The aspirational parents of Cairo's Pyramids Plateau are many, and private tutor Hisham Orabi aims to reach as many of them as possible. Not only is Orabi an Arabic language expert and a consultant for an Egyptian newspaper, Al Wafd, he is nothing short of a history legend. Or so he says.

In other highly competitive markets the tutor might have employed a website, social media or print publications to get his message across. But operating, as Orabi does, in one of Cairo’s working class neighbourhoods, he resorts to a medium that captures the attention in ways that combine authentic, street-smart modernity with far older traditions.

Painted on walls, Orabi's advertisements are composed of khatt – hand-rendered Arabic calligraphy, written by none other than the Bronze Inventor, a group of some of contemporary Cairo's most distinctive calligraphy artists, named for their distinctive use of metallic and glitter-based paints. The team consists of five brothers who work as a collective using their surname, Eleiwa.

The Bronze Inventor's calligraphy style is unmistakable, thanks not only to their use of metallic and glitter paints, but also to materials that are becoming increasingly common among Cairo's street calligraphers, which the eldest Eleiwa brother, 30-year-old Mohamed, insists he pioneered with the group in 2014. "We were the ones who came up with this idea to use bronze in our banners to attract more attention. After we had applied this approach on a wide scale, many others started to imitate us and to claim that it was their idea," the street artist says in an interview with graphic designer Ahmad Hammoud, founder of Samaklaban, an organisation dedicated to documenting and celebrating Cairo's vernacular visual culture and popular design. "That's why it was crucial to include our signature on every banner, to claim the title of the real 'Bronze Inventor'. Had no one tried to steal it, we wouldn't have put so much emphasis on it."

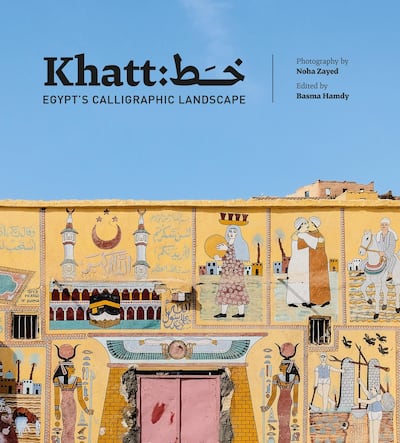

The interview appears in a new book, Khatt: Egypt's Calligraphic Landscape, which surveys the continued use of hand-painted typography and calligraphy throughout Egypt in a series of essays and interviews, including one with French-Tunisian calligrapher eL Seed, a resident of Dubai whose 2016 mural, Perception, spreads across the facades of almost 50 buildings in the Coptic Manshiyat Nasir neighbourhood on Cairo's outskirts. Written by various authors and edited by Basma Hamdy, a graphic designer and associate professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, Qatar, the book's chapters cover the use of khatt on trucks, boats and shops, in Hajj paintings – executed on the walls of the houses of those who have undertaken the Hajj as evidence of their piety – on shrines, cinemas and everyday consumer objects.

'Perception' by eL Seed:

Ranging from amateur scrawls on walls to fading advertisements, roadside greetings, prayers and graffiti-style set pieces, the widespread and popular use of khatt transforms the surfaces of Egypt’s urban landscape into a kaleidoscopic, multilayered text that merits close reading.

Thanks to the photographs taken by Noha Zayed, the Cairo photographer behind the "Arabic Typography" Instagram account that currently commands more than 100,000 followers, Khatt: Egypt's Calligraphic Landscape manages to turn what could be an obscure and academic subject into a sumptuous guide to a phenomenon that is simultaneously popular and increasingly under threat.

Hamdy discusses the contemporary use of khatt in an essay that explores the history of the practise, tracing its origins back to the ancient use of hieroglyphics and the emergence of architectural calligraphic friezes that became increasingly popular in Egypt during the time of the Fatimid and Ayyubid dynasties.

For Hamdy, one of the key moments in the history of Arabic calligraphy in Egypt was the foundation, in 1922, of the Royal School of Calligraphy in Cairo under the patronage of King Fouad I. The opening coincided with a period of increased nationalism following a revolution against British colonial rule in 1918 to 1919 and the unilateral declaration of Egyptian independence that was issued by the British government in February 1922. It was a time, Hamdy writes, when "artists and writers, in pursuit of a national identity that rejected foreign occupation, extracted iconic forms from their visual heritage to represent what it meant to be truly Egyptian."

Not for the first time, calligraphy came to the service of the state while also expressing popular notions of national pride and identity, a tendency that was to repeat itself throughout much of the 20th century. During the nationalist period associated with Gamal Abdul Nasser’s presidency, calligraphers helped satisfy renewed demand for products that reflected Egypt’s new-found, post-imperial identity and were commissioned regularly to hand-render book and magazine titles, newspaper headlines, signs, posters and advertisements, some of which can still be seen on the facades of older buildings.

“Travelling through the streets of Egypt, one cannot escape the overpowering role of language in the urban landscape. Words and phrases adorn buildings, vehicles, shopfronts and advertisements,” Hamdy writes. “Layers of time have rendered Egypt an urban palimpsest, where computer-generated fonts compete with traditional calligraphy and experimental lettering.”

Despite the increasing popularity of digitally designed type and a decline in the demand for hand-drawn lettering, 12,000 calligraphers graduate from Egypt’s 390 calligraphy schools annually, including Mohamed Eleiwa, who chose to study at an Arabic calligraphy institute for four years after he completed his university studies.

________________

Read more

Egypt's elusive nomadic Bishara tribe and their Gabal Elba home

Inside the dhows of Abu Dhabi's Mina Zayed

Fadi Kattan: The Palestinian chef dishing gourmet cuisine under occupation

________________

“Long before I joined the institute, I noticed that I had a talent in calligraphy. But I wanted to upgrade my skills, learn the basics of Arabic calligraphy and move beyond being an amateur,” he tells Hammoud. “In order for you to present decent work, you must follow the rules of calligraphy. If you do so, passers-by on the street will realise that you are well aware of what you’re doing. Nonetheless, the talent is a gift from God – it’s the foundation; refinement follows.”

Despite the increasing use of digital technology, Hamdy believes that there is a particular quality to handwritten text that will always distinguish it.

“There is a nostalgia associated with handwritten lettering that can never be replaced with a digital alternative. A nostalgia that is potent in urban Egypt,” she writes romantically.

“You can see it in the faces of the people on the street, smell it in the hustle and bustle of the traffic, hear it in the sound of car horns and street vendors, and read it in the words that adorn everything you see, words that weave the rich and complex tapestry that is Egypt.”

Khatt: Egypt’s Calligraphic Landscape by Saqi Books London is available now