of the time when Egyptians were no longer the subject of photographs", but the authors of them. In many ways, the driving ambition of Photography and Egypt is to identify the moments when Egyptians appropriated the technology for themselves. Photography matters in Egypt not only because it has informed how the world sees the country - and how Egyptians see themselves - but also because it has played such a strong but stealthy role in calibrating the course of the country's history.

Starting in the early 20th century, for example, the Egyptian press began using photographs to illustrate newspapers and magazines. Among the most popular subjects were the royals - the descendants of Mohammed Ali, who came to be known first as sultans, then as kings, during the years of British occupation. Most of the earliest court photographers had been foreign-born, but their apprentices were often local. In print, members of that second generation found a new market for their work.

Moreover, as equipment became lighter and technology cheaper, these up-and-coming photographers were able to follow the royals around when they left their palaces. Not only did this contribute to the creation of celebrity journalism, it also, somewhat accidentally, transformed devotional court photography into potentially divisive reportage. Out in the world, photographers such as Mohammed al Ghazouli - whom Golia pegs as the first Egyptian photojournalist - looked beyond the royals to find protests, demonstrations and angry crowds agitating for independence. Ghazouli may have closely followed the outings of King Fuad, but he also photographed the public appearances of the monarch's archrival Saad Zaghloul, the nationalist leader whose popularity surged, circa 1919, thanks to the sudden ubiquity of his image.

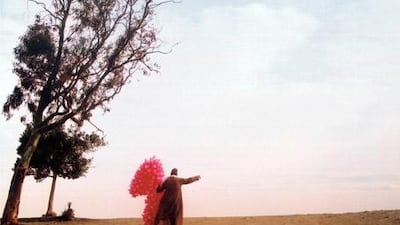

Two decades later, a group of artists grappled with photography's political potential. The collective, known as Art and Freedom, was essentially a multinational, Cairo-based offshoot of the surrealist movement in France. Art and Freedom issued manifestos, published magazines and railed against nationalism, fascism and notions of the Arab "fatherland". Its members also made great photographs (rare and increasingly hard to find), such as Iqbal Henein's portrait of her husband George draped across a sand-strewn train track bed. George Henein had befriended André Breton in Paris, and founded Art and Freedom with the painter Ramses Yunan. For this group, photography was a means of not only escaping but also effectively destroying both academic and folkloric art. History, however, was not on Art and Freedom's side. Like many other members (and patrons) of the collective, Henein left Egypt, never to return, after the revolution in 1952 - a notably inopportune moment to subject nationalism to ridicule. The new regime found a great many uses for folkloric art, and considered image-making a part of its propaganda machine. Anyway, with Nasser's rise, photography had found itself another king.

For the most part, Art and Freedom, like surrealism in the Arab world more generally, has been written out of the region's art history. It is one of the subtle and sensitive triumphs of Golia's book that she rustles it up as a temptation to future researchers.

Kaelen Wilson-Goldie is a staff writer for The Review in Beirut.