Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language, which was published in 1755, was the first comprehensive English dictionary ever published. When looking inside it, you can see that the word 'east' is defined by the British writer as "the quarter when the sun rises".

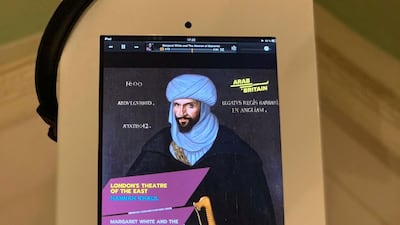

In London's Theatre of the East, a new exhibition at the late writer's house in central London, four artists explore different aspects of British-Arab culture. Although the reign of Queen Elizabeth I is well taught in British schools, it is less known that at that time, the British had strong ties with the Ottoman Empire, as the UK tried to distinguish itself from many of its European neighbours. Through the four floors of the Grade I-listed building, which dates back to the end of the 17th century, four artists tell stories of Arabia's (covering the Middle East, North Africa and Turkey/Constantinople) influence on British culture through the mediums of playwriting, fashion and trade. The exhibition runs between Friday, November 8 and Saturday, February 15.

The artists began working on the exhibition by having a ‘research day’ with three academics to explore the influence of Arab culture on British culture.

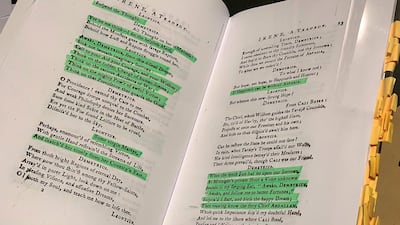

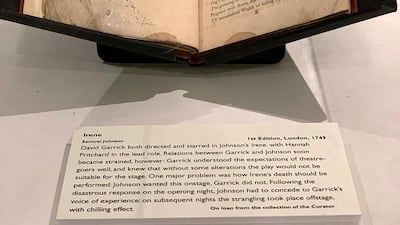

"It featured an overview of Irene – Johnson's only play, which contains a host of Turkish characters, 'Mohommedans' – and some problematic attitudes towards them," says one of the artists, Hannah Khahil. "The play is a starting point for my and the other project artists' creative responses."

For her part of the exhibition, Khahil made a dramatic monologue based on the first publishing of the Quran in 17th-century Britain, which at the time proved controversial. Through an eight-minute recording, she tells an emotive story of the wife who has to run a print factory after her husband dies, professing her love to the Quran, but expressing her sorrow after the first copy of it to be printed in Britain was burned. It was later reprinted with a warning introduction and epilogue, and that was the copy that went on sale in 1649.

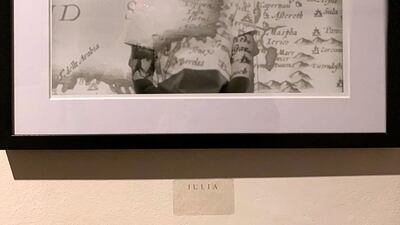

On the top floor of Johnson’s house, there are a selection of photos and stories from young British-Arab women. There are two sets of photos: the first contains serious pictures of them in black and white juxtaposed against a map of their home country, the women's facial expressions matching their stories of family, migration, conflict and identity. These stories are next to the set second of photos, which are more personal to the women.

One woman tells the story of her family, who fled Lebanon as refugees during its civil war and another woman, who is Egyptian, says that she always feels at conflict with her identity and that her friends from her homeland joke that she is “British”.

"I come from a very mixed background, too, and yet I was raised in the British education system," Lena Nassana, the artist behind the photo exhibition, tells The National. "I was born in Cairo, but had my university education here, I've always felt this very fluid sense of identity and depending where I was it would change.

"When you're at home you don't question it because everything is taken for granted but when you leave, you no longer feel comfortable. You get uncomfortable and you start questioning why that is."