This year was already meant to be the final year for the Green Papaya Art Projects. Manila’s oldest artist-run nonprofit was planning to permanently close its physical space in 2021 and had been working for years to digitise its archive of previous projects in order to preserve its history online.

Then, on the morning of Wednesday, June 3, a fire tore through the two-storey apartment which houses the art space in the neighbourhood of Kamuning, Quezon City. The ground floor ceiling collapsed. Upstairs, much of Green Papaya’s archives were burned and damaged. No injuries were reported, but three other businesses in the surrounding area were also ravaged by the blaze, the cause of which was deemed by firefighters as electrical.

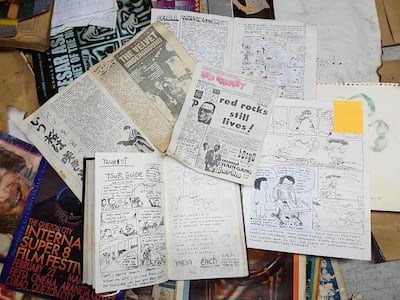

The team has since moved most of the salvaged materials to the residence of the nonprofit’s co-founder, artist Norberto Roldan. Among its archival material are 300 works donated by artists and a small library of books.

In the fire’s aftermath, Green Papaya’s closing plans have been upended or seemingly hastened. The nonprofit not only faces irreparable damage, but also the erasure of decades of work as it scrambles to save what remains of its archive.

The history of the art space

Roldan established the art space in 2000 with dancer and choreographer Donna Miranda. “One of the reasons we decided to open Green Papaya is because there was a need for a space for people to experiment and figure out how to proceed with their practice. The idea was to provide a space for young, emerging artists who were looking for a halfway platform between university and the mainstream scene,” he says.

“We were interested in looking at new practices by younger generations. Before then, we had just been through decades of social realism in the Philippines, from the 1970s to the 1990s. It was pretty much the predominant practice,” he adds.

Roldan's work is a departure from the figurative style of social realism, preferring assemblage and found objects as his material. He is a prominent artist in his own right, with a work included in the Guggenheim Museum’s collection.

He and Miranda set up a curatorial team, involving artists and designers to organise shows. Over the years, Green Papaya’s programming grew, mounting exhibitions that would travel abroad, including to the UK and Australia, establishing residencies for artists and forging artist collaborations in the US and around the world.

It remained modest in terms of space and operated on a “hand-to-mouth existence”, as Miranda once described in an online post. In 2002, it moved to a converted garage in an area known as Teachers’ Village. “When we opened, we were very particular about the kind of community we wanted to nourish. We were very near the University of the Philippines, so our community composed of faculty from the College of Fine Arts and students from the university,” Roldan says.

In 2008, Green Papaya relocated again. This time to an apartment built in the 1940s in Kamuning, which became its exhibition and performance space until the fire broke out. The fate of the building is now uncertain. “There are only two options, either the building will be demolished, which will be a total loss, or it will be conserved, which will require a lot of money,” Roldan says.

The challenges of keeping the space afloat

Over the years, Green Papaya has overcome numerous difficulties to stay afloat, surviving despite scant government funding. In 2010, the art space was invited to attend No Soul for Sale at London's Tate Modern, an art event held in the Turbine Hall that featured independently-run art spaces and artist collectives.

The Philippines’ National Commission of Culture and the Arts (NCCA) denied Green Papaya’s request for funding, as it determined the show was not included in a so-called ‘list of prestigious international events’. “Our community came to our rescue,” says Roldan. “We self-funded and bought our own tickets to London.”

There were other challenges too. Manila’s art scene was beginning to shift. An art market was blossoming, with galleries cropping up in pockets of the commercial district of Makati and the arrival of Art Fair Philippines in 2013. “We started in period when the art market in Manila was not developed. Then sometime in 2007, the artists coming out of universities were being grabbed by commercial galleries, so the purpose of the ‘halfway spaces’ have been rendered irrelevant,” he says.

The decline of art spaces such as Green Papaya spells tragedy for artistic communities, especially in the Philippines, where institutional support has been largely absent. These spaces offer artists a platform and much-needed room to experiment, to meet with other practitioners and to expand their ideas without the pressure or expectation of financial return.

“I’m not saying that every artist should struggle before they are able to get to the mainstream, but they won’t get to experience a lot of things that are essential for an artist to develop. They won’t go through the rigor of exploring. I think what is lost is a sense of community, which is very important for artists. Green Papaya has been trying to establish a community where people can have open discussions with artists and colleagues, not just people from the same disciplines,” Roldan explains.

'The timeline has changed'

For now, Green Papaya turns its attention to a greater threat, as its archival material remains vulnerable. Saved from the fire site, the team now face another problem: water damage from the rain. With the monsoon season coming in, Roldan’s residence is not an ideal storage place – there isn’t enough space and pools of water collect in the area.

After the incident, donations have rushed in from the artistic community to help Green Papaya navigate its next steps. “We consider ourselves under the radar… We don’t consider ourselves part of the mainstream art scene. Surprisingly, expressions of support keep pouring in,” says Roldan.

“The priority now is finding another space where we can move everything that can be retrieved from the fire site and make sure that our volunteers get compensation. We also want to operate the space with a staff and team for the next 18 to 24 months,” he adds.

“We need a dry location,” adds Merv Espina, Green Papaya’s programming director who stays in the same residence. “Just get the materials somewhere secure. The idea is to have [Green] Papaya’s afterlife online, but how to get there from this point … the timeline has changed. It is more urgent to fight the elements,” he says.

Archiving will take time, especially with limited resources. As of now, the nonprofit has only one archivist on staff. “The truth of the matter is, there’s not enough manpower and technical expertise to finish everything,” says Espina, explaining that the variety of materials are fragile and require special equipment to scan. These include oversized items and analog media, such as 16mm and 8mm films and VHS tapes.

The donations they receive will help in efforts to preserve the artistic output that Green Papaya has fostered over the years, though how far they will stretch is yet to be seen. Still, Roldan says he feels "humbled" by the influx of support. "If not for this community, we would not have been able to survive this tragedy nor could we have lasted for 20 years," he says.

More information on Green Papaya can be found on their Facebook page.