What's curious about Crude, the Jameel Arts Centre's inaugural exhibition, and the subject of a symposium on Saturday, is how it takes something ostensibly hegemonic and frames it as something postcolonial.

What could be more powerful than oil, the substance that fuels cars, produces plastic and has lifted this region to economic heights?

But Murtaza Vali, a Sharjah-raised curator who has conducted lengthy research into the cultural history of the substance, also reveals a side of crude oil that has been little noted – the decades of immigration, expat children, temporary Gulf stays and unforeseen political consequences that accompany the development of oil across the region.

An exhibition about oil

"Oil resists representation," Vali tells The National at the opening of the show, which inaugurates the new Jameel Arts Centre, a non-profit institution that was established on Dubai Creek by the Saudi family foundation Art Jameel.

Vali means that in two ways. Firstly, that the slippery substance of oil is rarely depicted in art, and a lot of his research was simply to map where and when it appeared, and secondly, the history of oil is little represented from the standpoint of oil-producing nations.

The result is a strong, well-thought-out show, which moves chronologically from Iraq during the 1950s, via Latif Al Ani's photographs, to oil's current effect in shaping the Arab Gulf economies, via work by the late Hassan Sharif, Lantian Xie and the GCC collective. It has good pacing in terms of variety of works and the modes of engagement it demands of the viewer, and is particularly strong in its middle section, where it looks at oil not as a timeless geological substance, but as a historically and geographically specific discovery.

The work on display

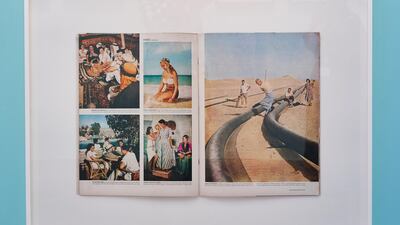

Artist Raja'a Khalid, who works in Dubai, shows Desert Golf (2014), a series of media images showing expats from the Arabian-American Oil Company (later known as Aramco) playing golf in the sand, with oil flares rising behind them. One image from the cover of Fortune magazine shows two men wearing only shorts and caps, one of them intently putting a red ball on the grassless golf course that the company built for its employees. Across from this work is Manal Al Dowayan's If I Forget You, Don't Forget Me (2012), a series that includes a video of interviews with some of the men who worked in oil companies at the time.

In The ARD: A Study for a Portrait 1-28 (2018), a documentary presentation by Hajra Waheed – a commission for Crude by the Jameel – the artist looks into the history of the Aramco department the Arabian Research Division (ARD). The ARD helped supply information about the region to the company's strategic division, basing its analysis on onesided and ill-informed stereotypes of Arabs that were drawn up by a scientist in the US, and which are still in use today. She collages documents of the ARD and illuminating documentation of the period, although the presentation of this work suffers from one of the pitfalls of documentary artwork, as many of its key insights remain hidden from the viewer.

Other works underscore an intimacy with the subject, such as a series of images isolating oil flares, also by Waheed, that Vali says "turn something that is often seen as a byproduct of war into a thing of beauty". Monira Al Qadiri also shows her masterpiece of a video, Behind The Sun (2014), in which she overlays Sufi poetry on to Kuwaiti state TV footage of oil fields set alight in 1991.

The motivations behind the exhibition

For all these artists, oil is not an idle subject. Al Dowayan and Waheed grew up on the Aramco compound in Dhahran in eastern Saudi Arabia; Khalid grew up in the Kingdom as well; and Al Qadiri is from Kuwait. This is an exhibition about oil, but also about the histories of a generation who grew up in its wake – the trailing, migrants, the GCC residents given a boost.

Vali has been an important figure in the Dubai art scene for some time, and one of his principle contributions was to interrogate the make-up of artists and histories in the UAE. This exhibition closely examines oil as a subject with remarkable, protean powers, but it also continues the work that Vali has done in the realm of artistic representation.

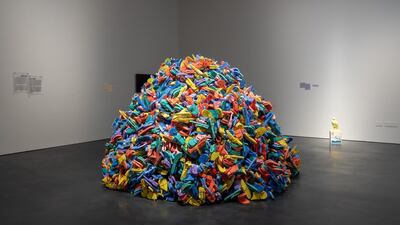

The symposium on Saturday will extend the work of the exhibition further, bringing out strands in the curation that are related to current theoretical debates, as well as looking at fiction as another cultural realm where oil appears. Recent debates in art-making have focused on the "material turn", which Vali elaborates here via the items of material culture that shed light on the past. The golf balls, the workers' slippers, the meeting documents that might be buried in the sand – these tell a different story than what is put out by governments and even academia, and often help to bring less important segments of society into view.

A second motivation behind the exhibition links it to discourses that are known as "new materialism" – which is a way to understand objects as having an agency that exists irrespective of humans. The classic example here is the relationship between an orange and a knife that cuts it, and oil, as a form of transmuted energy, is a prime subject for this inquiry.

What to expect at the symposium

The symposium will take in other examples of artistic projects that looked at energy sources, such as Cuauhtemoc Medina's project for the roving European biennial Manifesta 9 in 2012, The Deep Of The Modern, which examined the relationship between coal mining and modernisation. Jeff Diamanti, a scholar from the Netherlands, will analyse Christo and Jeanne-Claude's use of oil barrels, such as the proposed 1977 project for Abu Dhabi that Christo is still pushing through. Graeme Macdonald, from the University of Warwick, will debate "petrofiction" with NYUAD lecturer Deepak Unnikrishnan, whose work Temporary People also gives voice to the experience of long-term migrants in the Gulf region.

The Jameel event is the closing chapter for the exhibition, and Dubai will miss these 50 historical works and commissions. Few other exhibitions have taken such a direct, sympathetic approach to recent history as actually lived around us.

Crude will run at Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, until Saturday. For more information about the show go to www.jameelartscentre.org