Tagreed Darghouth has never made art to please. Instead, she uses it to confront. Born in Saida, Lebanon, in 1979, the painter has spent the past decade creating an unsettling series that holds up a mirror to society's most disturbing traits and deliberately shines a spotlight on issues that many people would rather ignore.

Since 2008, she has held four solo exhibitions at Agial Art Gallery in Beirut. The first, Mirror Mirror, reflected on the increasing number of Lebanese women who were choosing to have plastic surgery. Fair and Lovely focused on the African and Asian domestic workers who raise children, cook and clean for families who overlook and undervalue their contributions.

In recent years, Darghouth’s focus has expanded beyond the borders of Lebanon to encompass global issues. Her last two exhibitions explored the atomic bomb, featuring eerie paintings of mushroom clouds, skulls and the craters left in the Navada desert by nuclear weapons testing, which has transformed the landscape into a deformed, pockmarked wasteland resembling the surface of the Moon. For Darghouth, these exhibitions are all related. “Every subject gives me a visual challenge to work on. It’s a matter of choosing an object that makes the work variable and rich,” she explains. “I think it’s like I’m telling a story with each subject as a chapter of the work.”

Analogy to Human Life, which opened at Saleh Barakat Gallery – Agial Art Gallery's newer, more spacious sister venue – last week, is Darghouth's biggest and most ambitious exhibition to date. The culmination of two years of work, it features more than 100 paintings, ranging in size from 20cm to three metres across. In these works, Darghouth explores systematic violence, focusing on the Israeli occupation of Palestine, to provoke broader reflection on what she sees as a global epidemic.

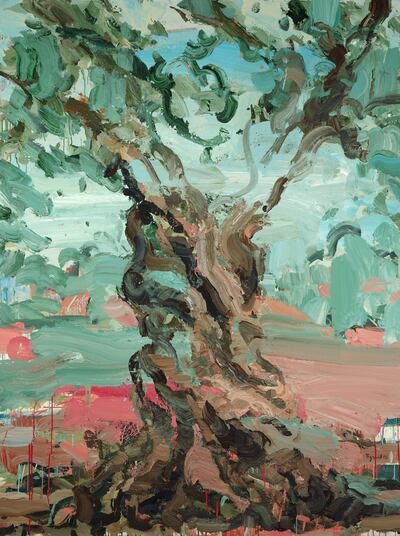

In keeping with her research-driven approach, the work stems from diverse influences including 17th century Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn, 19th century Post-Impressionist painter Vincent van Gogh and Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek. The result is pastoral paintings of lush olive trees paired with images evoking destruction, violence and occupation, including hydraulic excavators, meat-grinders, tanks, fighter planes, skulls and slabs of raw meat.

Zizek’s writing about the Palestinian concept of “al-sumoud” – steadfastness or resistance – turned her down another path. “He was explaining that it has nothing to do with religion or with politics but it’s part of their identity as Palestinians,” she says. “I read an article where he was saying that the Israelis tried, during a period of peace, to systematically destroy the olive trees and he was referring to the concept of al-sumoud.”

While looking deeper into the history and symbolism of the olive tree, Darghouth came across van Gogh’s series of 18 paintings of olive trees, created in 1889 and 1890 while he was living in an asylum in France. “I actually chose the title of the exhibition based on his observation,” she says. “He was saying that the olive tree resembles the human life cycle and he thinks that the most divine moment is when people harvest the olive tree: it’s a moment of connection with God.”

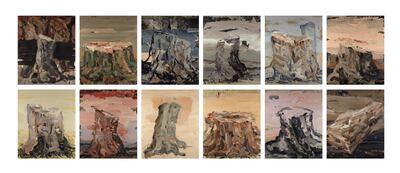

Building on Zizek’s writing and the long history of the olive tree as symbolic of the Palestinian cause, Darghouth extrapolates from van Gogh’s evocation of the tree as an analogy for the natural life cycle. Paintings capturing the gnarled trunks of olive trees that have been felled, leaving only stumps, confront viewers with the idea of lives cut short and the reality that some lives are deemed less valuable than others.

The paintings of tree stumps are particularly moving in contrast with Darghouth’s paintings of flourishing trees, topped with canopies of silvery leaves. These works recall van Gogh’s description of the olive trees of Provence. “They are old silver, sometimes with more blue in them, sometimes greenish, bronzed, fading white above a soil which is yellow, pink, violet tinted orange,” he wrote to his brother, adding that the “rustle of the olive grove has something very secret in it, and immensely old. It is too beautiful for us to dare to paint it or to be able to imagine it”.

It is the contrast between the beauty of Darghouth’s living olive trees and the menace of the other paintings in the show that creates a jarring reflection on violence. In the context of the olive tree as a symbol of life and death, Darghouth decided to return to the subject of meat. A wall of paintings captures slabs of bloody red flesh, while two larger works show hunks of meat hanging from S-shaped butcher’s hooks.

Darghouth has offset the visceral pinks and reds of her meat paintings with shades of mint and sky blue, softening the violence of the images while also evoking the colours of her olive trees in a way that draws disturbing links between the subjects. She also scrutinises the tools of violence, picking out meat mincers in shades of olive green and brown and painting an F-16 fighter plane atop a bloody red backdrop that evokes the glow of flame but is in fact the remnants of one of her earlier studies of raw meat.

The most striking and obvious symbols of violence are the skulls that are becoming Darghouth’s signature, having also featured in her work on nuclear weapons. Evoking classical memento mori paintings, they help to convey the universality of her message by evoking death as the great equaliser. “It’s something to remind others, to remind myself, and I think it’s related to the environment I live in. We’ve never had peace. We’re always conscious that something might go wrong, and the skull will always be the thread that holds my exhibitions together,” she says.

She is uncompromising about her work’s capacity to unsettle. “It’s a bit unexpected to work on meat or skulls. People want something more joyful and more colourful and I’m not willing to do that,” she says. “I’m not willing to do that because somebody should always point out what’s going on and I think my job as an artist is to take an aesthetic approach while saying what I want to say – what I think needs to be said.”

Analogy to Human Life is on show at Saleh Barakat Gallery in Beirut until October 27

_______________________

Read more:

UAE memorial artist Idris Khan on the 'overwhelming' nature of making award-winning Wahat Al Karama

Louvre Abu Dhabi’s new exhibition: Japanese and French cultures explored side by side

From humble beginnings: this Palestinian museum in the US has big ambitions

_______________________