When creative minds and hearts come together, they can produce unforgettable works. Though these famous artist couples did not all collaborate with one another, they undeniably influenced each other's practices. We look at the stories of some of the art world's most well-known couples, from the 20th century up to our contemporary times.

Marina Abramovic and Ulay

The story of Marina Abramovic and Ulay's break-up eclipses almost everything else they created in their 12-year relationship. The pair met in 1976 and produced a number of performance artworks that challenged the limits of the body and explored ideas of artistic identity. Then, in 1988, they performed the work The Lovers, for which they trekked for 90 days from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China – covering a distance of 5,995 kilometres in total – and then met in the middle to end their relationship.

When the couple planned the journey years before, their original intention was to marry once they reunited. The ordeal was captured by the BBC in a documentary, which followed Abramovic as she set off from the Yellow Sea and Ulay from the Gobi desert.

After the break-up, the two did not speak to each other for more than two decades. In 2010, their brief reunion shocked the art world once again and sparked a video that went viral. It was not a rekindling of romance, but rather an unexpected visit from Ulay during Abramovic's endurance performance, The Artist is Present, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. For eight hours a day, Abramovic would sit in a chair and gaze into the eyes of any visitor who sat across from her. She teared up at the sight of Ulay.

The relationship seemed to sour again in 2015, when Ulay filed a lawsuit against Abramovic over royalties and attribution on their collaborative works. However, both artists reportedly settled their differences on the occasion of Abramovic's first major European retrospective at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark in 2017.

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

Two of Mexico's most important artists from the 20th century, Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera shared a complex and tumultuous relationship that involved fights, extramarital affairs, and a divorce and remarriage within a year.

Rivera was not only a painter, but also an activist who used his art to shine a light on politics and workers' rights in Mexico. He was drawn to Kahlo after seeing her art in 1928, and the two began a relationship soon after. They were first married in 1929. Kahlo's 1931 double portrait of herself and her husband offers a glimpse into their relationship at the time, with the couple possessing distant stares and seemingly in the midst of letting each other's hands go.

A master of the self-portrait, Kahlo revealed much of her personal tragedies, internal life and emotions on the canvas. In one painting titled Diego and I (1949), Kahlo sheds a tear while an image of Rivera with a third eye sits on her forehead. It seems to place her husband as a source of wisdom inextricably linked to her own state of mind.

Despite their 20-year age difference, the couple stayed together until Kahlo's death in 1954 – they divorced in 1940, and remarried in the same year. Rivera described her death as "the most tragic day of my life". He died three years later, in 1957.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Marie Denat, better known as Christo and Jeanne-Claude, produced a number of remarkable environmental and installation artworks throughout their relationship.

The two met in the late 1950s when Bulgarian-born Christo was in Paris, struggling to make a living by painting portraits, and was commissioned to work on one by Jeanne-Claude's mother. The pair married in 1962 and remained together until Jeanne-Claude's death in 2009.

Using everyday materials such as plastic and fabric, the duo made their name through the practice of wrapping and draping historical buildings such as the Pont Neuf in Paris (1985) and the Reichstag in Berlin (1995). One of their most ambitious projects was the 1983 Surrounding Islands, where they covered the shores of 11 islands in Florida with pink plastic.

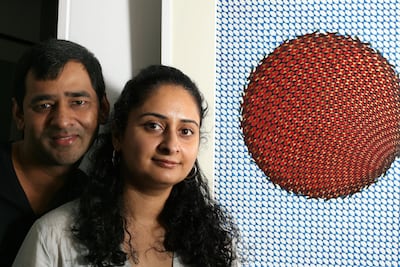

Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid

Having trained in miniature painting at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Imran Qureshi and Aisha Khalid maintain individual artistic practices that have transformed the traditional form of painting into contemporary art.

While both employ floral motifs in their work, Qureshi adds elements that speak of violence in modern-day Pakistan. He often uses red paint to evoke blood, contrasted with delicate renderings of petals. Khalid explores these issues in her own way, employing the image of a flower that cannot grow, to symbolise grief. Her visuals are particularly influenced by the 2014 terrorist attack at the Army Public School in Peshawar, which killed 150 children.

Khalid recently participated in Al Burda Endowment Programme, where she presented her textile installation The Garden of Love is Green Without Limit during last year's Abu Dhabi Art. It will also be on show at next month's Al Burda Festival in Dubai. The piece recalls the Kaaba in the way the tapestries are hung to form a cube. Its intricate patterns refer to Persian carpets, and have been created with the use of thousands of push pins, creating tension in the work.

Qureshi has also shown in the UAE, being commissioned for Abu Dhabi Art's Beyond: Al Ain programme in 2018. He developed a site-specific work at Al Ain Oasis, where he painted the waterways and aflaj irrigation systems in ways that considered death, life and rebirth.

The two artists continue to live in Lahore, and they have two children.

Idris Khan and Annie Morris

The story of Idris Khan and Annie Morris involves a whirlwind romance. The two were introduced by a mutual friend, and three months later, they were engaged. Though their practices are distinctive from one another – Khan's work being more minimalist and monochromatic, Morris's more playful sculpture and collage – they have presented an exhibition together in Mumbai's Galerie Isa.

Morris was born in London and studied at a variety of art schools in the UK and France. Inventive with her combinations of colour and material, she is best known for her cast bronze sculptures of stacked colourful orbs. In 2006, she was commissioned by Burberry creative director Christopher Bailey to design a couture gown made of hand-painted clothes pins.

Khan, whose father is from Pakistan and mother from Wales, studied at the Royal College of Art. He has acknowledged the influence of Islamic prayer in his practice, specifically the ritual of praying five times a day. This has translated into the artist embedding patterns and repetitions into his works. He was commissioned to design Abu Dhabi's Wahat Al Karama or "Oasis of Dignity", a memorial to Emiratis who have sacrificed their lives in service to their country. They married in 2009, have two children and share a studio in north-east London.